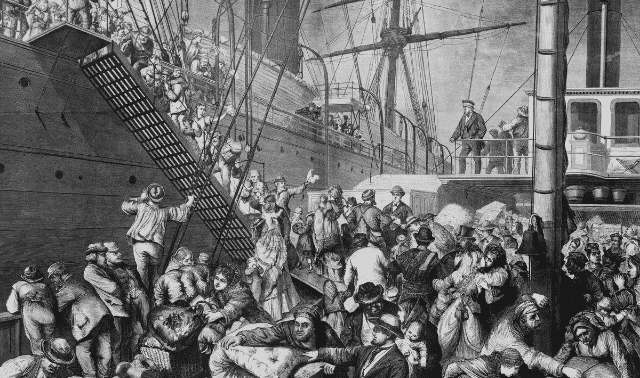

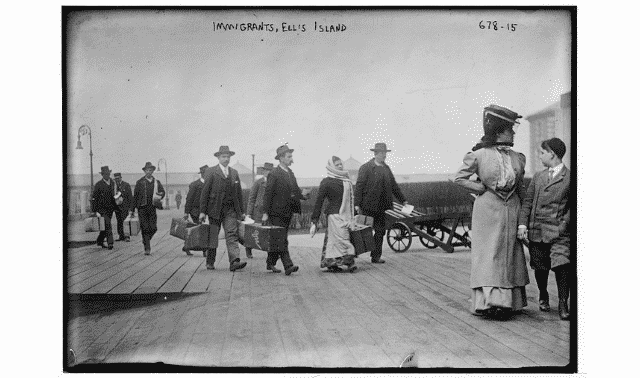

Few “aha” moments thrill genealogists more than finding an immigrant ancestor’s passenger arrival list. Seeing Great-great-grandpa’s name on that manifest, you can almost envision him stepping onto American shores, ready for a new life in the New World. The end of Great-great-grandpa’s journey doesn’t necessarily mean the end of your immigration research thrills, however. Equally exciting discoveries may await you at his port of embarkation.

Departure records are easy to overlook — after all, US passenger arrival lists already supply a wealth of genealogical clues, and departure ports didn’t always create correspondingly detailed counterparts (governments typically were more concerned with keeping tabs on who they were letting in than who was going out).

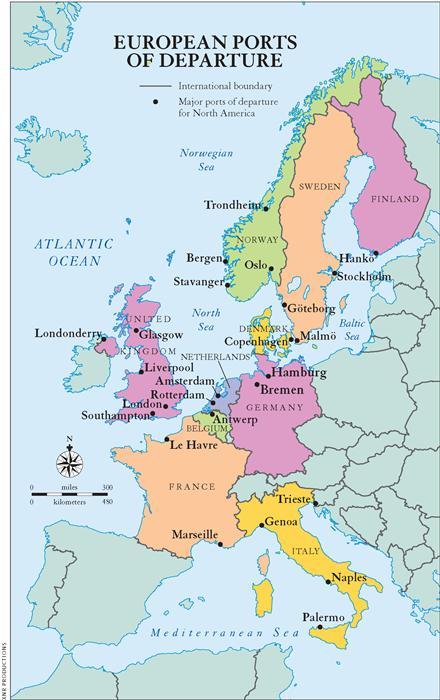

But for many of our immigrant ancestors — roughly a third of all American transplants — genealogically revealing passenger records lie on the other side of the pond. And for more-elusive emigrants, you often can find substantive embarkation record substitutes, such as passport applications, residential registrations and even reconstructed departure lists. So join us as we cruise through the possibilities for documenting your ancestors’ departures. We’ll focus on European ports, since that continent supplied the largest numbers of newcomers, including America’s “great wave” of immigration during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Welcome these resources into your research repertoire, and you’ll say hello to new details about your family’s farewell to the old country.

Find Which Port Your Ancestors Ventured From

First, of course, you have to figure out which port your ancestors ventured from. You may learn this from the passenger arrival list, which typically tells where your forebears’ ship set sail but don’t automatically assume that’s where your family’s journey began. US-bound passengers sometimes changed ships en route; for example, a German emigrating from Hamburg might’ve stopped over in Liverpool, England, on his way to Philadelphia. You also can look for naturalization papers and family letters describing the immigrant’s journey, though these may be a long shot.

