Jump to a subtopic:

Finding elusive ancestors in the census

Census enumeration districts

Accuracy in the census

Census records of the 1800s

Other census questions

Finding elusive ancestors in the census

Jump to a question:

Q: My Irish grandparents immigrated in 1921 with my father and uncle. The problem is, I can’t find them in any census. Any ideas?

Q: I found a relative in the 1940 census but I lose track of her after that. Until the 1950 census is released, where can I look?

Q: I cannot find my mother’s oldest sister, born 1893, in the 1920 US census in New York. I’ve searched for name variants and for the households of her parents and ex-husband. Any suggestions?

Q: My Irish grandparents immigrated in 1921 with my father and uncle. The problem is, I can’t find them in any census. Any ideas?

A: It’s frustrating when ancestors go “missing” in one US census, let alone two. Timing further complicates your challenge, as your family just missed the 1920 enumeration. Until the release of the 1950 census in 2022, you have only two years—1930 and 1940—in which to look.

Your first step should be to search for spelling variants. While tales of names being changed at Ellis Island are apocryphal, census enumerators did take liberties with spelling, as did our ancestors themselves. You can speed up and expand your search for spelling variants by using wildcards: When searching either the 1930 or 1940 censuses online at Ancestry.com, FamilySearch or Findmypast, substitute ? for any single character and * for any number of characters (including zero). For example, Brenn?n would find Brennan as well as Brennen, Brennin, and so on; while Brenn* would also find Brennigan and simply Brenn.

Also try a super-wide search at Ancestry.com, leaving one or both name fields blank and filling in what you do know: your relative’s birth year, Ireland as the birth place, and immigration year (for the 1930 census). Note that Ancestry.com has the 1940 census free to search and offers a good variety of search fields, even if you’re not a subscriber. If you’re overwhelmed by the results, try adding part of either name, possibly with wildcards.

If either son reached adulthood by 1940, he may be listed on his own that year. Peruse adjacent pages to see if the rest of the family lived nearby.

If your ancestors settled in a state that took its own census between federal counts, its 1925 and 1935 enumerations are worth a try. States taking 1925 censuses are Iowa, Kansas, New York, North Dakota and South Dakota. Florida, Rhode Island and South Dakota took 1935 censuses.

Finally, the era you’re searching was the heyday of city directories in many places. Check large genealogy websites and local libraries. Often you can find “missing” ancestors in directories, with enough residence information to reveal them in the census—browsing by address, if necessary.

Answer provided by David A. Fryxell

Q: I found a relative in the 1940 census but I lose track of her after that. Until the 1950 census is released, where can I look?

A: City directories, predecessors of the telephone book, can be a valuable resource for finding more- recent ancestors. Check the listings at Online Historical Directories and the collections at Distant Cousin and Ancestry.com. You can also search for city directory at the Internet Archive. If you’re near the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., it has an unmatched collection of microfilmed directories .

Newspapers are another route to information on 20th-century kin. You can search newspaper titles at the subscription sites GenealogyBank and Newspapers.com (where some papers published after the 1923 copyright “cutoff” date require an additional fee to view).

Don’t forget school records, yearbooks and other directories, including old phone books. Ancestry.com has a two-volume database of US public records spanning 1950 to 1993 at and .

It’s also always worth checking to see if a recent relative has died. The Social Security Death Index, available on FamilySearch and other sites, makes it easy. If searching for a married female relative, remember to search all these resources by her married name.

Answer provided by David A. Fryxell

Q: I cannot find my mother’s oldest sister, born 1893, in the 1920 US census in New York. I’ve searched for name variants and for the households of her parents and ex-husband. Any suggestions?

A: There’s little more frustrating in genealogy research than an ancestor who seems to be “hiding” in the census. It sounds as though you’ve already tried some creative searching, but here are a few more strategies that might find her:

Search using wild cards such as * or ?. An asterisk usually substitutes for any number of letters, and a ? stands in for one letter. How and whether these work depends on the site, though, so look for help menu instructions.

Try a different site, which may have transcribed the census differently and may search differently. For example, if you’ve been using Ancestry.com, try FamilySearch.

Since you have a birth year, try searching for anyone in New York with your ancestor’s first name who was born in that year (also the previous and following years). Slogging through the results may be laborious, but you’ll eliminate any surname glitches that could be “hiding” her.

