Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

When people die, families gather—for comfort, to say goodbye, and to tie up loose ends. Loved ones of our deceased ancestors would meet for the reading of the will and to divide up the departed person’s belongings.

Today, genealogists can read all about that process in probate paperwork. These records are often packed with relatives’ names, relationships and residences. They offer intimate glimpses into family love, loyalties and sometimes feuds. You often can fi nd dates of birth, marriage and death, and clues to family migrations and household composition. You may even learn the contents of the family home, barn, closets and pantry.

Probate records can be daunting to find and use. Originals may be buried in remote courthouses or unknown archives. Different counties’ records are organized differently. Thick files, packed with paperwork of all shapes and sizes, may not have been microfilmed, indexed or digitized (though that’s beginning to change). Documents key to understanding the estate may be filed in several places. Unidentified documents, unfamiliar terminology and apparent omissions of loved ones or property may puzzle you.

This workbook introduces family historians to US estate records. By the end, you’ll know what they are, who may be named in them, why they’re worth finding and where to look for them. Better yet, you’ll be ready to start interpreting what these records really say about your family past.

The Probate Process

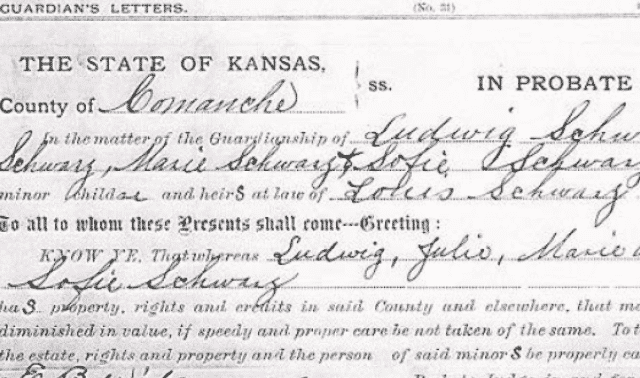

Two major categories of probate records are of interest to genealogists: estates (with or without wills) and guardianships (for minors and “incompetents”). This guide focuses mostly on estate records.

Not everyone left estate records. Some people avoided having their estates probated by distributing assets before they died. Others didn’t own enough to make the estate worth probating. And before the mid-1800s or so, married women often didn’t have the right to dispose of family property by will. (More on that below.)

Estate files were probated either when the deceased left a valid will, or the estate for a person who didn’t leave a will met a minimum value defi ned by local law. A person who left a will was a testator. The executor named in the will executed its terms in a testate proceeding. If the deceased was intestate—he left no valid will—the court appointed an administrator to divide the estate according to inheritance laws in an intestate proceeding or administration.

A lot of people were involved in the probating of an estate. First were the deceased and heirs. Then there were those who did the settling: the executor or administrator, witnesses, surety (see No. 6 below), appraisers and court offi cials who oversaw that everything was done in order.

Anyone who brought claims against the estate could be listed. And in slave-owning families, enslaved people were also named as property to be distributed.

Here’s an outline of the probate process and the paperwork it generated:

- A family member and/or the executor requested that the court open probate proceedings, either by formal petition or a verbal request noted in court minutes.

- The will, if one existed, was brought to the courthouse to be proved at a hearing (notice of this hearing may have appeared in the newspaper). Witnesses testifi ed that the will was written as stated and that the deceased was of sound mind and not under constraint. If the will wasn’t witnessed, two people who knew the deceased’s handwriting authenticated it. Those wishing to contest the will presented their grounds.

- After the will was proved, the court issued letters testamentary, authorizing an executor. The executor had to be named in the will and approved by the court.

- If the will didn’t name an executor or there was no will, the court authorized an administrator by issuing letters of administration. Surviving spouses may have had the first right to administer the estate. Elderly spouses and women often declined and requested that a younger male relative handle it.

- The court appointed guardians for heirs who were minors or legally incompetent. A guardian could be appointed as a steward of such a person’s property or over the person, or both. Men were usually made guardians over minors’ estates, even when a custodial mother was still living. If the father was alive but the child received assets independently (such as from the deceased mother’s family), a financial guardian might be appointed. Older children, usually at least age 14, often were allowed to choose a guardian. Guardianship appointments, bonds and accounts often identify relationships between parents, children and other relatives.

- In some cases, a relative or friend posted surety. This was a bond comparable to the value of the estate as surety against mishandling by an executor, administrator or guardian. A surety bond sometimes states the relationship of the person who posted it to the testator.

