Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

NOTE: Most material adapted from articles written by Claire Santry.

Maybe you have ancestors who arrived in America from Ireland during one of the major immigration waves between 1850 and 1900. Maybe your relatives have lived in the lush island nation for generations, and you are ready to embark on a journey to learn more about them. Despite its small size, Ireland is a hardy nation that has undergone religious strife, famine and other hardships over the course of its history. Fortunately, we boast many guides to help you discover your Irish roots. Below are some resources to get you started.

Understanding Irish History

Before you dive deeply into your Irish heritage, you might benefit from understanding some historical context. These events can help explain why your ancestors might have left Ireland for other places or at least illustrate how Ireland became what it is today. Below is an overview of some of these events:

The Protestant Reformation (1600s): Due to Ireland’s strong strong Roman Catholic influence, the Protestant Reformation that swept across Europe in the 16th century generally failed in Ireland. That said, by far the largest religious group across Ireland, Roman Catholics were hit hard by Penal Laws following the Reformation and establishment of the Protestant Church of Ireland.

The Flight of the Earls (1607): Marked the departure of Irish earls Rory O’Donnell and Hugh O’Neill from Rathmullan, Ireland to mainland Europe. Event believed to define the end of the Gaelic order in Ireland.

Plantation of Ulster (1609): When the Ulster province of Ireland was colonized in an effort to bolster the British Monarchy and promote Protestantism.

The Cromwellian Conquest (1649–1653): Time during which the English took control and Oliver Cromwell seized Roman Catholic land.

The Battle of the Boyne (1690): As its name suggests, this conflict was fought between King James II (Catholic) and King William III (Protestant) near the River Boyne

The Penal Laws (1695-1790s): These laws severely limited the rights of Catholics in Ireland and ensured Protestant control

The Great Famine (1845–1851): Failed potato crops severely decimated Ireland’s population due to starvation and mass emigration

The Land War (1879): A period in which tensions rose between farmers and landlords, by which farmers demanded more robust rights and reasonable rent prices

Partition (1921): This event marked the division of Ireland into Northern Ireland and what we know now as Ireland today

Independence from Great Britain (effective in 1922)

Finding and Using Irish Genealogy Records

Because Ireland is an English-speaking country, you may not face the same barriers that often arise when uncovering records from elsewhere in Europe. Still, finding the records you seek and making sense of them can take time. Below we provide some examples of records you are likely to come across as you research your Irish heritage.

Civil Records

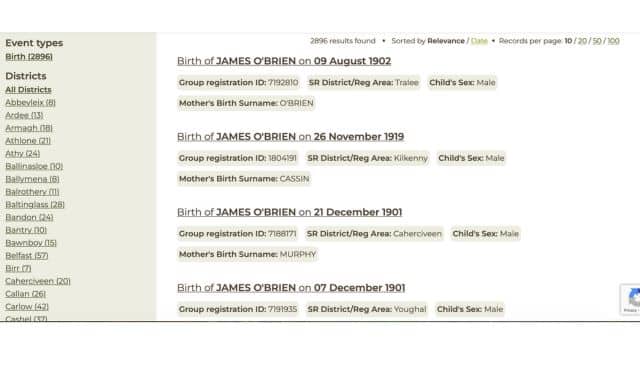

In Ireland, civil registration of all births, deaths and marriages was officially introduced in 1964; however, you can find records from non-Catholic marriages starting in 1845. As you explore your Irish heritage, you will likely hear about the fire in 1922 that ravaged the Public Record Office in Dublin. While devastating, the fire did not completely out vital genealogical records. Civil registration records remained largely unscathed. It also helps that Ireland has prioritized digitization efforts for its civil records system. You can explore FamilySearch’s collection of Civil Registration Indexes from 1845 to 1958. IrishGenealogy.ie also allows you to search and peruse civil records.

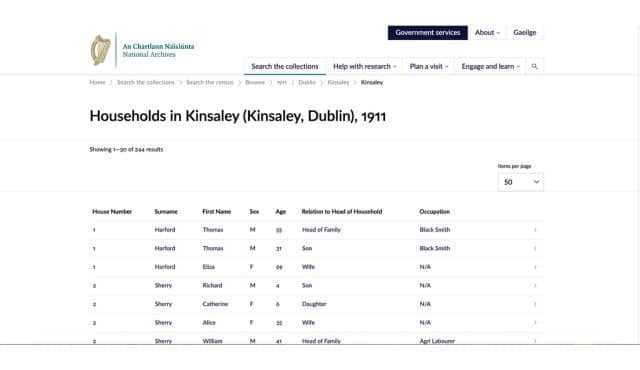

Census Records

Unfortunately, most of Ireland’s census records were destroyed in the fire mentioned above; however, the 1901 and 1911 censuses survived and are available to search for free on the National Archives of Ireland website. Census records can reveal a good deal about your Irish ancestors—occupation, county or country of birth, religion and more. For pre-1901 records, the National Archives of Ireland allows you to search here.

