Forget “SVU,” “CSI” and “NCIS”: When so much real-life drama lies in the branches of your family tree, who needs prime-time procedurals? Genealogists can find just as much intrigue and scandal at the county courthouse. If you haven’t yet been turned on to court case records, just wait — you won’t be able to change the channel. Start loading up your research docket with our advice for finding and using your ancestors’ court case records.

Types of Court Case Records

Once you start digging in county courthouses, you’ll find records of divorces, name changes, marriages, lawsuits, naturalizations, licenses, foreclosures, debts, land transactions and a host of other procedures. While some groups of records — such as deeds, marriages and naturalizations — typically have their own indexes, the really juicy documents with the v. in the middle (Peabody v. Mitcheltree, for instance) might take some extra digging to find. But don’t rule them out; there’s usually some order in the court records. They fall into three categories:

Criminal

These cases, of course, are the stuff of “Law & Order” episodes. Criminal cases are considered public, meaning the state or local jurisdiction (“the people”) files charges against an individual. If substantiated, the case goes to trial, and the court pronounces a judgment. It sounds simple, but this process creates an avalanche of documents. Types of records you might find include the complaint, the bond or bail, a coroner’s report and inquest, arraignment, testimony documents from witnesses and other evidence, a jury list, trial proceedings, the judgment, and appeals.

Civil

Welcome to the genealogical version of “Judge Judy.” In civil cases, one party (the plaintiff) sues another party (the defendant) in a situation where the plaintiff feels wronged, such as a divorce. Civil court records can contain other material, such as court orders, naturalizations, road work appointments, licenses, name changes, foreclosures, fornication and adultery cases, and cattle-brand or earmark registrations. Some courthouses may have separate volumes for certain actions; early courts might group them all together.

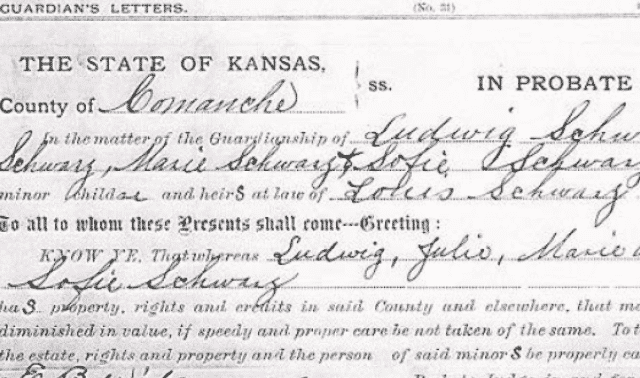

Equity

Also known as chancery records, they involve the resolution of property disputes, such as those stemming from probates, estate divisions and divorces. Judges decide equity cases without a jury. You might find them with civil case records or in separate books. Here’s an example of a chancery court case: The King George County, Va., court appointed William G. Stuart guardian ad litem for his sister Lucy F. Stuart in 1831, when James Madison Fitzhugh and his wife, the former Mary F. Stuart, brought suit in chancery court for the division of their father’s land. Until this time, David Stuart’s minor children had no guardian after his death in 1822.

For more information on types of court records, see Christine Rose’s Courthouse Research for Family Historians (CR Publications).

Legal proceedings

To find criminal, civil and equity disputes and orders involving your ancestors, you’ll need to hunt down compiled abstracts, indexes, dockets, court minutes and order books. These resources will give you the case file number or, in older court records, volume and page numbers, the court term and party names. Most court case files, if they still exist, haven’t been microfilmed or digitized, so you’ll need to write or visit the courthouse to obtain them. More on how to do this later — first, let’s explore five tools you can use to learn if your ancestors had their day in court.

Court record compilations

Look for abstracts or transcriptions of original court records compiled by genealogists and historians. If made properly, these compilations will give you the original volume and page number of the entry, and the location of those volumes. Typical entries look like these from Accomack County, Virginia, Court Order Abstracts, 1719-1724, Volume 14 by JoAnn Riley McKey (Heritage Books):

Ordered that Giles Jones, Silas Chapman, John Dubberly and Cuttburth Russell (or any three of them) inventory and appraise the estate of James Coner before the next court.

Griffeth Savage came before Mr. Richd. Drumond (a justice) and complained that he was in fear that John Sanders would kill or wound Savage’s creatures. Sanders was bound for keeping the peace and appearing at this court. Now when no one appeared to allege anything against Sanders, he paid fees and was discharged.

