Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Our ancestors would have been amazed at the hoopla surrounding the public unveiling of the 1940 census in 2012, following the expiration of the 72-year privacy period. Back in 1940, after all, they had more exciting things going on—good and bad—than the census: war in Europe, the lingering Great Depression, a presidential election.

Today, that enumeration opens a window into your family’s history. In addition to genealogical clues, you’ll learn how many weeks your parents or grandparents worked the prior year, how much rent they paid, what the family’s income was and more. The census asked everyone 34 questions, and asked another 15 questions of a random 5 percent of the population whose names fell on lines 14 and 29 of each sheet. You can learn more about how the 1940 census differed from previous censuses here.

For the first few months after the release of the 1940 census, finding your ancestors was quite a project. Lacking an index, you had to search the 3.8 million images by place-based “enumeration district” (ED for short). Thankfully for those of us with less patience, indexes have been created by FamilySearch, Ancestry.com and MyHeritage.

You can also search the FamilySearch indexes free at participating partner sites (links to 1940 census resources): Archives.com and Findmypast. ProQuest, another partner in the project, will include the 1940 index in its HeritageQuest databases for libraries. Both indexes link to digitized images of the original enumeration forms, and you may need to register for a free account on the site you choose to search.

All of this makes finding your ancestors in the 1940 census a snap—most of the time. In fact, with only a few clicks at FamilySearch.org, entering only first and last name (it helps to have an odd surname), I found my father enumerated in the census—not once, but twice. He was counted not only at his first job, teaching at what’s now New Mexico State University in Las Cruces, but also with his parents back in Moline, Ill.

Not all 1940 census searches prove so productive, however; I ran into a brick wall when I tried searching for my mother’s grandfather. Let’s use the five steps I tried to solve the mystery of my missing great-grandfather to help you map the course of finding yours.

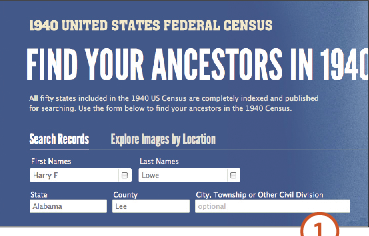

1. Run a basic search

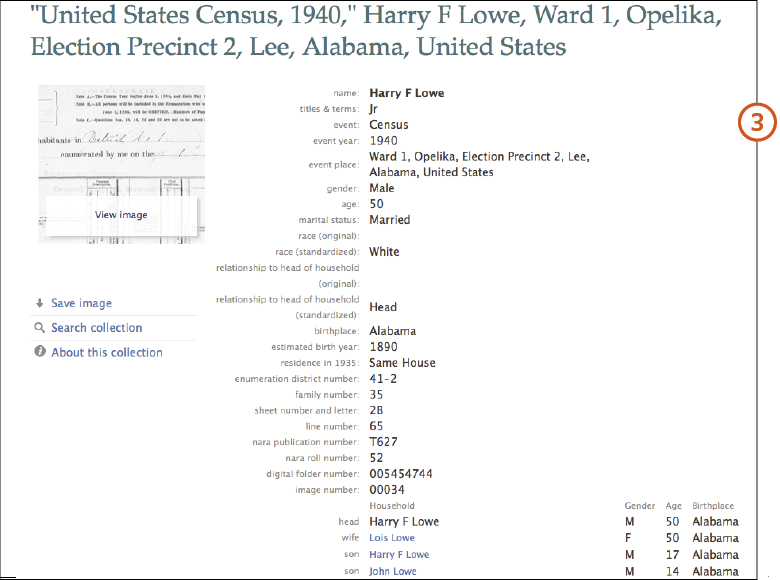

I started my search for Harry F. Lowe, a resident of Lee County, Ala., at the time of the 1940 census, with Family-Search.org. You can use any of the 1940 census websites mentioned above. In fact, if you come up empty on one of the FamilySearch partner sites, try another site’s index to see if you have better luck there. Plug in at least a first and last name, and unless you’re searching for an unusual surname, narrow by state and county if you can. FamilySearch lets you enter middle initials or names in the First Name box, so I typed Harry F.

This basic search quickly returned a couple of Harry F. Lowes—neither matching my great-grandfather, who was born in 1866. These had to be his son and grandson, born about 1890 and 1923. Keep in mind that the census asked not for the birth year but for a person’s age as of April 1, 1940, so the dates that appear in census indexes are computed and thus approximate. Harry Jr. was actually born in October 1889.

If you’ve found a wealth of hits, you’ll want to try narrowing your search rather than wading through all of them. On FamilySearch.org, you can type in the fields under Refine Your Search on the left to narrow by birth year, residence in 1935 (one of the 1940 questions), gender, race and relationship to the head of household.

But I had the opposite problem—my Harry F. Lowe seemed to be AWOL from the 1940 census.

2. Try spelling variants

I tried the same basic search in Ancestry.com’s index, with similarly perplexing results. In genealogy, though, if at first you don’t succeed, try again with different spellings. FamilySearch.org is actually pretty good at anticipating these, so my search for Harry F. Low (no e) returned the same results. Ditto for Harry Low, no middle initial. Often people went by only their initials, so I reversed course and searched for H.F.—no results at all, either for Low or Lowe.

Over on Ancestry.com, I tried again using search wildcards to catch odd spellings and make sure I wasn’t missing anything. An asterisk can stand in for any number of characters, while a question mark takes the place of a single missing letter. A search on Harry Low* found some people named Harry Lowery, but not my great-grandfather. (Unfortunately, Ancestry.com won’t allow a wildcard search such as L*e. Names must contain at least three non-wildcard characters.) I scrolled way down in my list of the results anyway, as sometimes results you want appear after less-plausible matches.

