Where should I look for an ancestor’s will?

Q: I know wills can be a great resource for genealogy, but I’ve never looked for one. Where should I look for an ancestor’s will?

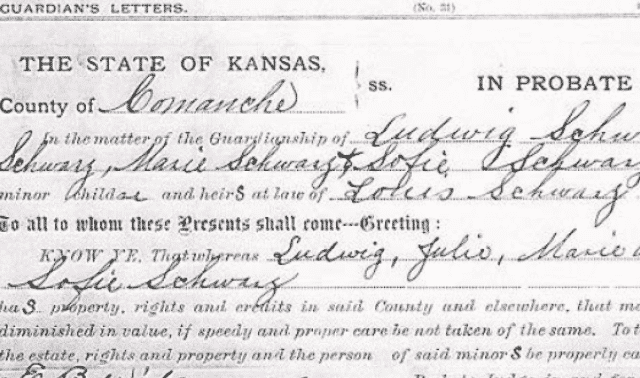

A: Probate packets (which contain wills if the deceased left one) and wills recorded in will books are held at the county courthouse where the will was filed, unless the records have been transferred to a state archive. They’re rarely online.

Not all states call their probate courts the same thing, which can be confusing. The jurisdiction that recorded the will might be called a superior court, circuit court, district court, chancery court, register of wills or surrogate’s court. Check The Family Tree Sourcebook (Family Tree Books) or Ancestry.com’s wiki for county courthouse addresses and the name of the appropriate jurisdiction.

Probate records are usually indexed. They’ll be listed by the name of the testator (the person who left the will) or intestate person (a person who died without a will), not by the heirs named in the will. Here are some tips for finding your ancestors’ wills:

- Working from the date your ancestor died, check microfilmed indexes of wills through the Family History Library in Salt Lake City. You can access the library’s catalog online. Run a place search for the county and state your ancestor last resided or died in, then look under “probate records.” You’ll get a list of the resources available on microfilm. You can order the microfilm through one of the 4,000 worldwide Family History Centers.

- Once you have the volume and page number from the index, order the relevant film(s). If the FHL doesn’t have microfilm of the records, write to the courthouse to request the records. Sometimes the FHL has an index to probate records, but not the actual records. In that case, use the information from the index to request the will from the probate clerk.

- If the FHL doesn’t have a microfilmed index for the time period your ancestor died, you can still write directly to the probate clerk and ask if your ancestor left a will. Give your ancestor’s full name, date of death and any other identifying information. Include a self-addressed, stamped envelope so the clerk can tell you if the record is there and what the fee is to obtain a copy. Remember to ask if the entire probate packet exists and how much it would cost to copy it.

Another useful resource is an abstract of wills. Genealogists sometimes make these available to us by publishing a summary of the important aspects of the wills in a will book, leaving out the legal mumbo-jumbo. You might find published abstracts for your ancestor’s area through the FHL (although printed books don’t circulate to FamilySearch Centers) or at a genealogical library in your ancestor’s town. Try searching the WorldCat online catalog of holdings at libraries around the world.

Some abstracts and indexes are popping up online; try a search engine such as Google and check the county USGenWeb site. Always then seek the original will or the recorded copy of the original in the courthouse.

Answer provided by Sharon DeBartolo Carmack

My family’s records were lost to a courthouse fire. Now what?

Q: I’ve traced my family to a county whose records were burned in the Civil War. Is this a brick wall I won’t be able to break through?

A: One of the many losses of the Civil War was the destruction of countless courthouse records in fires. But don’t give up if your ancestors made their homes in one of these burned counties — there’s still hope.

The courthouse might not have completely burned down, or, if you’re really lucky, the county might’ve had two courthouses. If you contact the county courthouse and are told the records were destroyed, don’t stop there. Pounding the pavement could pay off.

“In my experience, I’ve heard a particular courthouse’s records were burned, but when I visited in person, they were all there. It was just a rumor — or an assumption by someone who didn’t know better,” says Family Tree Magazine contributing editor Sharon DeBartolo Carmack. “My advice is to check guides specific to the county or state written by knowledgeable genealogists to learn what records went up in smoke.”