Still striking out? You could also try the 1920 and 1920/21 New York City directories, available via the Family History Library (film numbers 1606141-42 and 1404089-90) and online (1920) at the subscription website Fold3.

Even if you can’t track down your aunt in 1920, you might be able to find her in the 1925 New York state census, which also is searchable on FamilySearch.org. That in turn might give you the clues you need to solve your lingering 1920 mystery.

Answer provided by David A. Fryxell

A version of this article appeared in the December 2015 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Census enumeration districts

Jump to a question:

Q: What’s an enumeration district?

Q: I know we’re years away from accessing 1950 census data, but is there a way to see the 1950 enumeration district maps now?

Q: What’s an enumeration district?

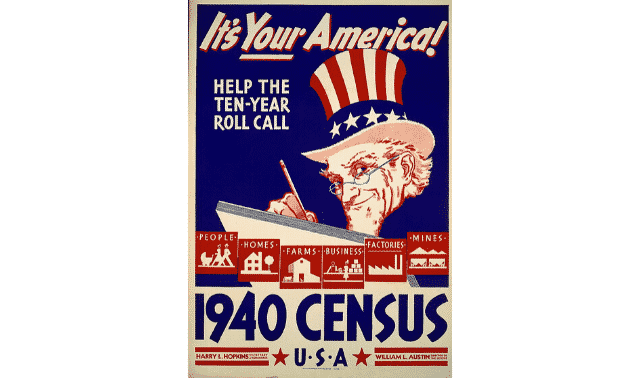

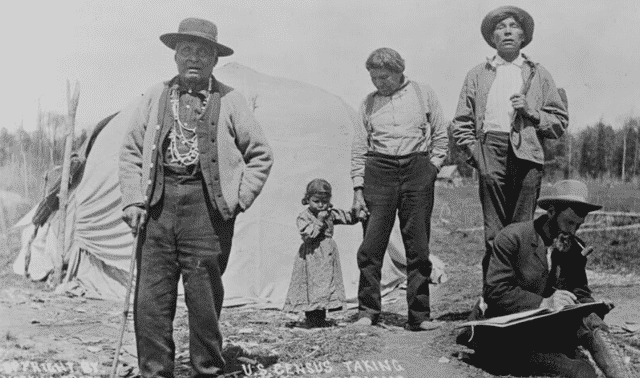

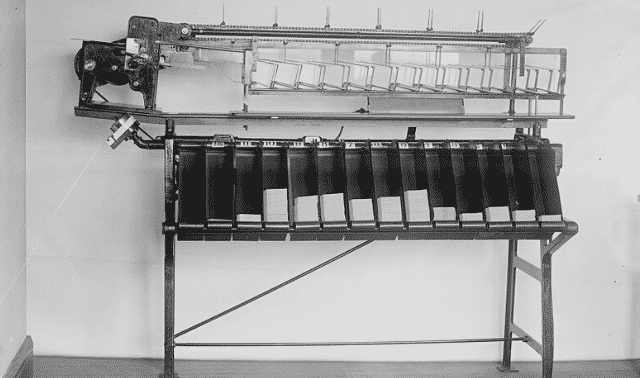

A: An enumeration district (ED for short) is an administrative division of a particular county or township for the purposes of census-taking. Each census taker would be assigned one or more EDs, each of which was designated with a number.

At one time, to find your ancestor’s census return, you’d have to identify which roll of census microfilm contained the right ED. Now that US censuses have been indexed by name, people don’t have to identify EDs the way they used to.

But you may find EDs handy for a few reasons:

If you can’t find a household in records for a database site such as Ancestry.com , you can browse by ED (in Ancestry.com, choose a census year, then scroll below the search box to pick a state, county or township; a ward; then an ED).

Enumerators didn’t always proceed through their EDs in orderly fashion: Rather than go down one side of the street and up the other, they might cross back and forth or double back to places where no one was home. But you can compare a census return to a map of the corresponding ED to plot the neighborhood and see who lived next to your relatives.

To identify your ancestor’s enumeration district, you’ll need to know the state, city and street name, and possibly a street number. Then, try these tools:

Stephen P. Morse’s website has ED finding tools for the 1900 to 1940 censuses. Start by reading this overview to see which ED-finding tool you need (the 1940 tutorial quiz asks you a series of questions that will lead you to the ancestor’s ED). Morse’s site also offers tools for ED number conversions between 1920 and 1930 censuses, and 1930 and 1940.