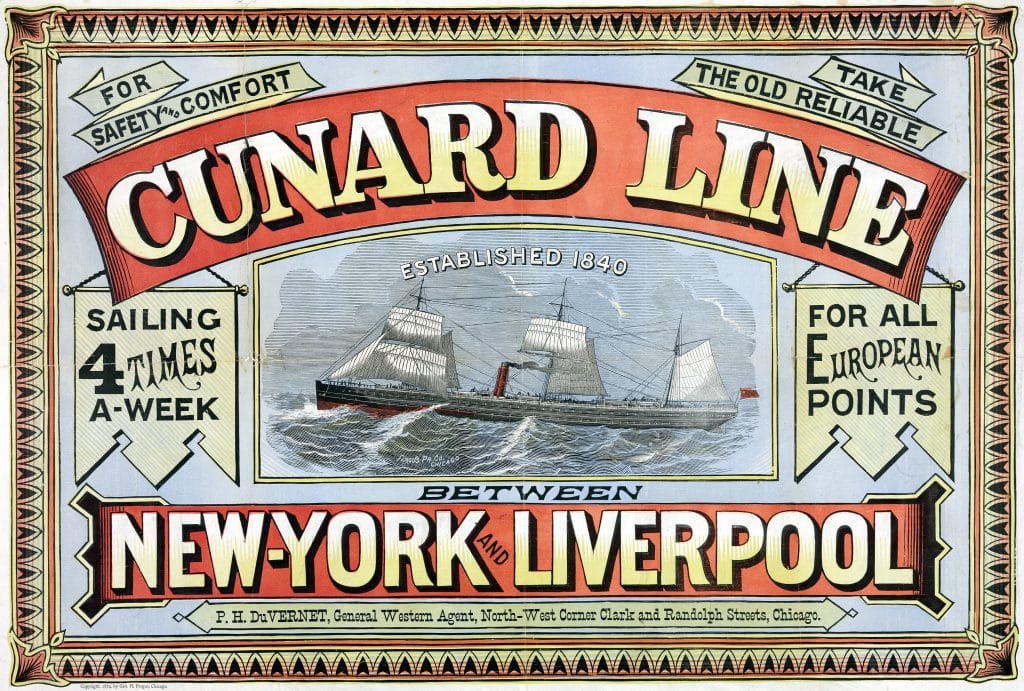

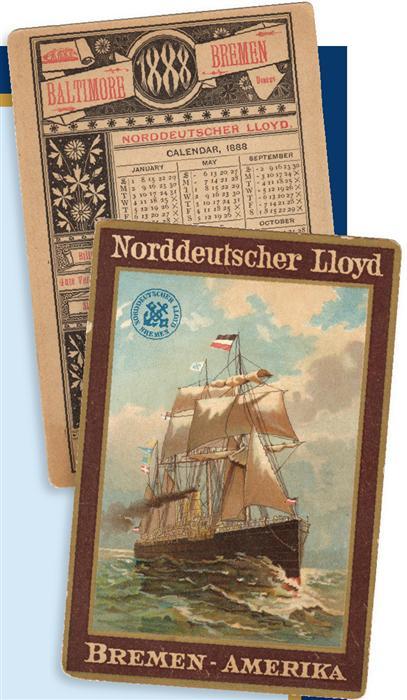

Knowing emigration history can help focus your search. Europe’s embarkation “hot spots” changed over time as different ethnic groups took their turns flocking to America. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the British Isles and southwestern German states supplied nearly all the Colonies’ European settlers. (African slaves made up the largest segment of overall immigrants during the 1700s, but unfortunately, their descendants have relatively few arrival records and even fewer departure documents to work with.) Colonial-era British Isles emigrants typically departed from London, Glasgow, Dover, Portsmouth or Cowes, while the Dutch cities of Amsterdam and Rotterdam were the primary ports for people leaving the continent. By the mid 1800s and early 1900s, America’s immigrants were arriving primarily from northern Germany, Italy and especially Eastern and Southern Europe — including Jews, Hungarians, Czechs, Slovaks and the entire patchwork of ethnicities encompassed by the Austro-Hungarian and Russian empires. During that period, the German ports of Bremen and Hamburg ranked far and away as the No. 1 and No. 2 points of embarkation for the New World. They were the closest ports for people in landlocked Eastern European regions, and shipping companies aggressively advertised their Bremen-and Hamburg-to-America routes there.

