Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Eating green vegetables. Flossing your teeth. Hitting the gym. These things are good for us, but that doesn’t mean we’re excited to do them.

To me, there’s no clearer family history equivalent of finishing your broccoli than citing sources. Creating accurate genealogy source citations can be dull and take lots of time, and—though they might acknowledge the importance of doing so—many researchers are unsure how they should start.

The good news is that, with reference books and online tools, adequately citing sources has never been easier. Citation is built right into the most popular tree-building tools, from Ancestry.com’s Member Trees to the RootsMagic desktop software. And services like EasyBib can generate citations for you in a variety of styles.

Let’s take a look at source citations: why you need them, what to include, and how to decide what format you should record them in.

Why Should You Cite Sources?

At a very basic level, source citations help someone viewing your research understand where you got your information. And you can cite all kinds of sources, from books to online records to interviews to emails.

In case you need some convincing, source citations will help your research by:

Adding credibility

Source citations “show your work,” demonstrating to others where you found information and how you reached your conclusions. This holds you accountable, disclosing your sources and allowing your readers to evaluate how reliable they are. This is particularly true if you’re hoping to publish research, or are seeking credentials from a body like the Board for Certification of Genealogists (BCG).

Re-tracing information

If you’re ever questioned on a fact or need to resolve conflicting details, citations give you a quick path to revisiting your documents. This will save you valuable time, especially when you come back to research after an extended period.

Identifying new records

By being intentional in documenting your sources, you’ll begin to notice if you’re overly reliant on one particular resource. This can be your invitation to seek out other resources to diversify your research, especially if (for example) you find you’ve only been using indexes and should seek out original records.

Giving credit where it’s due

Genealogy is all about collaboration. By referencing the websites, societies, archives, record collections and fellow researchers who have helped you along the way, you’re essentially saying “thanks”—plus acting as a referral to others.

Grounding your research

Well-formatted source citations are the same no matter where you’re working: online family trees, desktop software programs, or even a handwritten journal. As your work moves to new platforms or across multiple devices, your citations (if kept consistently) will help anchor your research.

The scholarly best practice is to cite any fact that isn’t common knowledge. Everyone knows that George Washington was the first US president under the Constitution, so you don’t need to cite a source when stating that. But how was his estate, Mount Vernon, laid out? And who was Washington’s next-in-command during the French and Indian War? Those details require research, and thus would need to be cited.

What to Include in Source Citations

The length and format of a source citation (including what details are in it) will vary based on the document or publication you’re citing. A citation for a government-created record, for example, will look significantly different from one for a printed book.

As a result, it’s crucial to study the source in question: where it comes from, when it was created and by whom, and how it’s being accessed. Researcher Shannon Combs-Bennett outlines the five basic details that a source citation should include, regardless of type of source:

- Who created the information (e.g., an author, an editor, a transcriber or a government)

- What the source is: the title (e.g., for a book) or a description of what kind of document the item is

- When the source was created and/or published

- Where in the larger work the information is (e.g., a page number)

- Where the source is (i.e., where it is physically or online)

Let’s look at an example. For a US passenger list, you’d want to include:

- Who: the US Department of Labor Immigration Service (which created the original record) or the National Archives (which houses microfilms of the record)

- What: a passenger arrival list, with a note about what format the list was viewed in

- When: the year the immigration took place

- Where in: the location of the list within the larger collection (e.g., the date, if the collection is organized chronologically), plus line number

- Where at: the name of the archive that holds the record (in this case, the National Archives and Records Administration), plus where you accessed the image

Note that last piece: In addition to type of source, your citations will also document how you accessed it—the format in which you viewed the source. So a citation for a passenger list will look different if you requested a copy from the National Archives versus viewing a microfilm at a library versus finding an image on FamilySearch.

In other words, if you viewed a digital image of a microfilmed passenger list on FamilySearch, you’d want to include information about the digital source as well as the physical source used to create it: what format the record was in, the website’s URL, and when you accessed it.

You might make additional notes to clarify how the digital source came to be. For example, many of the National Archives’ records have been digitized or otherwise made available by FamilySearch or commercial sites like Ancestry.com.

So the full source citation for a passenger list image viewed on FamilySearch might look like this:

“New York Passenger Arrival List (Ellis Island), 1892–1924,” roll 2945, volume 6740–6741, S.S. Rotterdam, 2 April 1921, line 8 (entry for Albert Einstein); digital image, FamilySearch (www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C95R-49LQ-T: accessed 3 June 2021); citing National Archives and Records Administration microfilm T715, Washington, DC.

Tip: When deciding how much detail to include in source citations, err on the side of too much. You can always strip out information depending on what style guide or format you’re publishing in.