NARA has put ED information for each census on microfilm. Series A3378 has ED maps for 1900 through 1940; series T1224 has descriptions for 1830 through 1890, and 1910 through 1950. T1210 has ED text descriptions for the 1900 census.

Answer provided by Allison Dolan and Diane Haddad

Q: I know we’re years away from accessing 1950 census data, but is there a way to see the 1950 enumeration district maps now?

A: Enumeration districts (EDs) were administrative divisions of a county or township for the purpose of conducting the census. Before today’s online census indexes—and when the 1940 enumeration was first released in April 2012, but not yet indexed—you’d use the ED to identify the roll of census microfilm listing your ancestor’s household. Just as the underlying geography changed over the 10-year span between federal censuses, so too the EDs were redrawn.

Any 1950 ED maps probably won’t be put online until we get closer to the release of that census in 2022 (after the 72-year privacy period expires). Boundary descriptions of the 1950 EDs, but not the maps, are on National Archives microfilm publication T1224, which describes EDs for 1830 through 1890 and 1910 through 1950.

Local public and academic libraries may have 1950 ED maps, so it’s worth checking the catalogs of repositories in areas of interest. The University of Chicago library, for example, has six ED maps from the 1950 census.

You can see what genealogists have to look forward to when the 1950 census becomes public by viewing the forms at U.S. Census website. Like the 1940 census, the 1950 questionnaire included extra questions to be asked of only a sampling of households—it’s not too soon to start hoping your families were included.

Answer provided by David A. Fryxell

A version of this article appeared in the September 2013 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Accuracy and inaccuracy in the census

Jump to a question:

Q: How accurate is the census? How often did enumerators get things wrong?

Q: The 1900 census in Tennessee shows my mother as born in 1895. In 1910, she’s listed as born in 1900. How can I verify which birth date is true? I can’t find a birth record in Tennessee for either year.

Q: Were census takers told to have residents spell their names and children’s names, or did census takers just record their own interpretations?

Q: Can you explain the absence of some family members from federal census reports, when their obituaries indicate that they were residents of the city during that time?

Q: How accurate is the census? How often did enumerators get things wrong?

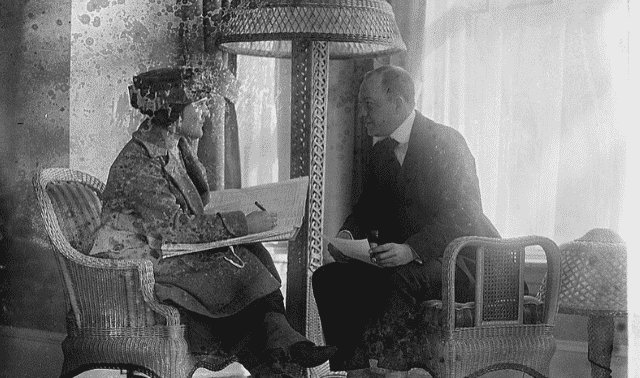

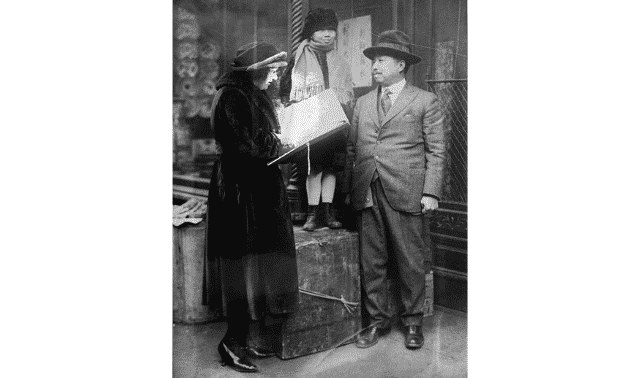

A: Starting in the late 19th century, US census enumerators went through training for their jobs. They were often teachers and postmasters in their daily life—in other words, they were used to writing. They sometimes missed families or made errors as a result of communicating with people who spoke different languages, dialects or accents.

A more common source of mistakes was the people supplying the census data: Sometimes just one family member—even a child—reported for the whole household, and other times neighbors gave information for people who weren’t home when the enumerator came through town. And then there were people who misreported details such as age, out of ignorance or vanity.

