Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

I’ve been researching my third-great-uncle Henry Thoss, hoping to find clues to what happened to his mother, my third-great-grandmother. She disappeared without a trace sometime between Henry’s birth in May 1894 and the 1900 census.

I didn’t find those clues (yet), but I did teach myself a lesson about using census records.

It wasn’t hard to find Henry in Ancestry.com‘s 1940 census with wife Eleanor, 16-year-old stepson William Garcia, and mother-in-law Mary Dietrich.

So Eleanor’s maiden name was Dietrich. It always feels like a win when a woman’s maiden name just presents itself to you like that. And she had a son when she married Henry.

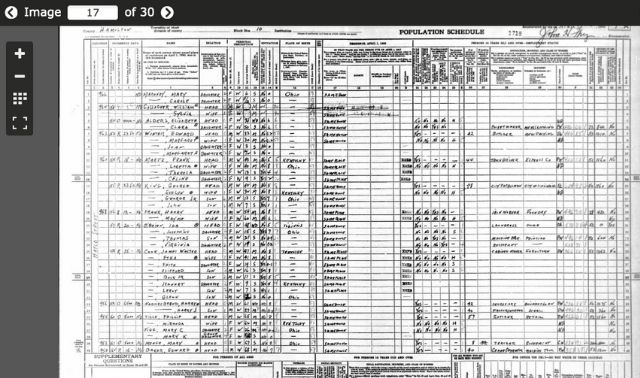

I might’ve added Eleanor Dietrich, mother Mary and son William Garcia to my tree and called it a day. But luckily, I had a little more time to spend, so I went back further. Here’s Henry in 1930:

The household included wife Alma and mother-in-law Mary Dietrich. I’ve seen worse name discrepancies in the census than Alma to Eleanor, and William could’ve been living with his dad in 1930.

Then I noticed what you’re probably already wondering about: Henry’s wife aged an extra six years between 1930 and 1940. Age inconsistencies from census to census aren’t unusual, but six years is a lot. That plus the name difference aroused suspicion.

Looking for Alma, I found a 1932 burial record in a local cemetery. The deceased’s residence matched the censuses, her parents’ last name was Dietrich, and she was the wife of Henry Thoss:

That totally changes Henry’s part of the family tree. After his wife Alma died, her mother, Mary, stayed in the couple’s home. She lived with Henry even after he married another woman, Eleanor, who had a son from a previous relationship.

Looking at the situation with modern eyes colored my assumptions: It’s hard to imagine a mother-in-law remaining with her deceased daughter’s husband, especially after he remarries. Mary died in 1942, according to the Ohio death record I found on FamilySearch.org, which names Mrs. Henry Thoss as the informant.

Another easy census assumption is that a wife is the birth mother of every child in the household who shares the family’s surname. Those children could be the husband’s from a former marriage.

Censuses are supposed to be basic genealogy, right? But based on my initial assumption, I almost gave Eleanor the wrong identity and overlooked Alma. Even if a mistake for a third-great-uncle’s wife wouldn’t have a huge impact on my research, it could mislead someone else, and it’s an injustice to the memory of two women.