Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Built over the site where ships arrived with thousands of chained Africans, a new museum in Charleston tells the stories of people and places shaped by the international slave trade. The museum, called the International African American Museum (IAAM), opened in June 2023 and includes a Center for Family History where visitors can trace their African American ancestry.

Here’s a closer look at the IAAM: its history, and its promise to tell the stories of those whose tales previously went untold.

A Museum Decades in the Making

Built over decades in the late 1700s, Gadsden’s Wharf in Charleston, SC, measured 840 feet long and held six ships at a time. Local merchant and slave trader Christopher Gadsden completed the wharf on Charleston Harbor along what was Wharf Street, flanked by what are now Calhoun and Laurens streets. Some historians estimate that nearly 100,000 Africans were taken off ships there between 1783 and Jan. 1, 1808, when Congress banned the import of enslaved people into North America.

In February, 1806, Charleston’s city council mandated that all slave ships had to land at Gadsden’s Wharf, then located just outside the city. Seeing the ban on the horizon, importers rushed to do all the business they could. According to The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, about 200 ships crammed with 30,000 chained Africans arrived during those two years.

Up to 90 percent of today’s African Americans have at least one African ancestor who arrived in America at Charleston, making it a kind of Ellis Island to their descendants. Harvard professor and “Finding Your Roots” television series host, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., has called the city “ground zero of the African-American experience.”

In 2014, timbers, bricks and other remnants of the once-forgotten wharf were discovered under an empty grass lot. More than 200 years after importing slaves became illegal in America, that lot became a fitting home for IAAM, a museum that remembers the enslaved humans traded there.

Why Charleston?

No records detail voyages of slave ships. Instead, researchers who built The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database rely on unpublished sources such as captain’s logs and newspapers in dozens of languages from libraries all over the world. They’ve estimated that about 388,000 enslaved Africans were transported directly to North America during the Middle Passage—the stage of the triangular trade when slaves were shipped west across the Atlantic. This represents a fraction of the total number of humans shipped to the New World, estimated at 12.5 million between 1525 and 1866.

South Carolina received more Africans than any other mainland colony. As many as half of Africans brought to America were disembarked at Charleston. Rice had become the dominant crop in the hot, marshy coastal Low Country. Planters there sought Africans primarily from the “Rice Coast” region of West Africa, also known as the Windward Coast. It’s now Senegal, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia. West Africans had been growing and processing rice for centuries, and they drew high prices from planters wanting to transform coastal wetlands into fields of “Carolina Gold.” Free African labor and profits from rice made Charleston the richest city in British North America after 1700.

Up to 90 percent of today’s African Americans have at least one African ancestor who arrived at America in Charleston.

Weak and ravenous from the voyage across the Atlantic Ocean, many of the enslaved Africans were brought first to Sullivan’s Island, at the entrance to Charleston Harbor. A 1744 law required slaves be quarantined there in a “pest house” (short for pestilence). Once a doctor cleared them, they were brought into the city.

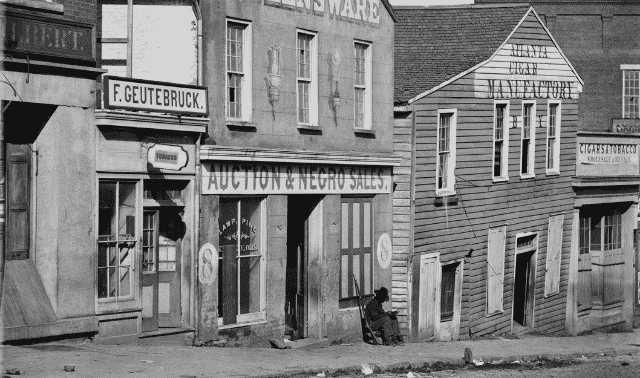

The enslaved men, women and children at Gadsden’s Wharf were stored in subhuman conditions in warehouses, awaiting auction. It’s believed that during the frigid winter of 1807 to 1808, nearly 800 Africans froze to death. On March 5, 1800, visitor David Selden wrote to his parents in Connecticut, “I cannot but reflect on the awful sight to be seen at a place called Gadsden Wharf of about four thousand poor Africans naked in a manner and lousy. The most distressing sight I ever beheld, offered for sale every day at auction to him who will give the most.” (Selden’s letter is now at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.)