Getting Around Missing Bremen Passenger Lists

In fact, more than 7 million European emigrants departed from Bremen or to be more precise, the “harbor of Bremen,” also known as Bremerhaven. Bremen, which sits downriver, established this North Sea port in 1827. Today, the two cities make up the federal state of Bremen, and genealogists generally lump them together when discussing emigration.

Bremen’s government diligently kept departure lists beginning in 1832 and into the 1900s. But if you’ve discovered your kin sailed from there, hold your applause: In a move that still gives a bad name to archivists and the phrase “retention schedule,” the record-keepers authorized the destruction of Bremen’s passenger lists in 1875 to make file space available. (Yes, we see you cringing!) Each year until about 1909, lists continued to be destroyed. Only the three most recent years’ records were spared.

Unfortunately, the news gets worse before it gets better. Although archivists resumed regular records maintenance in 1909, most of the remaining manifests met their demise in WWII bombing raids. Only the 1920 to 1939 lists survived intact.

Members of the Bremen Society for Genealogical Investigation, known as Die Maus (German for “the mouse”), are currently indexing those lists on the society’s website. Thus far, they’ve completed the years 1920 to 1934, covering more than a half million immigrants. You can search these indexes by family or ship name, departure date, destination harbor and the immigrant’s hometown. The website also provides photos of many ships. (Click the To the Database button, then Ship Names. Next, select a voyage and then click on the button with the ship’s name in it.)

But what if your ancestors were among the millions who left from Bremen during the earlier years? Are you stuck? Not necessarily — you can try a few workarounds.

Probably the most important is Gary J. Zimmerman and Marion Wolfert’s four-volume German Immigrants: Lists of Passengers Bound from Bremen to New York. Zimmerman and Wolfert indexed the copies of Bremen-to-New York ship lists that were prepared for Bremen officials but turned in at the destination port instead. The series covers about a fifth of the lists from 1847 to 1871. Also check in major genealogical libraries for monographs published by Clifford N. Smith — they contain 1840s and 1850s Bremen passenger listings gleaned from items published in the emigration newspaper Allgemeine Ausuwanderungszeitung.

German archives hold helpful substitute sources, too. Look for passenger lists from ships involved in court cases at the Bremen State Archives. This repository also has the records of Bremen’s Seemannsamt (board of shipping), which include crew lists and registers of births and deaths aboard the emigrant ships; the documents cover most years the port operated.

For the years 1854 to 1906, Bremen’s state archive holds the records that granted residents permission to emigrate, including the actual applications for release of citizenship. These “Entlassungen von Bewoknern des Landgebiets aus dem bremischen Staatsverband wegen Auswanderung,” as they’re called in German, include many people who lived and worked in Bremen for a time before leaving for America.

Searching Hamburg Records

Ready for some good news? During the 19th century, 5 million European emigrants passed through Hamburg, and (fortunately) the story of this port’s records has a much happier ending than that of its neighbor to the west.

Nearly all the passenger departure lists — divided into “direct lists” of emigrants sailing nonstop and “indirect lists” of those who stopped at an intermediary port before cruising to their final destinations — survive from 1850 on. The Hamburg State Archives holds the originals, which date from 1850 to 1934. You can search this database at Ancestry.com (subscription).

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Family Search Library (FSL) has microfilmed copies of the Hamburg lists, along with several indexes and an excellent guide to using both. From the FamilySearch home page, navigate to the Research Wiki to access The Hamburg Passenger Lists, 1850-1934. This guide will help you navigate the 500-plus roll collection of records and indexes.

