A will is a legal declaration a person (the testator) makes that nominates one or more people—executor, executrix, personal representative or administrator—to manage the disposition or distribution of his or her property at the time of death. A probate court oversees the legal process.

A lawyer or other official can prepare the document, or the testator may write it by hand (called a holographic will). The testator must sign the will for it to be legally valid, typically in the presence of witnesses who will later attest that they saw the person sign. This is an essential part of the probate process. Wills not witnessed are validated in some other way, such as sworn statements by those close to the testator.

A will typically contains instructions regarding disposition of the testator’s physical remains; payment of expenses and debts; collection of debts owed; and distribution of assets. Other provisions might include placing an inheritance in trust for a surviving spouse to provide an income over time, with a person, bank, corporation or public body assigned trustee.

A testator can change his or her will by signing a new document. The latest version of the will is called the last will and testament. A person also can revise an existing will with a codicil, often used to make an immediate change until a new will can be produced. The testator may or may not sign a codicil.

A person who didn’t leave a will is said to have died intestate. Depending on the law and the size of the estate, a probate court may hear potential heirs’ testimony and make judgment on the estate.

The court’s file of documents presented throughout the probate process may include an inventory of the estate; names of potential beneficiaries; and correspondence related to debts and debtors, business partners, relatives, slaves, etc. Don’t overlook court minute books noting estate-related matters.

County will books from the early 20th century and older usually hold transcriptions of original wills. These may contain errors or omissions, so it’s important to locate the original will in the probate packet. Later probate records typically include the original will. Some wills may have been microfilmed and/or digitized; check the court website and FamilySearch.org.

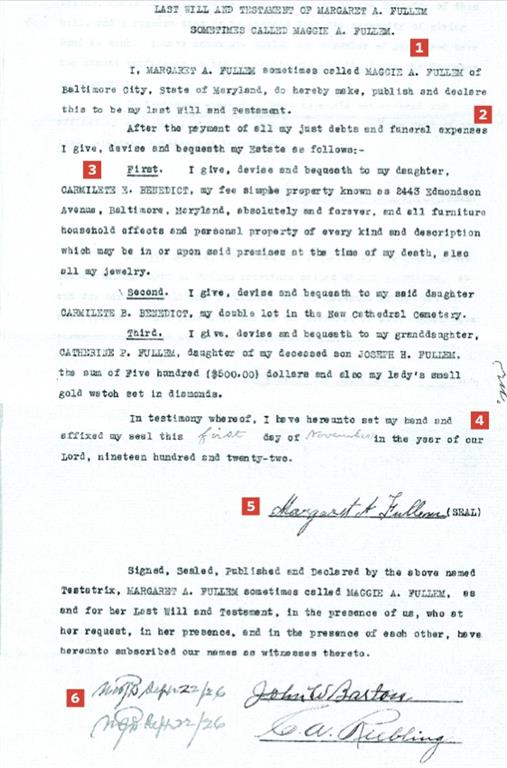

Let’s look at a sample will and the clues you can find in it.

1. The testator states his name, and sometimes a nickname he also goes by. A testator may assert he’s mentally competent to make this will. Other verbiage may refer to religious beliefs.

2. The testator indicates that debts and expenses be paid as promptly as possible. Funeral and interment instructions also may be included.

3. The body of the will enumerates specific beneficiaries and bequests. The testator may give instructions for distribution in the event that a named beneficiary dies before the will is probated. Instructions to establish a trust or other arrangements would be included here.

4. The date the will is executed appears before the testator’s signature.

5. If the testator is unable to sign the will, he or she may make a mark.

6. The witnesses who were present when the testator signed the will sign their names. The date of their signatures is assumed to be the same date the testator signed. Some wills include the address of each witness. A notarized will may include the notary’s signature and date his commission expires. Original wills in the possession of the court may include the date on which the witnesses’ sworn statements were taken to prove the testator’s signature.

A version of this article appeared in the January/February 2015 issue of Family Tree Magazine.