So although you could say that the census is only as good as the people reporting the information, the great majority of that information was accurate—which is pretty remarkable, considering the millions of individuals listed—and gives researchers a good foundation upon which to build a pedigree. If you look at the accuracy of genealogical records on a continuum, census records probably aren’t as close to error-free as personal documents (such as birth and marriage certificates), but they aren’t nearly as error-ridden as secondary sources (such as county histories).

For a better historical sense of the enumerations and enumerators, read newspaper reports from the time the census was taken, recommends expert Kathleen W. Hinckley, author of the book Your Guide to the Federal Census (Betterway Books). “I found a huge variety of examples ranging from hilarious to sad to historically important,” she says—everything from a woman jumping out a window because she was fearful of deportation to an enumerator who saved someone who was trying to commit suicide.

Answer provided by James M. Beidler

Q: The 1900 census in Tennessee shows my mother as born in 1895. In 1910, she’s listed as born in 1900. How can I verify which birth date is true? I can’t find a birth record in Tennessee for either year.

A: Our ancestors weren’t as meticulous about dates (or spellings) as we might like, so sometimes such information conflicts. Unless you can find evidence such as a birth certificate or baptismal record (and assuming you’ve examined the original records to verify what they say), your best strategy is to rely on what a court might call a “preponderance of evidence.”

Look for other records that provide a birth year: a marriage record, cemetery record, Social Security Death Index, obituaries, later censuses, state censuses (unfortunately not applicable in Tennessee), military records and so on. If most of these sources agree, even with a few outliers, you can assume the most common date is correct.

Lacking additional clues as to your mother’s birth date, you can guess that the record generated closest to the event is more likely to be correct. In this case, it’s unlikely an infant would’ve been misdated as a 5-year-old; the 1895 date is probably correct.

Answer provided by David A. Fryxell

Q: Were census takers told to have residents spell their names and children’s names, or did census takers just record their own interpretations?

A: Knowing census takers’ marching orders helps illuminate what’s on the records and why. You can download a PDF with all the instructions given to enumerators, as well as sample post–1820 census forms, from the Census Bureau website.

Beginning with the 1790 census, the enumerators submitted returns in whatever form they found convenient, so long as “each household provided the names of the head of the family.” Starting in 1830, census takers received printed forms to use for recording names.

The 1850 census, the first to list all persons living in the household, had only these directions: “The names are to be written, beginning with the father and mother; or if either, or both, be dead, begin with some other ostensible head of the family; to be followed … with the name of the oldest child residing at home, then the next oldest, and so on.”

In 1870, the directions stated: “The family name is to be written in the first column, and the full first or characteristic Christian or ‘given’ name of each member of the family in order thereafter.” The enumerator was also instructed to use the surname for the first family member with each subsequent family member having a “clear horizontal line” being drawn in the place the name would occupy.

The 1880 census rules stated that the obligation to give the information “is required, if … requested by the superintendent, supervisor or enumerator, to render a true account to the best of his or her knowledge, of every person belonging to such family.” The entry of the name and subsequent surnames was the same in 1890 through 1930.

None of these directions indicate that enumerators asked informants to spell the names of those living in that abode. And as you’ve undoubtedly discovered, enumerators didn’t always get the information right. They didn’t have to be well-educated; they often were political appointments. In some cases, enumerators might not have spoken a family’s language or might’ve misunderstood the name as it was given.

Answer provided by Jana Sloan Broglin

A version of this article appeared in the November 2009 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Q: Can you explain the absence of some family members from federal census reports, when their obituaries indicate that they were residents of the city during that time?

A: Although census takers occasionally missed people, it’s possible that the obituaries are wrong. Grieving people may forget or confuse the dates when a deceased person lived in a particular place. Look for other sources, such as court records or city directories, to double-check the information.

But let’s assume the obituaries are correct. Why wouldn’t you be able to find your relatives in the census? They may have been counted, but are playing hard-to-get. And locating them may be just a case of learning to play along. For example, the enumerator could have misspelled the surname so badly that you simply don’t recognize it. Have you checked every conceivable spelling of your name? For example, Mitcham might have been recorded as Machun, Mecham, Meekin, Maikin, Machen or even Meachon.