A Place to Remember

Former Charleston Mayor Joseph Riley, Jr., proposed an African-American history museum during his 2000 inaugural address. He called the project his “most important work” in the New York Times. It would be expensive: The price tag for the 40,000 square-foot museum was estimated at $100 million. Three-quarters of the total would have to be raised before construction could begin.

Riley’s vision garnered financial support from local governments, Charleston business owners, national organizations and historians. The city of Charleston provided $12.5 million plus the riverfront real estate where Gadsden’s Wharf once stood. The county pledged $12.5 million; the state of South Carolina, $25 million. The Charleston Naval Complex Redevelopment Authority committed $11 million. Hundreds of private donations totaled more than $25 million, including $10 million from the Indianapolis-based Lilly Endowment philanthropic foundation.

By August, 2018, the goal had been surpassed. “Setting a $75 million goal was monumental, and many thought it was impossible,” Riley said during a celebration at the Charleston Maritime Center. Construction began in early 2019, with a grand opening planned for 2020. (Plans had to be delayed because of the COVID-19 pandemic.)

The IAAM also received a donation of 2 million dollars from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 2019. In a FamilySearch blog post, Elder David A. Bednar said, “We want to support the museum and the Center for Family History because we both value the strength that comes from learning about our families. The museum will not only educate its patrons on the important contributions of Africans who came through Gadsden’s Wharf and Charleston, it also will help all who visit to discover and connect with ancestors whose stories previously may not have been known.”

Other contributors include Vivid-Pix, which donated several of its Memory Station document-scanners to the Center for Family History.

The museum, designed by architectural firms, Pei Cobb Freed & Partners and Moody Nolan, is raised on pillars. The elevation respects the sacred nature of the wharf ground. A line will demarcate the wharf’s location, and a garden and memorials will remember the transported humans. Museum balconies will offer a view of Charleston Harbor and a place to reflect on the lives of African ancestors forcibly brought there.

The IAAM website gives you a peek at eight exhibition “districts” that take visitors on a journey from the 17th century in West Africa to present-day nations and communities shaped by the transatlantic slave trade. Visitors will get a comprehensive, unvarnished look at African and African American history, and its place in American history. Expansive television screens will feature a panoramic video that virtually takes visitors across Atlantic ports, displaying landscapes, people and communities.

A gallery will be devoted to the Gullah-Geechee people, descendants of slaves on the rice fields of coastal Carolina, Georgia and Florida. They built a language and culture that blended their diverse African backgrounds with American and American Indian influences. African cultural and linguistic retention were stronger here than anywhere else in America. A social action lab will host forums, seminars and training programs on current issues. Plans also include a multipurpose community room, a gift shop, a café and a multimedia theater.

Exploring Ancestor Stories

Almost all Americans have roots somewhere else. Many genealogists want to identify that place—the overseas town where a family originated.

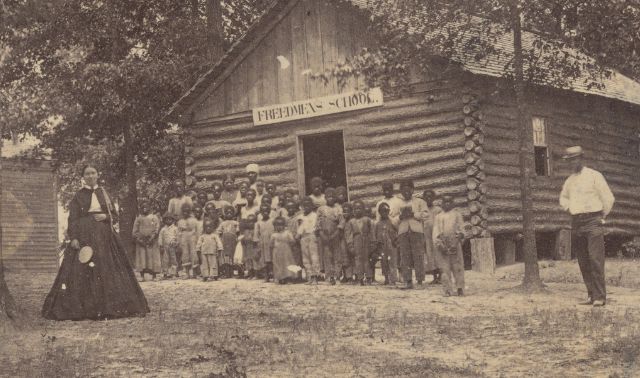

But the horrific nature of slavery makes it virtually impossible for African Americans to find a paper trail leading to a place and tribe in Africa, let alone the birth names of African ancestors brought to American ports. Even tracing Africans in the United States before the 1870 census is particularly challenging, requiring extensive exploratory research in court records and other sources of the slaveholding families.