Carmack recommends Virginia Genealogy: Sources & Resources by Carol McGinnis (Genealogical Publishing Co.), which reassures frantic genealogists that many missing or stolen county records resurface in other places. During times of war, records were often relocated for safekeeping in another county or state. For example, some Virginia records carried off during the Civil War later turned up in Pennsylvania. But, McGinnis writes, many county records sent to Richmond for safekeeping during the war ended up being destroyed in that city’s devastating 1865 fire.

In some cases, burned counties rebuilt their records by asking residents to bring in copies of deeds, wills and vital records. Be sure to check neighboring counties’ repositories, as well as those of any parent or child counties.

Sometimes counties put their charred records under the auspices of local historical societies. Contact them to find out more about their holdings. Then do a place search of the Family History Library’s online catalog on the county and state.

Answer provided by Lana Taylor Figgs

A version of this article appeared in the July 2008 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Do heirs have to be related in a division of property?

Q: Why would a couple be listed as heirs in division of property of a deceased person unless they were related in some way?

A: Key words here are couple, heirs and related. Was heir used in the document? Were other people named in the division besides the couple in question? Have you identified the others as relatives of the deceased? If not, research and identify each one. Other documents related to the case may help.

Without more information, we must generalize. Frequently, heirs were the spouse, children, parents or siblings of the deceased, depending on the circumstances.

If a child or sibling of the deceased had died, his or her children could have received and split that share of the estate. If a husband and wife were listed among heirs, usually the wife was the heir and her husband was receiving the inheritance “in right of” his wife since married women, for so long, were not legally able to inherit or own property in their own name. Thus, heirs named in a division were usually related by blood or by law (such as adoptees), but interpretation depends on the wording and other specifics of the case.

For example, was the division based on a will? What did the will provide? Did it name heirs and their relationship to the deceased? Did it name devisees or legatees? These were not always relatives because the testator (the one writing the will) could leave property to anyone of choice, related or not. Was this an intestate estate (one without a will)? What was the law of heirship at that time in the state where the deceased died? State law dictates who are legal heirs of an intestate estate if the deceased had no surviving spouse, children, parents or siblings. Heirs may then be descendants of parents’ or grandparents’ siblings—cousins of varying degrees.

Answer provided by Emily Anne Croom

Are heirs listed on estate records children of the deceased?

Q: I have the estate record of Isaac Cornelius, who died in Muskingum County, Ohio, in 1822. Not one family member was paid money from his estate, except a Jacob Cornelius who is not found anywhere in Ohio records. According to land records from Muskingum County, this Isaac’s heirs were Elizabeth Cornelius, Sarah Cornelius, Christopher Cornelius (our direct line), William Cornelius, etc. Would the names of these people have been Isaac’s children? It clearly states in the land records from Ohio that these people were Isaac’s heirs.

Also, in 1807 Huntingdon County, Pa., records, an Isaac Cornelius was imprisoned for bad debts. He turns over his personal property to a Jacob Cornelius for handling of his debts. When Isaac was released from prison he disappears from Pennsylvania records. I believe the Isaac who was imprisoned is the same Isaac who purchased land in Muskingum County, Ohio, in 1814 and was counted in the 1820 census. He must have died in 1822 since a Jacob received money from his estate.

A: The names of Elizabeth, Sarah, Christopher, William, and others as his “heirs” would indicate they were related to him and to each other, especially since the surname is the same. Did Isaac have a will, or did he die intestate (without a will)? Did his wife survive him? Are there additional probate or guardianship records in the county records?

If Isaac left a will, it may clear up some of these questions. Have you looked for minute books of the court of common pleas in Muskingum County to look for any further information about Isaac’s probate? If the heirs were minors, even tax records (if they exist) could indicate their relationship to Isaac.

If Isaac died intestate as a widower and the heirs were selling equal shares in his property, then they normally would have been his children. If they were selling the entire piece of property, not just portions or their shares of it, it would appear they were all his surviving children. If such a person as Isaac had no children, heirs normally would be brothers and sisters with equal shares, or their children splitting a deceased parent’s share.

Do the names in the land records appear to match Isaac’s family’s makeup in the 1820 census? Do the land records indicate that the sellers had different shares of interest in the estate? Have you identified or studied further all the listed heirs? Sometimes, deed records do not spell out shares of interest but just list the names. Then it is up to the researcher to determine whether one may have been his widow or some may have been grandchildren whose parent-and-heir was deceased. Much also depends on the individual circumstances of the case, such as Isaac’s age and marital status when he died.