The best place to find published abstracts is at the Family History Library (FHL) in Salt Lake City. Most volumes haven’t been microfilmed, so you’ll need to visit the library or hire a researcher to check for you. To find abstracts in the FHL catalog online, do a place search for the name of the county. In the results, look for subject headings such as court records, guardianship, orphans and orphanages, poor houses and poor laws. You can view microfilmed abstracts at your local Family History Center.

You also can search for court record abstracts on Ancestry and free sites such as RootsWeb and USGenWeb. Try entering the county name, state and the keywords court records or court abstracts into Google or another search engine.

Indexes

If they exist at all, some indexes might include only the plaintiff’s name, others only the surnames (Allen v. Joynes). Discouraging as that may sound, don’t skip this step — your ancestor’s county might’ve maintained good indexes. (And it’s not all bad news: Recent court records usually have better indexes than those from earlier times.) Look for indexes as you would compilations — online and through the FHL — and see Christine Rose’s Courthouse Indexes Illustrated (CR Publications) for examples of different kinds of indexes. Pay attention to co-plaintiffs and co-defendants — they could be relatives or associates of your ancestor.

Dockets

These books list cases waiting to be heard by the court. If the county is small, you might find just one docket for all cases or, more likely, several dockets for the various kinds of cases: criminal, civil, equity, claims and miscellaneous, in which you’ll find adoptions, commitments, divorces, estates and so on.

Dockets don’t offer a lot of information: They’re more like indexes, giving dates of actions as well as volumes and page numbers. But dockets aren’t always organized how you’d expect — that is, alphabetical by plaintiff, defendant or both. Many are arranged by term of court, which generally met every three months, so it’s best to search with a good idea of when your ancestors appeared in court. (This is why you should search for abstracts first — those are indexed by all the names involved in the case, saving you a lot of research time.)

If you find an ancestor in a docket book, you’ll see all actions related to the case grouped together with dates and case file numbers. After collecting that information, you can look for more dirt in the court minutes.

Court minutes

I’m afraid I’ve seen more unindexed court minutes than indexed ones. (Another reason to look for published abstracts.) You might get lucky and find an index for your courthouse, but if not, you have to search page by page. If you’ve found your ancestor in the dockets, you can focus your search on minutes for specific court terms and dates.

The minute books record all actions taken by the court. Sometimes the notations are lengthy; other times they’re excruciatingly brief. Continuing with our example on the opposite page, the March 1823 court in King George County, Va., summoned Charlotte Stuart, the widow of David Stuart, to appear “to show cause if anything she has or can say why the estate of the said David Stuart should not be put into the hands of the Sheriff for administration.” That’s it. Her appearance and response aren’t recorded. It’s disappointing, but at least I know David’s widow was alive at a given place and time. Sometimes that can be just as important to your research as knowing the outcome of a case. I can surmise Charlotte appeared and gave sufficient evidence, because at the June 1823 court, she appeared and was granted a $12,000 bond, with John G. Stuart and George Fitzhugh as her securities. The court appointed William F. Grymes, Benjamin Grymes and George N. Grymes to inventory and appraise the estate of David Stuart.

Court minutes can make mighty interesting reading. In one entry, you might discover the sheriff ordered the sale of your ancestor’s property for back taxes. The next case might describe a “Savage C. Riggs who is the devisee under the Will of said Daniel Taylor and was an illegitimate son of sd Daniel” (sd meaning “said”). Essentially, any item that came before the court could be recorded here: overseers of the poor, jurors in a case, issuance of business licenses, appointment of guardians, estate reports, apprenticeships and more.

The FHL has many microfilmed court minute books. As with abstracts and indexes, check the FHL catalog under the county, then subject headings such as court records, guardianship, orphans and orphanages, poor houses and poor laws.

Order books

These books record the orders directed to the sheriff or constable. Orders, recorded chronologically, might be part of the minutes or listed in separate books. You could find entries throughout many books for a single case that carried over a number of years. Look for order books in abstracts or on microfilm. Some will have indexes; others won’t.

Once you know your way around the courthouse, getting hooked on the intrigue you can extract from dockets, minutes and case files is inevitable. Before long, those “Law and Order” reruns will seem positively quaint.

A version of this article appeared in the September 2008 issue of Family Tree Magazine.