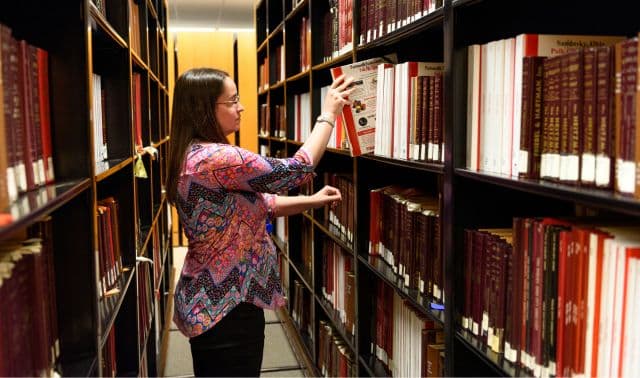

One of the IAAM’s biggest draws will be its Center of Family History, where visitors can get help tracing their African American families in on-site research collections. It’ll carry out the museum’s mission on a personal level, helping people discover the roles their own enslaved ancestors played in molding American history.

Toni Carrier, founding director of the Lowcountry Africana Project, is leading the center’s development. “There are many legacies of slavery we can do nothing about,” she says. Not being able to learn the names and life stories of enslaved ancestors does not have to be one of them.”

Carrier wants to provide an intimate genealogical experience for researchers desiring to relate their family histories to Charleston and Gadsden’s Wharf. “The records do exist, and trained, experienced research assistants at the center will be able to help connect descendants with records of their ancestors.”

Most African Americans descend from Western African ethnic groups such as the Fula/Fulani, Gola, Kissi, Mende, Mandinka, Temne and Vai. Carrier plans help for those wanting to use DNA to connect with a place in Africa: selecting DNA tests, understanding results, and using them to uncover lost family history. A Story Booth stands waiting to record oral histories, interviews with family, and thoughts on the museum.

You can visit the center’s website for advice from professional genealogist Robin Foster, and digitized marriage records, newspaper clippings, and more. Carrier’s pre-opening projects focus on genealogy education and gathering resources such as African American family histories, photos, US Colored Troops pension files, and more.

The 1870 US census records Africa as the birthplace for at least 15 individuals living in Charleston County that year, five years after the Civil War ended. Their names include Betty Angel, Jack Bright, Frank MacBeath and 109-year-old Ben Fraser, whose birthplace was more specifically noted as Liberia.

In all of South Carolina, the 1870 census notes more than 150 others born in Africa. Many resided in the Low Country. George Backus of Darlington County, Hagar Caleb of Beaufort County, Thomas and Rebecca Jackson on James Island, Renty Johnson of Richland County, Jack Sims of Union County, Hannah Walker of Orangeburg County and other Africa-born freedmen had survived the journey across the Atlantic and slavery in America.

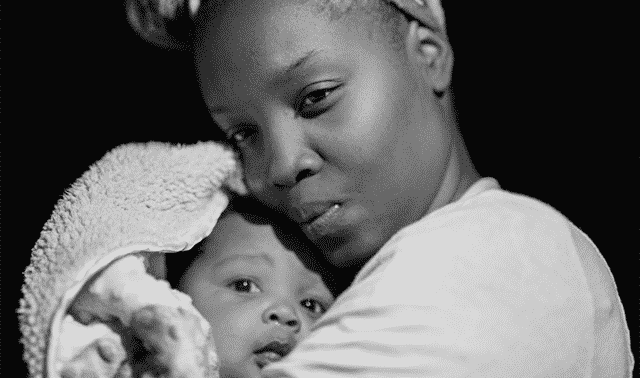

Though a lack of records of slave ships’ human cargo means we can’t know for sure, history tells us they quite possibly experienced Gadsden’s Wharf, filled with grief for their homelands and fear for their futures. The IAAM will tell their stories; they are no longer forgotten.

A version of this article appeared in the January/February 2019 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated in June 2023 to reflect the museum’s opening.