Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Sometimes the best we can do for a “date night” at our house is hanging out in the living room while my husband watches a game and I do genealogy on the laptop.

On one of these thrilling evenings, I was using the Cincinnati Birth and Death Records (1865-1912) database, a card index created long ago from city vital registers. I kept remarking on the death records of infants I’d come across. Each one made me more grateful for my two healthy (I’m crossing my fingers and knocking on wood right now) little ones.

Greg was feeling the same way. He wondered how a genealogist today could even know to look for a baby who died at a few hours, days or weeks old before official birth and death records began.

You could form a hunch based on long gaps between children, or maybe oral tradition, a tiny headstone, a letter or another home source would be a clue. There’s also the census: The 1900 and 1910 censuses had columns for women indicating “mother of how many children” and “number of those children living.”

I realized then that I’d always assumed my great-great-grandmother Frances (Ladenkotter) Seeger hadn’t lost any of her children. I hadn’t found any records indicating that was the case, and no infant’s headstone is in the family plot.

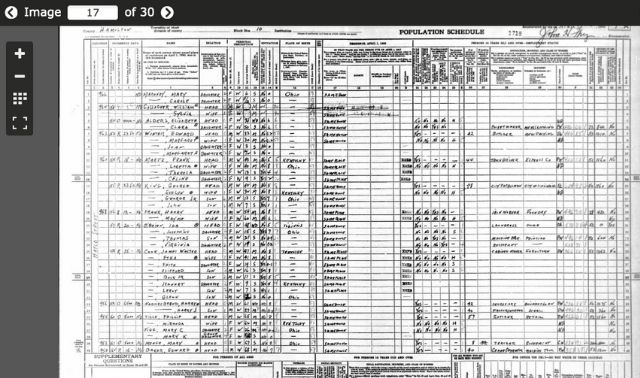

Sure enough, when I looked again at her listings in the censuses for 1900

and 1910

those two columns showed a nine and a seven. Two of her babies had died. (Of the 12 mothers on the 1900 page, only two had the same number in both columns.)

I looked for them in the Cincinnati database of births and deaths. Joseph Heinrich died in 1877 at 29 days old of “pyaemia result of dorsal abscess” (septicemia related to an abscess on his back). I also found his cemetery burial record (which had his name).

I found the birth of the second baby, Mary, on Aug. 2, 1878.

I may have found the death: This card, for a baby who died of premature birth at two hours old, has the right address, date (“8-3-78,” which would mean a birth shortly before midnight), and a close last name (Suger), but the baby’s name is Herman instead of Mary.

Either the birth or death card could have an error carried over from the original registers (which still exist, apparently, but are fragile and not available for research), or one made in transcription. I haven’t had any luck searching cemetery records, either.

Details about a relative who died as a newborn more than a century ago might or might not provide leads to additional genealogical information. Either way, putting these babies on the family tree matters to me, as I’m guessing it does to other genealogists. It creates a truer picture of your ancestral family, and more important, it keeps a brief little life from remaining unknown.