Expand your search to include phonetic spellings, particularly at the beginning of a name. For instance, Ghoggin might have been spelled Goggin. If your name begins with an H, the H may have been dropped and a vowel used in its place, such as Yaeger or Ager for Hager. Search the Soundex — an index that groups similar-sounding names — to find such variations. Microfilmed Soundex indexes exist for 1880 and later censuses; you can search any online census index by Soundex code.

It’s also possible that the census taker got your relative’s first name wrong, or listed his middle name instead of his surname. My grandfather appears on a census as Byron, although his first name was Herschel. If you find someone with the right surname but the wrong first name, don’t discount him — he may be yours. Confirm it in other records.

If you’re sure the family lived in a certain city at the time of the census, try to track down the listings for neighbors or other family members. You never know — your relatives may have been living in another household.

Lastly, don’t confine your search to where you think your family should be. Expand into nearby areas. County names change and boundaries migrate, so check records for all possible counties.

An excellent resource for locating hard-to-find ancestors in the federal census is The Genealogist’s Companion and Sourcebook, 2nd edition, by Emily Anne Croom (Betterway Books).

Answer provided by Nancy Hendrickson

A version of this article appeared in the October 2004 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Census records of the 1800s

Jump to a question:

Q: I’m seeking the parents and siblings of my great-great grandfather James W. Crutchfield, born July 6,1811, in Orange County, NC. Because the census didn’t list anyone but the head of household until 1850, I’ve been unable to determine who my great-great-grandfather’s parents and siblings were. What resources can I consult to find them?

Q: What happened to the 1890 US census?

Q: What states besides Idaho are reconstructing the 1890 census?

Q: Are any states besides Idaho reconstructing the 1890 census? I’m interested in Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Georgia, North Carolina, Oklahoma and Tennessee.

Q: I’m seeking the parents and siblings of my great-great grandfather James W. Crutchfield, born July 6, 1811, in Orange County, NC. Because the census didn’t list anyone but the head of household until 1850, I’ve been unable to determine who my great-great-grandfather’s parents and siblings were. What resources can I consult to find them?

A: Many researchers have problems hurdling the pre-1850 barrier, when censuses name only the heads of household and provide statistical information about the other household members. But all is not lost — first, check published family histories and online sources, such as databases and online queries, to see if someone has already researched your ancestor. Type his name into a search engine such as Google, and see what comes up. Remember: Information you find in a published family history or online may be inaccurate, so you need to follow up with original sources.

If that route leaves you at a dead end, dive into original records — such as land, tax, probate and court records — for your ancestor and other people with the same surname. Since your ancestor would have been about 29 in the 1840 census, see if he’s listed as a head of household — and note others in that area who have the same surname. For example, list any male Crutchfields in the 1840 census who are the right age to be your ancestor’s father. And note other Crutchfield men who were close in age to your ancestor — they could be your ancestor’s brothers. Then, explore these possible relationships using other records.

In 1830, your ancestor would have been about 19. Check that census: Is there a Crutchfield household in Orange County, NC, with a young man of that age? If so, research the head of that household to determine whether he’s your ancestor’s father.

Finding parents and siblings of a pre-1850 ancestor is challenging: You have to look for potential family connections—people with the same surname in the same place—and explore original records to determine whether they are actually related to your ancestor.

Answer provided by Sharon DeBartolo Carmack

A version of this article appeared in the October 2003 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Q: What happened to the 1890 US census?

A: The 1890 census is a sore subject for genealogists: It sparks bad dreams, anguished “if only”s and anxieties over brick walls. Why? More than 99 percent of records from the census were destroyed Jan. 10, 1921, during a fire in the basement of the Commerce Building in Washington, DC.

When the fire broke out, firefighters flooded the basement with water. The flames didn’t spread to upper floors, but the 1890 census records—piled outside a storage vault—were soaked. (Even some of the census schedules stored inside the supposedly waterproof vault got wet.) The cause of the blaze couldn’t be determined.

The records sat in storage for a while, and no restoration efforts were made. Rumors circulated that they’d be disposed of; various groups protesting such measures were assured the rumors were unfounded. But sometime between 1933 and 1935, the records were destroyed along with other papers the Census Bureau deemed no longer necessary.

Fragments of the 1890 census bearing 6,160 names later turned up; they’re on microfilm and websites such as Ancestry.com. Also surviving are special schedules of Union veterans and their widows for half of Kentucky and states alphabetically following it.