You’ll find several different types of indexes, and the one you’ll use depends on when your ancestor emigrated. A Fifteen-Year Index covers the direct lists from 1856 to 1871. For the 1850s to 1870s, the Klüber Card File (Klüber Kartei) catalogs entries in both direct and indirect lists. Finally, Regular Indexes exist for the 1854 to 1934 direct lists and 1854 to 1910 indirect lists-but each year (or in some cases, part of a year) is indexed separately.

The voluminous amount of information on Hamburg emigrants doesn’t stop there. In addition to the actual passenger lists, the FSL offers indexed Hamburg passport applications (Reisepass) for 1851 to 1929, as well as residence (Meldeprotokolle) and citizenship (HeimatbÜcher) records for the 19th century (exact dates vary). As with the similar categories of records in Bremen, these records apply not only to Hamburg locals, but also the many emigrants who needed to earn money for their passages, and consequently stayed long enough to require registration as residents or citizens.

To find these records in the FSL catalog (start by clicking the link on the FamilySearch website’s home page), select Place Search, type in Hamburg as the place and Germany in the “part of” field, then click on the heading Germany, Hamburg, Hamburg. This brings up a long list of topics; look for passenger lists and passports under the Emigration and Immigration heading, residence records under Occupations, and citizenship rolls under Naturalization and Citizenship.

Checking Other European Ports

Of course, plenty of European emigrants came from ports besides Hamburg and Bremen. So what records can you expect to find, and where should you look for them?

As we take a peek at the pickings for Europe’s other primary emigration ports, remember that their governments generally tracked incoming foreigners more closely than outgoing citizens. In Britain, for instance, most pre-1890 emigration records documented “transports” — that is, prisoners being exiled for various offenses. Many of the records in this roundup are available on FSL microfilm; to locate them in the catalog, do place search for the port city’s name and look under the Emigration and Immigration, Occupations, and Naturalization and Citizenship headings.

British Isles

Ports such as Southampton, Liverpool and London, England; Glasgow, Scotland; and Londonderry, Northern Ireland, sent off many immigrants to America. A smattering of records exists in the British, Scottish and Irish national archives.

Netherlands

Rotterdam, a favorite departure spot for 18th-century Germans, has a mixture of records (notary documents, shipping contracts) in its archives; the book Trade in Strangers explains where to find them. The three-volume work Even More Palatine Families contains transcribed embarkation lists for Palatines (Germans from Pfalz) who came to America via England in 1709. (The UK National Archives houses the originals). The FSL also has a number of microfilmed Dutch emigration lists.

Belgium

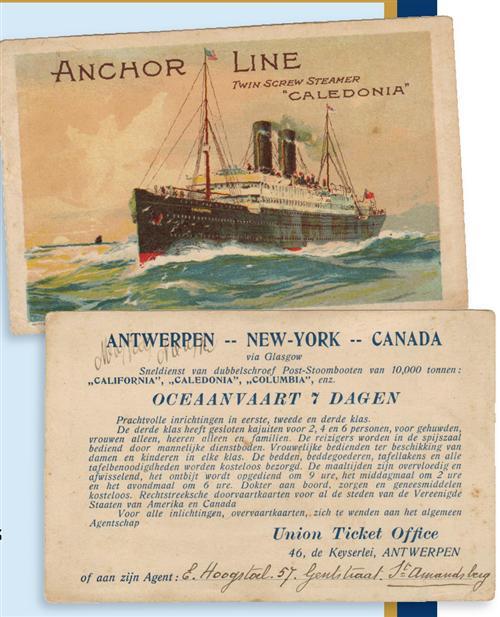

The port of Antwerp, popular in both the 18th and 19th centuries, kept detailed records, but the FSL has records only from 1855.

France

Although the French were one of Europe’s least migratory peoples, emigrants of other nationalities made Le Havre and Marseille important exit points. Le Havre’s archives holds some crew-member listings.

Italy

Unfortunately, few records are available from Italy’s four principal ports: Naples, Palermo, Genoa and Trieste (the latter served Balkan emigrants as well as Italians). A new emigration museum in Genoa houses that port’s records back to the early 1900s.