Church Records

The availability of Irish church records varies by denomination and time period. Below is an overview of some of these records and where you can find them.

Roman Catholic

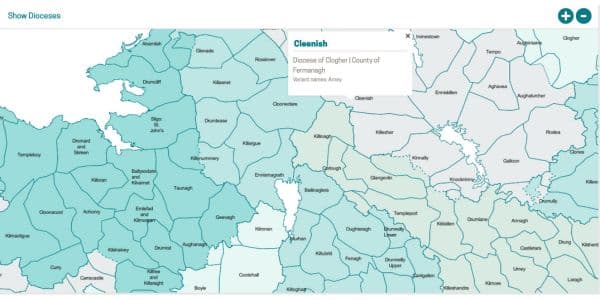

Following the Reformation and the establishment of the Protestant Church of Ireland, Penal Laws restricted Catholic churches from keeping records without risk of severe punishment. Therefore, your hunt for baptism, burial and marriage records may be difficult. This is especially true since most immigrants came from the west and north of the island, regions for which you won’t find registers until the mid-19th century. In any case, you can search all surviving Catholic registers for free via the National Library of Ireland website. You can enter a parish name or search the handy map provided (pictured below), which allows you to zoom in and out.

Another major collection, typically spanning into the 1920s or later, is held at RootsIreland. This covers most of the island. For any gaps in information, records can also be found at www.irishgenealogy.ie.

Church of Ireland

As the Established Church after the Reformation, the Church of Ireland was to keep records of Protestants. While some early registers survive for urban parishes, the majority date from the late 18th or early 19th centuries.

The Church of Ireland’s archive is held by the Representative Church Body (RCB) Library in Dublin, which holds most of the parish registers that were not destroyed in the PRO fire of 1922. It publishes a useful and regularly updated List of Parish Registers, identifying those that were lost and detailing where you can access surviving records online and offline. Download the PDF.

You can browse the Anglican Record Project via the Church of Ireland website. The project is still growing, but you may be surprised by what you find. You can also search the IrishGenealogy.ie website for church records.

Other church records may include:

- Presbyterian: Offline, PRONI has microfilms of nearly all surviving registers, while the Presbyterian Historical Society of Ireland holds a small and exclusive collection.

- Methodist: Until the 1820s, the records of Methodists are usually found in the registers of their local Church of Ireland church. A handful of Methodist-only registers date from 1815, but most start in the 1830s to 1840s. RootsIreland has some transcribed records, and PRONI has a large microfilmed collection. For more details, contact the Methodist Historical Society of Ireland.

- Quaker: Most Quaker records of births, marriages and deaths date from the 1670s. Subject to the 100-75-50 year privacy rule, the collection is accessible to subscribers of Findmypast. Learn more details.

Griffith’s Valuation

Griffith’s Valuation was a property tax survey conducted between 1848 and 1864, and the records it produced may prove useful to you as you research your Irish genealogy. Anyone who owned or leased land is included in this survey, covering roughly 80% of the population. You can search Griffith’s Valuation for free on the Ask About Ireland website.

Tithe Applotments

The Tithe Applotment Books (1823 to 1837) are arranged by parish and recorded those who rented or worked agricultural land (except church lands). If your ancestors lived in urban areas or did not work on the land, they won’t have been included. However, if your ancestors lived in a rural parish for which no pre-1850 church registers exist, this collection may hold the only documented record of their lives. The National Archives has online versions of the books that are free to search and view; the books for Northern Ireland are free at PRONI.

Headstones

The transcription of headstone inscriptions, which often reference names, dates and places, is not new or unique to Ireland. But it has become very much a group activity in recent years. Most of the resulting record sets are now online, but they are scattered across the Internet, at both free and subscription sites. For a summary, see this free list.

Newspaper Obituaries

The day digitization of newspapers became possible was a game changer for family historians around the world. While a newspaper death notice may provide perfunctory information, an obituary or funeral report often provides a wealth of detail, including place of origin and residence. For Irish obits, try the Irish Newspaper Archives, the British Newspaper Archive (its 200+ Irish titles are also at Findmypast), and, from 1859, the archive of The Irish Times newspaper.

Understanding the Geography of Ireland

While it is certainly critical to conducting thorough genealogical research, parsing your Irish ancestors’ records is just one piece of the puzzle. You may also benefit from understanding the political and geographic landscape of Ireland over the years and how this could have shaped your ancestors’ lives. Below are some strategies for exploring maps of Ireland to better help you pin down your ancestors.

Before you explore said maps, it might help to understand the six historical jurisdictions:

- Barony: You won’t see the barony mentioned in modern Ireland, although you may come across records that mention the term. Old land records, surveys and early censuses are examples of such records.

- County: The country of Ireland is made up of 32 counties. You will find many records organized by county.