- Three reputable people not otherwise involved in the estate inventoried and appraised all property that belonged to the testator. Inventories were very specific, often down to the number of pillowcases and spoons.

- Public notice was posted and/or published in the newspaper that the estate was to be probated. This served as notice to creditors, who could fi le claims against the estate.

- The executor or administrator began settling accounts to pay creditors. Anything owed to the deceased was collected. All these generated receipts, which may be in the probate file.

- Personal property (or “moveable estate”) and real estate not being given to heirs was sold at public auction. Court orders were sometimes also required for these auctions, and bills of sale resulted.

- Settlement was often a lengthy process. Meanwhile, monies were paid out to support widows and minors. Expenses incurred by the executor or administrator were reimbursed. The widow’s dower right was set aside so creditors couldn’t claim it.

- During the probate process, the court documented changes in family status, such as if heirs moved, died or married. Courts also may have taken interim accountings of the estate, especially in complicated, lengthy cases, or those involving highly valued estates.

- Before the case was closed, one last published notice gave interested parties a chance to make a claim.

- When all heirs were in agreement, and sometimes once minor heirs reached 21, the estate was settled. The final settlement may appear in a separate document or in court notes.

- The estate was distributed according to the will and the law, including any laws specific to inheritance rights of widows and oldest sons (see “Understanding probate records”). In intestate proceedings, certain “priority” relatives were named heirs-at-law. All heirs signed receipts.

Finding estate records

You’ll look first for evidence of the above events in estate packets—master files generated during the probate process. Original documents should be there: the will, letters of administration or testamentary, bonds, claims, interim accounts, receipts, a final settlement statement and more. In addition, the court often kept separate transcripts of records, though procedures changed frequently. The clerk may have transcribed estate documents right into the daily minutes of the court. Or transcripts of wills, inventories, bonds, letters testamentary or letters of administration also may be in separate books.

Don’t forget to track down other probate-related documents, too. For example, you might find guardianship documents if someone was appointed to watch over an heir’s assets. Deeds for property sold by the estate should be recorded with other deeds. (Land transferred or “devised” in a will wasn’t necessarily recorded. But look for the next sale of that property with the heir as seller.)

Many probate records are still with the county courts that originally created them. These courts may be called probate, orphan’s, surrogate, chancery, district or circuit courts. Note that jurisdictions can change over time, and the records may have been moved to a court that currently handles probate. Confi rm the location of probate records from your ancestors’ era by calling county government offices or checking online. Locate county government offices by using The Family Tree Source Book.

In some states, county courts forward older records to the state archives; the Toolkit box lists probate research guides for several states. Find out if this is the case for your ancestral county from the county clerk, online searches or a local genealogy guide.

Colonial-era estates fell under the jurisdiction of colonial governments and the oversight of the mother country. Look for these first in US state archives, which may at least have copies (for example, New Mexico has probates from the Spanish colonial period on microfilm). These may also be published or indexed, as are many British Colonial wills. See FamilySearch and Wills and Probate Records [UK]: A Guide for Family Historians by Karen Grannum (The National Archives UK).

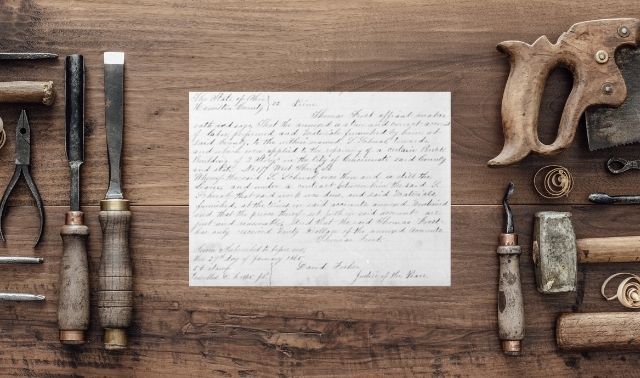

It’s most effective to research probate records at the courthouse, if you can make the trip and the records are still there. You may be able to search on-site indexes that aren’t available online or on microfilm. Original estate files are worth reading in person. Each folded, tattered scrap of paper (handle them carefully) may hold new family information. And when you’re at the courthouse, it’s much easier to track down related documents scattered in other court files.

Some probate records and wills are online. FamilySearch hosts collections of probate records from counties in more than 30 states. Many aren’t yet searchable by name, so you’ll need to browse index volumes (if they’re available), then use the information in the index to find the record you need. To find these collections, go to FamilySearch and use the filters on the left to narrow the list to probate and court collections from the state you need.