In a precursor to the 1921 tragedy, an 1896 fire damaged 1890 supplemental schedules of mortality, crime, pauperism and “special classes.” They were later destroyed by order of the Interior Department.

Answer provided by Diane Haddad

Q: What states besides Idaho are reconstructing the 1890 census?

A: A fire destroyed most of the 1890 US census, but fragments for several states made it through. The 1890 special schedules of Union Civil War veterans and their widows survived for half of Kentucky and for states alphabetically after that. The National Archives and Records Administration has a list of 1890 census microfilms at .

State archives manage some reconstruction projects, such as Idaho’s, and genealogical societies oversee others. You can find projects on Cyndi’s List and by searching Google for a county or state name and 1890 census. Subscription site Ancestry.com has several 1890 census substitutes, too. Also scour genealogical society websites, online bookstores and library catalogs for substitutes published by researchers.

Don’t forget that you have access to the same records as the people conducting census reconstruction projects. You can look for your ancestors in tax lists, state censuses, voter rolls and city directories.

Answer provided by Diane Haddad

A version of this article appeared in the June 2006 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Q: Are any states besides Idaho reconstructing the 1890 census? I’m interested in Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Georgia, North Carolina, Oklahoma and Tennessee.

A: The Department of Commerce fire that destroyed most 1890 census records is a research brick wall—but it’s one you can get around.

Fragments of the 1890 census bearing 6,160 names from states including Illinois, Ohio, Alabama, Georgia and North Carolina survived and are available on microfilm. The 1890 special schedules of Union Civil War veterans and their widows survived for half of Kentucky and for the states occurring alphabetically after that.

Census reconstruction projects involve using county, state and federal records to approximate who would’ve been around for the missing census. State archives manage some projects, such as Idaho’s, and genealogical societies oversee others, such as Trimble County, Kentucky’s. Find projects on Cyndi’s List and by doing a Google search on a county or state name and 1890 census. The subscription service Ancestry.com has several 1890 census substitutes.

Researchers sometimes publish census substitutes, such as Prairie County, Ark., 1890 Census Reconstruction by Margaret Harrison Hubbard (self published).

Starting in 1866, California regularly collected voters’ information for its “Great Registers.” Registers after 1900 are on Ancestry.com, but the California State Genealogical Alliance published The California 1890 Great Register of Voters indexing 311,028 men living in California in 1890, now available on FamilySearch.

Find similar resources for your ancestral counties by scouring genealogical society websites, online bookstores and library catalogs.

If you can’t find a census reconstruction for your ancestors’ counties, remember: You have access to the very same records as the people conducting such projects. Look for your ancestors in tax lists, state censuses, voter rolls and city directories.

Answer provided by Diane Haddad

Other census questions

Jump to a question:

Q: I found an older husband and wife with the maiden surname of my ancestor living next door in the census—probably her parents. But how can I be sure?

Q: In the 1910 federal census of Racine, Wis., I found the abbreviations M0, M1 and S for marital status. The M means married and the S is for single, but what do the 0 and 1 stand for?

Q: My relative was in foreign countries with the Armed Forces during the censuses of 1950, 1960 and 1970. Where are these records kept?

Q: I found an older husband and wife with the maiden surname of my ancestor living next door in the census—probably her parents. But how can I be sure?

A: With candidates to search for, you can try to find birth records or earlier census records that provide evidence of this couple having a daughter with the right name and age as your ancestor. You also can search forward in time from the clue you’ve found, seeking a will or probate records that mention the daughter by her married name.

Those records may be difficult and time-consuming to track down, so here’s another idea: See if you can find a death certificate for either of the possible parents, especially whoever died last. Who signed the certificate as the “informant”? It could be the daughter or her husband.

For example, Effie E. Miller appears on the 1900 census in Black Creek township, Shelby County, Mo., under her newly married name of Effie E. Forman, with husband Walter. Next door are Henry and Mary Miller—coincidence?

Fortunately, Missouri has an online database of death certificates, with images available for 1910 to 1962. The 1924 death certificate for Henry Miller, born March 20, 1842 (matching his age in the census), not only gives his father’s and mother’s names and states of birth—how helpful!—but was signed by … Effie E. Forman. Though she’s not labeled as his daughter, you can certainly proceed on that safe assumption given the evidence.

