Nancy Bane troubled me. And Delia Gordon will always be a thorn in my side. These are two of the women of the past I’m researching, and one of them isn’t even my ancestor. I happened to stumble upon Nancy in records while I was looking for one of mine; yet her life intrigued me and yearned to be told.

Do you have your own Nancy or Delia, women whose stories remain tantalizingly incomplete? Do you have female ancestors on your pedigree chart for whom you don’t have a maiden name? Or perhaps you have female ancestors for whom you don’t know the names of their parents. Maybe you have female ancestors missing a first name, not to mention a maiden name and parents. You’re not alone; we all have them.

Leading private lives

Your female ancestors are simply tougher to trace than the men in your family. Their maiden names disappeared with their marriage. Their roles in history have been less celebrated and less recorded. Women led private lives, unlike their husbands who led public lives. Men served in the military, they bought and sold land, they sued and were sued, but women had few legal rights until the late 19th and early 20th century. When a woman married, everything she owned became her husband’s, even the clothes on her back. Unless she remained single or was widowed or divorced, she couldn’t enter into any legal contracts without her husband’s consent, whether it was writing a will or buying or selling land she inherited from her father. Even the legal custody of her children belonged to the father.

But that doesn’t mean you should give up — or that you should be satisfied with finding your female ancestors’ maiden names, or their parents’ names, or when they were born and died, or that they gave birth to several kids. I want to know everything I can about my Nancy and Delia, their families and their lives.

Let’s look first at ways to find maiden names and parents’ names, then explore how to breathe life into that woman’s name on your family tree.

Exploring basic records

Let’s use Nancy Bane as an example. Nancy was silently waiting for me to discover her on the 1880 Ohio federal census in Gallia County. She was 62 and living with her husband, 61-year-old Henry D. Bane, and their son, 29-year-old William. What caught my eye was the tick mark under the column for insane persons in Nancy’s entry. Further research revealed that she’d been a patient at the Central Ohio Institution and had 24 attacks of “mania,” beginning at age 47. She was discharged in 1868 when she was about 50. How intriguing. Who was this woman? Suddenly, I wanted to know everything about her.

Whether you’re researching a mystery like Nancy or any other ancestor, male or female, you need to start by covering all the basic records:

- Check all the federal censuses for the person’s lifetime.

- Look for vital records, such as births, marriages and deaths.

- Seek possible published family histories.

- Scour published abstracts of records for the area in which you’re searching.

These are, of course, the comparatively easy things to do, and one of them may hold the answer you’re after. Since I was at the Family History Library in Salt Lake City, I had convenient access to a variety of published and microfilmed sources for Gallia County, Ohio, where Nancy Bane lived.

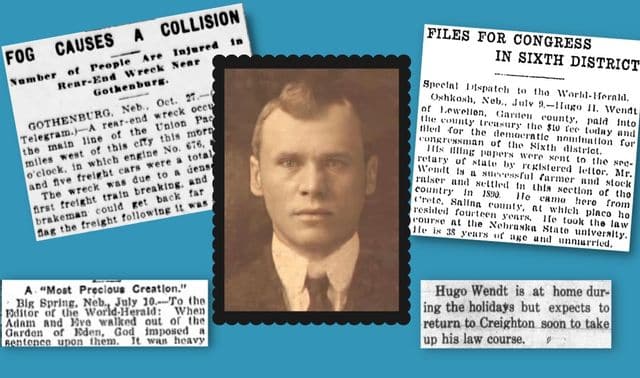

Researching death records

Unfortunately, Nancy died before deaths were routinely recorded in Ohio, but I did find a death notice for her in a newspaper. It didn’t give me any information about her maiden name or her parents. I next checked for a marriage record and found that in 1842 Henry D. Bane married Nancy Donnally. Bingo! This was likely her maiden name, but there was a possibility that Nancy had been married before she married Henry, so this could be her married name by a first husband. It’s important to confirm information from several different sources before reaching a conclusion.

Going on the assumption that Donnally was likely Nancy’s maiden name, I wondered if someone with the last name of Donnally had died in Gallia County and named a daughter Nancy Bane in a will. In a published abstract of wills for Gallia County, none of the wills made by people named Donnally referenced a daughter Nancy Bane. In the 1855 will of Andrew Donnally, he named a daughter Nancy Donnally, but this Nancy had been married 13 years by the time this will was signed. It’s unlikely that a father would still refer to his daughter by her maiden name — no matter how much he might have disliked her husband — 13 years later. So I kept looking.