Ancestry.com has searchable probate-related collections (such as published indexes and extracts) from all 50 states. FamilySearch and Ancestry.com plan to digitally publish 140 million US wills and probate images from 1800 to 1930, so you should see more online soon. Scattered collections are at Mocavo, RootsWeb, USGenWeb, and various state or county websites (see the links at Cyndi’s List). Or search on the county and state name plus the word probate, estate or wills in your web browser.

Many wills and abstracts of estate records have been published and/or microfilmed. Search by location (usually county-level) in the FamilySearch online catalog of books and microfilms, and look for a Probate Records category. You can rent microfilmed records through your nearest FamilySearch Center. Also search WorldCat, which shows libraries that have copies you can request through interlibrary loan. Don’t rely on indexes or transcriptions except as finding aids: Follow them to original sources.

Understanding estate records

Finding estate records is exciting. There’s nothing like seeing an ancestor’s handwritten will, learning the contents of her kitchen and finding a list of all her children and their spouses’ names. Yet it’s easy to misinterpret what you see or to miss important clues.

Understanding the laws of the day is essential. Certain heirs took precedence or had automatic privileges. Distribution of assets to some heirs may not have been part of the probate process. Terminology we think we know may have had a different meaning. Remember these guiding principles:

Some heirs counted more than others

Women had few financial rights until states began to pass women’s property laws in the mid-1800s. Single women were often the most independent, though they may have had guardians appointed to manage their assets. A married woman’s husband legally controlled her, including her earnings (this was called the law of coverture). A man often granted his widow only a life interest in property that would revert to other heirs upon her death. A widow had automatic claim to a third to half of her husband’s estate (known as dower right). If the will gave her something different, she could choose which to accept.

Watch for language in the will that describes whether she inherited property outright (free to dispose of her assets as she wished) or only a life interest, or whether she would lose her assets upon remarrying. These stipulations may explain her choices when settling the estate.

Early inheritance laws favored oldest sons. Colonial laws of primogeniture awarded them landed estates automatically and in full. Primogeniture wasn’t recognized in New England, and Rhode Island had a variation on the law that granted double portions to oldest sons. Fortunately for everyone but firstborn sons, the new US government quickly outlawed primogeniture.

Everyone mentioned is important, but not everyone who is important is mentioned

A will might not bother to mention an oldest son when primogeniture was in effect, since that process was automatic. Consider that possibility for a will before the early 1800s. Other kin may go unnamed, too. Wills didn’t have to name every close relative, just those to whom a specific bequest was made. Sometimes the heirs weren’t even named, just described as “each of my living children.” Some relatives received their share of the estate before the testator’s death. Aging adults often signed over the bulk of their fortunes during their lifetime in exchange for elder care.

Look beyond the list of heirs for your relatives. Witnesses, executors, administrators, guardians and others involved in an estate were usually friends or close relatives, just as they are today. Those who bought items from the estate also may have a personal connection (especially loved ones trying to reclaim a widow’s own belongings for her).

Some potential family connections may be harder to verify and some may be red herrings. Enslaved individuals may be undocumented biological relatives of the slave-owning family. Also, major creditors often participated in the probate process to protect their rights. Creditors often weren’t related. Try to ascertain each person’s relationship to your family.

Language can mislead

Relationships described in wills, a boon to genealogists, might have different meanings today. A “cousin” might just mean “kin” (or even a really close friend). “In-laws” may also refer to step-relationships (a “brother-in-law” may actually mean a stepbrother). Additionally, the term “orphan” could refer to a minor child who lost even one parent (especially a father). Minors are also called infants, but this just meant underage, not necessarily newborn. Keep things clear by transcribing documents exactly. That way, as you learn more, you’ll better interpret the intended meaning.

Look for clues everywhere

You may be disappointed to learn an ancestor died without a will. But intestate cases can be telling. All qualifying heirs had to be identified. You might find names and residences of a surviving spouse, sons, daughters (with married names) and even grandchildren who inherited in a deceased’s parent’s stead. In the absence of a living spouse and children, the deceased’s siblings, parents or other relatives may be listed.

Probate records may contain clues about other records you should check, too. A bequest to the local Congregational church means you should look for the deceased’s membership and donation records. Mention in a household inventory of special tools or supplies may hint at an occupation, which may lead you to search professional license applications, regional or trade histories, labor or trade newspapers, city directories and more.