- District Electoral Division: Organize voting by place of residence. Also used for census record collection purposes.

- Parishes: Both the Catholic Church and the Church of Ireland use parishes for administrative purposes, although their boundaries can vary.

- Poor Law Union: From the late 1830s, Poor law unions (PLUs) were formed from groups of civil parishes as local-government administrations centered on market towns. With the establishment of the General Register Office in 1864, PLUs became Superintendent Registrar Districts, the divisions responsible for documenting civil registration of births, marriages and deaths.

- Townland: the smallest geographic designation. It is important to note that there are many townlands that share the same name.

Understanding these terms can make finding, reading and analyzing records a much more straightforward process.

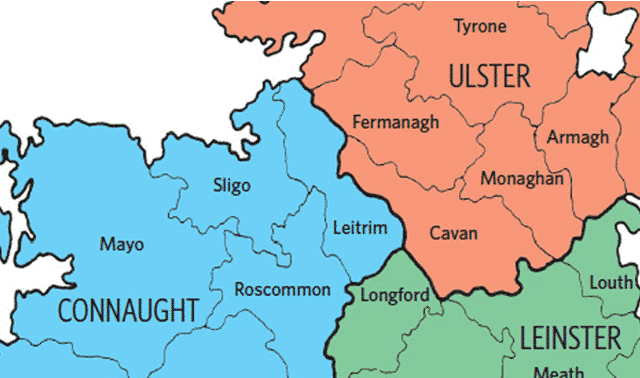

Map of Irish Counties

You will want to determine what county your ancestors hail from, as much administrative business occurred on the county level for most of Ireland’s history. The country is divided into 32 counties. This map can help you visualize these counties, as well as the four provinces they historically comprised.

Poor Law Unions Map of Ireland

As mentioned above, poor law unions (or PLU) are distinct geographic regions designated by the British government to aid the poor. Poor law unions no longer exist; however, many records mentioning them endure. Determining the union in which your ancestors lived can help you uncover some key information, including birth, death and marriage.

Map of Ireland Before the Great Famine

The Great Famine significantly shaped Ireland. It killed around one million people due to starvation and led to the emigration of roughly one million more. At one point, more than half of immigrants in the United States hailed from Ireland. You can find a map of the country before the Great Famine here.

Locating Scots-Irish Ancestors

The Scots-Irish are ethnic Scottish people who settled in the Ulster counties of Ireland before arriving in the United States in the 18th century. Several million Americans are proud to call themselves Scots-Irish. The Scots-Irish did not create the number of records that other immigrant groups had; however, there are still many tools available to help you track down your ancestors and strategies to help you overcome any potential brick walls in your search.

- Consult Land Records: The Scots-Irish cherished land ownership. With that in mind, you might be able to uncover information about your ancestors by searching for land records. Try deed indexes, but don’t just limit yourself to when your ancestors lived in a given area. You might even analyze more recent deeds that can point you in the direction of transactions that were never recorded.

- Don’t Overlook Census Records: As mentioned above, the 1901 and 1911 censuses are free to search via the National Archives of Ireland. It may be tempting to overlook these censuses, as most Scots-Irish had emigrated to the United States after these censuses were taken. However, they may still be worth perusing, as you could potentially uncover family members who did not leave or even our ancestors’ place of origin.

- Explore Websites, Organizations and Other Resources: The Scots-Irish might not have been meticulous record keepers; the good news is that there is no shortage of resources and records to help you find the information that you need. For example, websites like the Ulster Historical Foundation offer free-to-view collections like “Graveyards in Ulster.”

Irish Genealogy Websites

We have already mentioned several websites above. As it turns out, there are many other websites that can guide you on your Irish genealogy journey. These websites can help you locate records, provide useful downloadable guides and more. Some of the most popular sites include:

- GENUKI: A quick search with the handy the GENUKI Gazetteer can yield online maps and place names so that you can more easily pinpoint the records you are looking for. Also use the church directory to locate churches and cemeteries.

- IrishGenealogy.ie: Search church and civil records for free.

- National Archives of Ireland: This is the website for searching census records (1901 and 1911) and any other census records that have survived over the years. You can also search court records, will registers and more.

- National Library of Ireland: Peruse collections containing a total of over 12 million items, including newspapers, photos and maps. Also be sure explore the Catholic Parish Registers.

- Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI): Search a range of valuable collections, including early wills, street directories and maps.

- RootsIreland: This website boasts over 23 million records across 34 county genealogy centers in Ireland. Find a wealth of church records, including marriages, burials and deaths. Also find census records and census record substitutes and Irish ship passenger lists.

- Virtual Record Treasury of Ireland: At the start of the Irish Civil War, the Public Record Office of Ireland was destroyed in a fire. The Virtual Record Treasury is an effort to recreate what was lost. With over 50 million words of manuscripts and text records, you can easily spend hours exploring the treasury’s offerings.