Answer provided by David A. Fryxell

A version of this article appeared in the July/August 2013 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Q: In the 1910 federal census of Racine, Wis., I found the abbreviations M0, M1 and S for marital status. The M means married and the S is for single, but what do the 0 and 1 stand for?

A: According to the 1910 US census instructions, the enumerator had to ask if the person was “single, married, widowed or divorced.” (Go to the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series database and click User’s Guide to see enumerators’ instructions for all the federal censuses.) He was to record an S in column eight for unmarried subjects, Wd for widowed, D for divorced and M for married. The enumerator was supposed to inquire about previous spouses and write M1 for a first marriage and M2 (married more than once) for a second or subsequent marriage.

Joseph C. Hamata was the enumerator for the 1910 census in Racine’s Ward 7 (you’ll find the ward and the enumerator’s name at the top of census returns). Hamata wrote M0 in column eight for Leona and Edward Pulda, a couple living in the household of Hannah Dischler – they’re noted as Dischler’s daughter and son-in-law. Column nine, the length of the marriage, is blank, as is the column 10 space for children born to the mother. (Offspring born prior to a woman’s current marriage were included; no code differentiated children born out of wedlock. Stillborn babies weren’t counted.)

If a person married after April 15 – the “official” enumeration date used to calculate ages for the 1910 census – and before the date the census taker visited, he or she would be recorded as single. A similar policy applied for widowed people. The enumerator was to use a 0 in column nine for couples wed less than a year as of April 15.

Since the M0 notation is unusual, I looked for similar entries in the rest of Hamata’s census territory and found none – he seems to have followed his enumeration instructions quite well. My guess? Edward and Leona weren’t actually wed, but Leona used his surname, suggesting a common-law marriage. I recommend looking for them in Racine County marriage records to check this theory. Your other genealogical research also might reveal an explanation behind the Puldas’ living arrangement.

Answer provided by Jana Sloan Broglin

A version of this article appeared in the September 2007 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Q: My relative was in foreign countries with the Armed Forces during the censuses of 1950, 1960 and 1970. Where are these records kept?

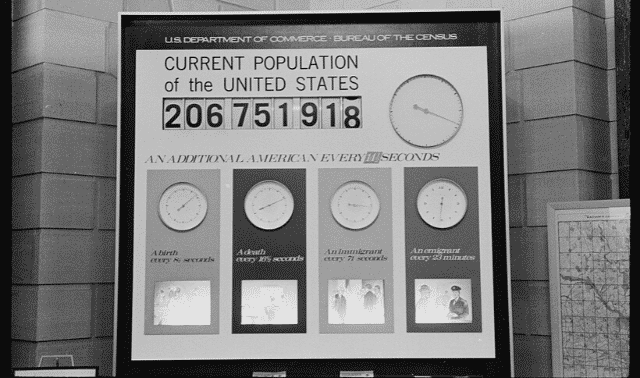

A: Federal censuses, taken every 10 years since 1790, are some of the most useful genealogical sources. Records can provide ages, birthplaces, marital status and immigration and military service information. Laws restrict access to censuses for 72 years; enumerations from 1930 and before are available online at Ancestry.com (by subscription) and HeritageQuest Online (free through subscribing libraries), and on microfilm at many libraries.

When the 1950, 1960 and 1970 censuses become available to the public, they’ll provide information about military personnel serving overseas. Military units, including those stationed at battlefronts, were required to fill out census forms and return them through the chain of command to the US Census Bureau. Censuses counted active servicemen and women (except officers) with their military unit, not their civilian household, beginning in 1920. Officers were listed with their families.

In lieu of the census, find a family member who served overseas during the mid-to-late 1900s by running a Google search for information on military units. Many regiments have websites, such as the 327th Infantry Veterans Screaming Eagles and the 30th Field Artillery Regiment Association Hard Chargers, devoted to veterans who served with them. These sites may have rosters, historical data, contact information and calendars listing reunions and other events.

Remember, the primary purpose of censuses is to determine states’ representation in Congress. People living overseas, both civilian and military, aren’t counted in those totals. Interestingly, except for Vietnam, the US military hasn’t been involved in a major war during any census. For more information, see Americans Overseas in US Censuses.

Answer provided by James W. Petty

A version of this article appeared in the February 2007 issue of Family Tree Magazine.