As for the Pennsylvania Jacob and the possible Pennsylvania connection of Isaac, you may be on to something. Have you studied Isaac’s children in censuses of 1880 or after, if they lived that long, or in death records? Do they indicate Pennsylvania as a birthplace of their father? Were any of Isaac’s children born in Pennsylvania, as suggested in their census, death, or other records? You also need to study that Jacob in Pennsylvania records. Was he of age to be a son or nephew of Isaac? Or perhaps a brother or cousin or father?

Identifying the one Jacob’s relationship to Isaac, as suggested in Isaac’s estate record, would depend on the wording of the record. Was he paid money as “his share” of the estate (which would usually indicate a son or a specific bequest from a will) or in the capacity of administrator, executor, guardian of minors, or someone to whom money was owed? Keep an open mind that the two Jacobs could be two different men or could be the same person. You can also check on Ohio probate law at the time of Isaac’s death to see if there may be other possibilities to help explain the estate information you have.

Answer provided by Emily Anne Croom

How do I track my ancestor with a criminal record?

Q: I discovered my great-great-grandfather in a listing of “black outrages against whites” in North Carolina. The microfilmed court docket says my ancestor was found guilty in 1867 of assault with intent to kill, but no sentence was recorded. I can’t find him in the 1870 or later censuses. What should I do next?

A: Your ancestor’s family was undoubtedly changed by his conviction. Here are three strategies for tracking criminal ancestors:

1. Use what you already know: Getting the microfilmed court docket was a good start for learning your ancestor’s fate. Now you need to learn what happened after the trial. Try court-minute and court-order books. The sentence may be recorded there, or in separate judgment books. Look to newspapers of that area and time period for details. Check local and county histories for clues to where prisoners may have been incarcerated, and then recheck the 1870 census for those institutions. The county courthouse and state archives will most likely house county jail and state prison records, as well as parole board and pardon records.

2. Dig deeper: Your ancestor may be an exception to typical ancestral patterns. Although some accused criminals skipped town or changed their identities to escape their pasts, many stayed put. Persist in your search through all the familiar genealogical sources, but also check less-familiar ones. Scour indexes to county and federal civil and criminal court records, state and local institutional records, published histories and periodicals. Take advantage of the increasingly powerful search capabilities of electronic indexes and search engines, and go back to them regularly to look for new or updated information.

3. Research the whole family: Apply the search strategies above on a larger scale. You may not be able to find your ancestor in 1870, but what about the rest of his family? Track all descendants, cousins and in-laws forward in time for connections or clues to your great-great-grandfather’s whereabouts. Do the same for other people with whom he had close associations. Was he married with kids at the time of the trial? Look for a guardian appointed over his children. Check civil court cases for a separation or divorce. Use census, land and probate records, which might indicate family members’ migrations. Investigate local and religious newspaper obituaries for all the relatives. If you’re lucky, one of these might list him as a surviving relative.

Above all, be persistent. The ancestors who got in trouble usually created records, and are often the most interesting part of the family.

Answer provided by James W. Warren

A version of this article appeared in the February 2006 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Courthouse Records Problems and Solutions

Problem: In some counties, courthouse personnel won’t search indexes for genealogists (although they will make a photocopy if you give them an exact citation for a record).

Solution: Hire a researcher to look for your records.

Problem: Most states have closed recent vital records to protect living people’s privacy. To request these documents, you must be either the person named in the record or a close relative or legal agent.

Solution: If you have the person’s consent to get the record, write a letter in that person’s name and have the person sign it.

Problem: Some courthouse employees respond to genealogists immediately; others take several weeks.

Solution: Don’t send requests around election time! Before and after primary and general elections, clerks are busy, and requests pile up.

Problem: A repository that should have a record doesn’t find it.

Solution: There are two possibilities: 1. the record doesn’t exist; 2. the person searching didn’t find it. Did you provide the correct information? Did you request the death certificate of a married woman using her maiden name? If you gave the correct information, unless there’s some urgent reason for obtaining the certificate, wait a few months, then resubmit the request. A different person might be able to find it. But remember there’s no guarantee that a record exists—even for dates when registration was required. Some events were never recorded, and some record books were destroyed in fires, floods and other disasters.

Christine Crawford-Oppenheimer

A version of this article appeared in the June 2003 issue of Family Tree Magazine.