Scandinavia

Denmark, Norway and Sweden have perhaps the most comprehensive emigration records, most of which the FSL has microfilmed. Look for indexed documents for Bergen and Oslo, Norway, plus Stockholm and Malmo, Sweden. Various Scandinavian archives hold the rest. Wherever your immigrant ancestor set sail, don’t stop with the records generated on American shores. Documentation from the other side — the place where your forebear took those first pensive steps toward the New World — can help you understand the beginnings of his trip of a lifetime.

Researching Why Your Ancestors Left

Even if your ancestors didn’t leave an obvious paper trail at the port, you still can get a sense of the circumstances leading up to their departures. No matter which city or country they exited from, emigrants typically had to take certain steps before they left.

In the early years — before the abolition of serfdom — many emigrants still needed to buy their freedom from feudal allegiances, a process called “manumission.” For 18th-century emigrants from southwest German states, the works of Werner Hacker, who combed archives to find manumissions and other emigration documents, are vital.

Once tree of feudal obligations, early emigrants either walked or took riverboats to their port destinations. In these days of wind-powered sailing ships, emigration was tied to the seasons, with departures occurring in late spring through early summer in order to arrive by fall.

In the 1800s and 1900s, most emigrants still had to get a release of citizenship if they didn’t intend to return. But the situation changed dramatically in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when railroads sped up overland travel and steamships turned the Atlantic into a “superhighway”: Instead of planning permanent exits, many Europeans returned home after earning money in America. Sooner or later, though, a fair number of these migrant workers emigrated for good.

When emigrants reached their departure ports, they had to purchase their tickets if they hadn’t already. America’s “great wave” immigrants typically traveled in steerage; if they were strapped for cash, they might’ve worked in or near the port city till they could earn enough. In earlier times, poor emigrants would pay their passages by becoming indentured servants upon arriving in America.

Of course, because of the money involved — and in some cases, the need to prove military service — some emigrants left illegally. Those people’s journeys are predictably tough to track. But by understanding emigration history, you’ll get a picture of your ancestors’ departure.

Bremerhaven’s city archives holds Meldewesen — registers naming people who moved into or out of the area. Meldewesen go back as early as the 1850s, and like the aforementioned citizenship records, these documents primarily applied to people who needed to earn money before emigrating and therefore stayed in Bremen long enough to be registered (a minority of the total emigrants).

You can get all of these records from the appropriate archives by mail. When you request a search, supply as much information about the emigrant as you can: The more you know — name of the emigrant, birth date, name of ship — the better your chances for a successful search.

European Emigration Museums

American venues aren’t the only ones taking heritage tourism seriously these days: Two European port cities have emigration museums.

Embarkation goliath Bremerhaven hosts the Deutsches Auswandererhaus (German Emigration Center). Located on the site of the harbor from where 7.2 million German, Eastern European and Scandinavian emigrants sailed, the center allows visitors to experience the full cycle of emigration through text, visual and multimedia exhibits.

Museum goers also will learn about the port’s history. Bremen, founded in the 8th century and an important member of the medieval-era Hanseatic League, was built on the banks of the Weser River, 30 miles south of where the river emptied into North Sea. In the early 1800s, when the city fathers detected silt piling up in the bed of the Weser, they bought land near the river’s mouth from the King of Hannover, and built a new port — Bremerhaven.

In Genoa, Italy’s third-busiest passenger port, you’ll find the Emigration Study Center. Family historians can tap a database of embarkation records dating from the early 1900s, as well as see letters, diaries, photographs and the personal stories of emigrants and their descendants.

As many as 2 million people left via Genoa during the 1800s and early 1900s. That mass of emigrants transformed the port, turning it into one of Italy’s biggest cities. But the Galata del Mare museum in Genoa doesn’t look only at the past, it also seeks to bridge cultural gaps by highlighting the similar obstacles faced by yesterday’s and today’s emigrants. Visit the Memory and Migration exhibit at the Galata Museo del Mare to learn more.

A version of this article appeared in the February 2006 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: March 2024