How to Easily Format Source Citations

You may feel anxious approaching source citations because you don’t know what format to put them in. But take some solace in the fact that there is no single citation system that will work for all sources in all situations, nor one that should be used by all researchers.

You can certainly take advantage of tried-and-true templates. Elizabeth Shown Mills’ 892-page tome Evidence Explained: History Sources from Artifacts to Cyberspace (Genealogical Publishing Co.) is widely considered the gold standard of genealogy source citation, with samples for just about every resource you can think of. (Mills has great resources on her website, too.) Some publications or organizations will have their own style guides, such as the BCG Genealogy Standards or the Notes and Bibliography (NB) System of the Chicago Manual of Style.

But having said that, most genealogists can develop a system that suits their own needs. In fact, your source citation is effective as long as someone reviewing your research can successfully identify where you got your information.

Here are some quick tips for making your own source citation system:

- Create a document that explains your system and includes examples. Note-taking services like Evernote or word-processing programs like Google Docs can help.

- Use punctuation to separate items. Most systems call for commas or semicolons between data points, plus a period at the end.

- Create templates, especially for commonly used sources. This will help you quickly create consistent citations. (For example: Do you always include the full URL for a web-based source, or just the URL for the collection’s page?)

- Determine where you’d like to include citations. Do you have plans to publish your work? If so, make sure your system complies with the publication’s style guide or an industry standard like the Genealogical Proof Standard (GPS).

- Try to anticipate special cases. Prepare for scenarios where you’ll need to cite (for example) a whole family’s record instead of just one person’s entry.

- Anticipate missing information. Not all sources will have all the details you expect, so determine how you’ll handle situations in which you don’t have details like an author name or a page number.

- Borrow from existing systems. You don’t need to reinvent the wheel, so consider adapting standard styles for your own use rather than trying to build from scratch. Elizabeth Shown Mills outlines her system in Evidence Explained and in abbreviated form in Evidence! (both Genealogical Publishing Co.). It’s based in the Chicago Manual of Style.

Another factor to consider when developing your citation template: where you’ll be including citations, be it in research logs, online family trees, narrative histories, books, or even on paper copies of records themselves. The length and format will be dictated, in part, on how much space you have, and how you’ll be documenting sources in relation to the rest of the work (e.g., if you’re writing a narrative and want to cite sources in the text as you go).

In general, source-documentation will take one of three forms: in-text citations, footnotes/endnotes or a bibliography.

In-text

In-text, or parenthetical, citations are used to cite the source for a fact within the narrative of written projects. A citation (usually in some abbreviated format) is indicated in parentheses after the associated fact. A longer citation is generally included at the end of the work in a bibliography (see below).

Footnotes

Footnotes or endnotes also refer the reader to a source from within text, but via a superscript and to a citation somewhere else in the document. At the bottom of the page (in the footnote) or at the end of the document (in the endnote), you cite your source in full. If you reference the same source again within a project, you may not need to include the full citation; many style guides allow for abbreviated citations upon second (and further) reference. This is considered the most thorough method, since it allows you to link full citation directly to facts.

Bibliography

A source list (or bibliography) simply compiles all your sources in one place, usually sorting them alphabetically by author or title. Each listing in a bibliography will closely resemble the first-reference footnote/endnote citation, but there may be differences in how information is organized.

Sample Source Citations

As you can see, making a citation requires you to learn quite a bit about where a source comes from. Here are a few more examples:

So, editor’s orders: Make source citations as you go. They won’t help you lose weight, build strong bones or prevent gingivitis, but they might just save you some heartache.

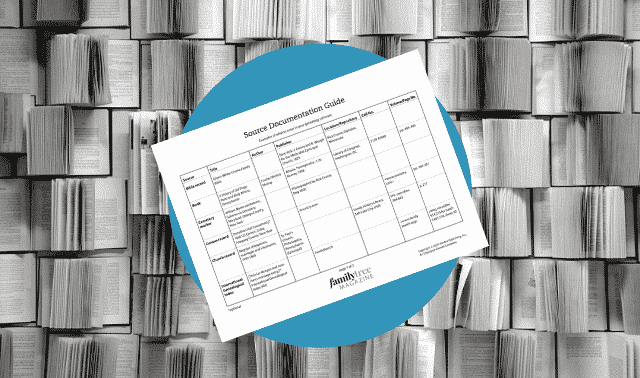

Tip: Here’s a quick source citations guide from genealogy expert Shannon Combs-Bennett for you to use:

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the September/October 2021 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated January 2025.

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program and an affiliate program through Genealogical Publishing Co. It provides a means for this site to earn advertising fees, by advertising and linking to affiliated websites.