Researching court records

In a book of abstracted chancery court records for Gallia County, I found a case involving Henry D. Bane and his wife, Nancy, with a John A. Donnally — a land foreclosure dated Oct. 18, 1851. OK, so who was John A. Donnally? Was he Nancy’s father? Now my search turned to this man, and I found a court case involving John Newton vs. John A. Donnally back on May 14, 1840. According to the abstract, a William Donnally conveyed land to his children to defraud Newton. The children of William Donnally were named in the document:

John A. and Nancy, who were of full age, and William Jr., Eleanor, Sarah, Mary Ann, Philip J., Martha, Reuben G. and Marinda, all minors. Hmm. Looks like John and Nancy were siblings and William was their father. But is this Nancy Donnally the same as Nancy (Donnally) Bane?

The published abstracts contained two other significant cases, which I confirmed in the microfilm of the original documents. One involved John A. Donnally again and a Sarah Donnally. Sarah was identified as the widow of William Donnally, who’d died Jan. 1, 1847. The other case concerned John Newton, administrator for William Grayum, vs. James Grayum, Reuben Grayum, John Grayum, Sarah and William Donnally, Martha and Randall Russell, Mary Ann and Noah Wood, and Rachel and John Swindler. This 1839 case revolved around William Grayum, who died without a will, and the need to sell his property to pay his debts. The people named were the sons and married daughters of William Grayum.

Using cluster research

Historian Elizabeth Fox-Genovese said that the “history of women cannot be written without attention to women’s relations with men in general and with ‘their’ men in particular, nor without attention to the other women of their society.” From a genealogical research standpoint, we might say the same thing. Those who successfully find the maiden names and parents’ names of female ancestors aren’t focusing their research efforts on just the woman in question. They’re also researching the woman’s husband and every person he comes into contact with.

For Nancy, I found her husband linked to John A. Donnally, who shared Nancy’s probable maiden name. I then looked for him, and sure enough there was an important clue: He was the son of William Donnally, and had a sister named Nancy. Now I was on the trail of William Donnally as well as John A. Donnally to see if there were more records to confirm their connections with Nancy. In looking for records of these two men, I found William was married to a woman named Sarah Grayum.

Researching the census

In the 1850 federal census, I found John A. Donnally, and living in his household was a 25-year-old woman named Elizabeth Bane, born in Virginia. Nancy’s husband, Henry D. Bane, was 31 in 1850, and he was born in Virginia, too. Living next door to John was a Sarah Donnally, age 51, with 15-year-old Martha Donnally. If this is John’s mother, which it certainly must be, it would make sense that she would be living without a spouse in 1850, since her husband, William, had died in 1847. Sarah is living with Martha — likely her daughter — and there was a Martha listed as a minor daughter of William Donnally in 1840. Notice how the same names keep cropping up in these records? Emily Croom, in The Sleuth Book for Genealogists (Betterway Books), calls this “cluster genealogy.” Families and close friends tended to cluster together, not only in living proximity, but in the records, too.

At the Family History Library, I had exhausted all of the available Gallia County records. While my research strongly suggested that Nancy Bane was more than likely the daughter of William and Sarah (Grayum) Donnally, I wondered if there might be other I records to confirm her identity that I didn’t have access to. I made contact with a helpful researcher at the Gallia County Historical Society in Gallipolis, Ohio. She discovered a record for me — and it is the only one uncovered so far — that specifically states who Nancy’s parents were. On a funeral home register held at the historical society, it named Nancy’s parents: William and Sarah (Graham) Donley (sic). My research efforts had been on the right track.

Some female-ancestor mysteries are easier to solve than others, but there’s no magic bullet. It takes diligence and persistence, and you have to exhaust all the records in the area where a woman lived. In particular, you must broaden your research to the men she was connected with, simply because men left more records.

As you can see, women no longer have to be kept in obscurity in a family history. If you thought you’d done all you could in researching about your female ancestors, think again. Remember, half of all of your ancestors were women, and most are waiting silently for you to tell their life stories. Don’t let their legacy be just a name on a chart.

Nancy Bane no longer troubles me. She “spoke” up in the records, allowing me to document her life. As for Delia Gordon, well, if she’d just speak above a whisper and tell me when she came to America, I’d be happy.

A version of this article appeared in the the April 2001 issue of Family Tree Magazine

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in the Genealogical.com Affiliate Program, affiliate advertising programs are designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to affiliated websites.