3. Look for other household members

When you can’t find someone in a census, whether it’s 1940 or earlier, you often can sneak up on the missing entry by searching for a relative instead—someone either in the same household (ideally) or in a (hopefully) neighboring household. For a married couple, it’s simplest to start with the spouse. My Harry F. Lowe married a woman with an unusual name, Nisba Uptegrove Stowe—which is ordinarily a godsend for census searching. But alas, searching for Nisba in any variation (including spelling variants and with and without her maiden name) drew a complete blank.

The next logical attempt would be to search for children, and FamilySearch.org already had found Junior for me. Clicking on his name brought up a full listing for this Lowe household, from which I could also jump to view the actual census page. I scrolled down the household enumeration in hopes of finding Junior’s father living with the family (after all, Harry Senior was in his mid-70s by now). There was wife Lois, son Harry III (again), son John and sister-in-law Josie Fletcher—no Senior.

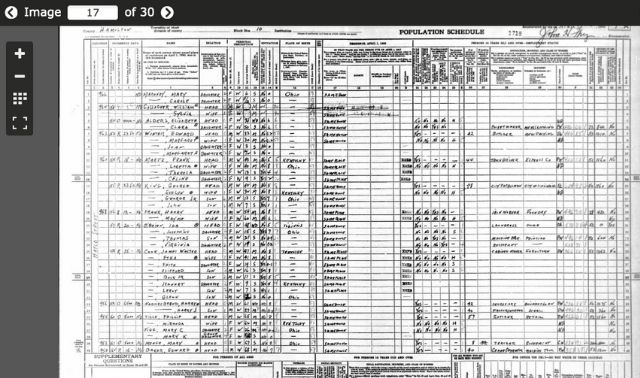

Next I clicked on View Image to see the actual census schedule. Maybe Senior was living next door to Junior and I could find him on the same page. (You’d be surprised how often census mysteries are solved with this simple trick.) Although the image confirms that this is indeed Harry Junior, with “Jr.” written in beside his name in what looks like the census taker’s afterthought, there’s still no sign of his father in the neighborhood.

4. Search for other relatives

When such straightforward family searches fail, it’s time to broaden the circle of relatives and start being methodical. Work your way through searching for the person’s other known children, in-laws, siblings and even cousins who might share a household or at least a census page with your missing ancestor. I knew Harry F. Lowe had a daughter, Louise, who might have been living with him or nearby in 1940. But Louise—whom I grew up knowing as “Aunt Ease”—was actually born India Louise after one of her mother Nisba’s sisters, and she was married twice. Who was she married to, if anyone, in 1940? And what would her name have been in the census? These complications made her a less-than-ideal search candidate.

Aunt Ease’s younger brother, with the promisingly unusual name Oglesby Ashley Lowe, seemed worth a try, but Family-Search.org failed to find him in Alabama. I tried a search on Ancestry.com without any geographical parameters and found him—unhelpfully living in Davidson County, Tenn. I still made sure his father wasn’t hiding in the household, then moved on.

Sometimes the obvious approach is the best. The only offspring of Harry F. Lowe I hadn’t yet searched for in the 1940 census was my grandmother, his daughter. Her name was Bernice, but (again with the unusual names in this family) I grew up thinking of her as “Bumpie”—apparently one of my cousins couldn’t pronounce Bernice, and his version stuck. Because I knew she was married by 1940, the safest bet was to search for her husband (my grandfather), Henry Kline Dickinson.

FamilySearch.org found him right away when I searched for Henry Dickinson in Lee County, Ala. Sure enough, there was his wife Bernice (not as Bumpie), along with my mom and her three siblings. I clicked to view the image, thinking this might be my last shot at finding Henry F. Lowe Sr.

Sure enough, listed in the household right above my grandfather was my great-grandfather—with daughter Louise (last name Tollison, a widow in 1940) and wife “Uptie” (no wonder my search for Nisba Uptegrove Lowe had failed). The circled X by her name indicated that Uptie was the one who’d answered the enumerator’s questions.

5. Process the results

Why hadn’t I been able to find Harry F. Lowe in the first place? That answer took a bit of retroactive searching. I typed Louise Tollison into FamilySearch.org. Finally, the right household popped up, and the mystery was clarified: Harry and Uptie had both been transcribed as Lame instead of Lowe. Ancestry.com’s index had made the same mistake.

What next, now that I’d finally found my great-grandfather? I printed the transcription of his household and the census image, which I also saved to my computer. On Ancestry.com, I added the saved image to my Shoebox for ready retrieval.

Next, I transcribed all the information from the household, as well as my grandfather’s household next door, into my genealogy software. I created a new source for the 1940 census and attached the image. I also added a note about the indexing as “Harry F. Lame” in case I ever need to find this entry again—and to help researchers I might share my file with.

If my search had turned up any real surprises, next I’d start pursuing those details—tracking down other collateral relatives, for example, or birth and marriage records. If I’d still failed to find Harry Senior, I’d search for a death record sometime after the 1930 census in which I’d previously located him. I’ll also go back and retrieve my great-uncle Oglesby Ashley Lowe’s information from Tennessee, and add to my records about his family.

Finally, I went onto Ancestry.com and clicked View/Add Alternate Info, where I entered the correct “Lowe” information and explained how I knew, citing both my family connection and the 1930 census. Maybe future genealogists can be spared a few of the steps I had to go through.

Your 1940 census project might be as simple as finding my father (twice) or as convoluted as my hunt for Harry F. Lowe Sr. However many steps or twists and turns it takes, you’ll find the results rewarding and come away with a new sheaf of answers for your family tree.

A version of this article appeared in the January/February 2013 issue of Family Tree Magazine.