Finally, many of the above clues require a working knowledge of probate law, which varied by state and time period. Start with detailed discussions of probate in genealogical guides. Look for published histories of state laws in WorldCat. (Search the category “Probate law and practice” for the state in question.) State Statutes: A Historical Archive is a database from Hein Online that you can search at major research libraries. Refer to a resource such as Black’s Law Dictionary (especially historical editions, available at law libraries). Or ask at a law library for help identifying the most current probate statutes, which cite previous laws. Trace them backward until you get to the right time period.

The Parts of a Will

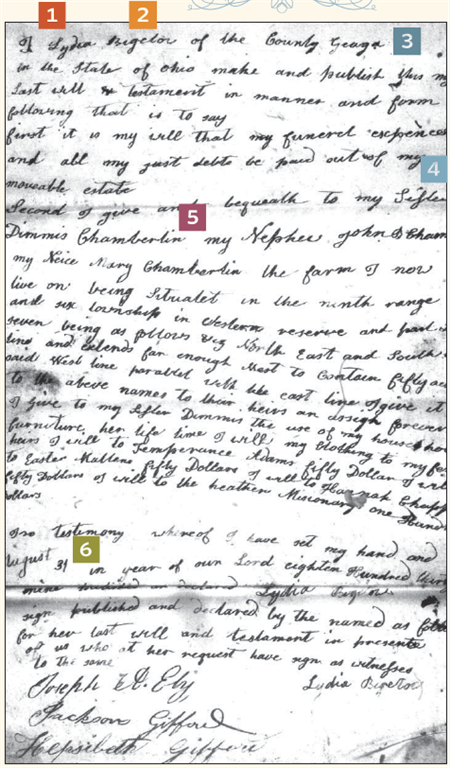

1. For testate cases, the will is in the estate packet. Also search for the transcribed copy in court records and compare the two.

2. In most states, a woman owning and willing real estate during this time period is a clue she was single when she wrote the will.

3. The testator’s real estate is in the same county where the will is filed, meaning the deceased lived and died there. Look for more family records in this county.

4. Willing her real estate and personal property to a sister, niece and nephew indicates she probably had no living children when she died. Look for confirmation in other sources.

5. Wills may name a relative and specify the family relationship, such as “my sister Dimmis Chamberlin” or may simply say “my heirs.”

6. Narrow the range for the death date: it’s between the date of the will and the date of the initial request to initiate probate proceedings.

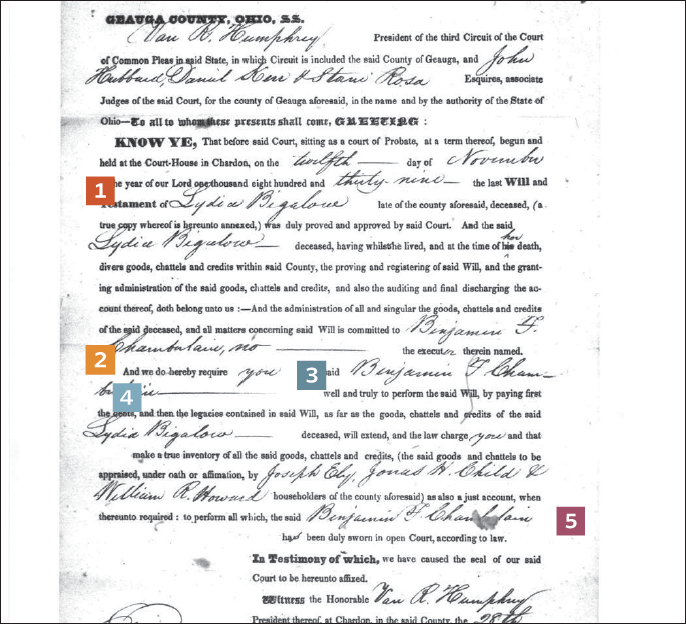

The Parts of Letters of Administration

1. Note the reference to a will, which has been proved.

2. Look for a petition in the estate packet asking for the appointment of an administrator. In this case, the petition identified Chamberlain as Lydia’s nephew and Dimmis’ son.

3. Lydia’s will doesn’t name an executor; the clerk forgot to cross out the word the. The court transcript of the letter confirms this. This authority to proceed with the estate is a letter of administration and Benjamin Chamberlain is an administrator, not an executor.

4. Here are details of the duties of the administrator, which indicate paperwork to be generated.

5. Benjamin Chamberlain filed the “just account,” or final settlement, required of him 30 years later—showing how long the probate process can take.

A version of this article appeared in the September 2014 issue of Family Tree Magazine.