Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

If you have McAlpines, Hamiltons or Leslies in your family tree, you may have studied Scottish records and dreamed of finding them and their cozy cottages or stately homes. But in reality, you’ve maybe looked in the wrong place—or, more accurately, in the right place but at the wrong time.

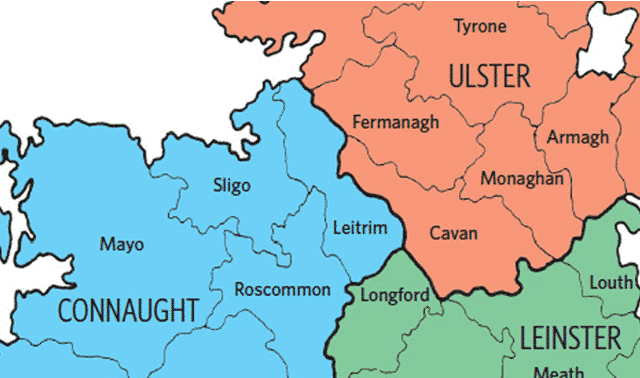

A great many of our ancestors who have Scottish surnames actually were part of a community of Scottish emigrants who settled in the north of Ireland generations before their descendants came to America: the Scots-Irish. These were descendants of Protestants from Scotland and England who populated Ulster (the northernmost province of Ireland).

More than 1.5 million Ulster Scots left Ireland between 1718 and 1890, and many thousands of them arrived in the American Colonies before the Revolutionary War and loomed large in American social and cultural history. Many were Scots from Ayrshire or other Lowland counties, and indeed migrants are typically assumed to have been Protestants with ancestry from Scotland. But Protestants from England and France also settled in Ulster. Other “Ulster Scots” were actually native Irish, and still more intermarried—all complicating the standard story line of the “Scots-Irish.”

Despite the important roles these Scots-Irish played in the settlement of America, they can be difficult to trace. The first challenge is that your ancestral hometown—the most important detail for research—is difficult to find for those who have families from Ulster (especially if they came to North America in the 18th century).

In addition, Irish records can be hard to find—if they exist at all. Many documents you’d expect to find from the old country weren’t kept (or weren’t taken care of). And even if they were, the 1922 Four Courts Fire in Dublin destroyed many of them. Experts estimate that most people won’t be able to take their family research beyond the 1800s, when church records typically began. And because many people’s Scots-Irish ancestors came to America beginning in 1718, researchers will be starting their research in Ireland about 100 years beyond what most Irish genealogists say is possible!

As a result, Scots-Irish research requires a lot of patience and luck. While the search is worthwhile and rewarding, you’ll likely face a dead end in your research earlier than you’d wish.

Do you know where to look for your Scots-Irish ancestors? These resources might have the information you’re looking for.

Scots-Irish Genealogy Websites

Because Irish records are often scarce, those researching ancestors from Ulster have their hands full.

Fortunately, many online sources will provide you with a path through the rough terrain of Scots-Irish history. Some of the following websites have records in which you may find your ancestor, while others will help you identify their townland or improve your research skills. Even if you can’t learn their names, you can definitely learn about their homes and their historical times when armed with the following websites—and a right-sized set of expectations.

1. Family History 2016

Named in honor of the 100th anniversary of the Easter Rising in 1916 (a pivotal moment in the Irish independence movement), Family History 2016 provides family historians with tools to research their ancestors. The Family History 2016 project has seven modules (lessons): surnames, place names, census records, civil records, church records, property records and military records. Each module provides historical background as well as information on how to find and use the records. You can also access links to records themselves. Be sure to check out the two case studies.

2. Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI)

The Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI) has custody of private papers, church records and other documents that span 400 years of Irish history. This government office’s website details what’s available online; a growing collection of digitized church records is only available in-person in Belfast. Keep in mind that most are derived from copies of records—many originals no longer exist. (And even surviving records no longer exist in their entirety.)

Be sure to carefully read the details of each record set so you know what to expect:

- The Freeholders’ records include lists of who owned land outright or held it on life-lease. Because ability to vote was tied to land-ownership, you should search for voter records for ancestors you find here.

- The Name Search is a combined index that includes pre-1858 wills and surviving portions of religious censuses and dissenters petitions from the 18th century.

- The Street Directories collection has volumes dating back to 1819. Some directories include listings from just Belfast, while others include the rest of Ulster as well.

- The Valuation Revision Books, taken annually from 1864 until the 1930s, are a great place to learn about your ancestor’s property.

In addition, the family pamphlet series has guides to everything from starting your research to using 17th-century census substitutes.

Another useful tool, the PRONI Historical Maps viewer, allows you to layer the modern Ordnance Survey Map of Northern Ireland (OSNI) with one of several historical OSNI maps, the earliest of which was made between 1832 and 1846.

3. Ulster Historical Foundation

The Ulster Historical Foundation was part of PRONI from 1956 until 1987, when the Foundation became a separate organization. Today, the Foundation provides collections that have one of three access levels: pay per view, free to view, and available to members only.

Among the free offerings are “Members’ Research Interests” and “Graveyards in Ulster,” while pay-per-view documents include vital records for counties Antrim and Down. Several collections are for members only, including an agricultural census of Down from 1803 and “Inhabitants & Householders in Downpatrick in 1790.”

Also worth exploring (and free) is the Getting Started section of the website. The first page includes a primer on Irish genealogy research. Sub-pages cover additional topics (such as civil parish maps), and one has video tutorials for using the website.

4. PlacenamesNI.org

At PlacenamesNI.org, you can browse for Northern Irish counties, baronies and parishes—though you’ll have to keyword-search for townlands. (Confused about each of those terms? Check out the pages that explain historical land units in Ireland.)

This is a good site to use if you have a partial or muddled place name, or if you’re not sure whether the place name you have is a parish or a townland. Each page for a place name includes a variety of information: the name’s Irish origin, background and historical name forms, plus a historical reference for them in each of these forms. Other articles explain how the Irish language is structured in place names.

PlacenamesNI.org is linked to the Placenames Database of Ireland (see No. 5 below). Despite links with this Republic of Ireland site, PlacenamesNI.org focuses on the six counties of Northern Ireland (and not the nine counties that make up Ulster).

5. Placenames Database of Ireland

The Placenames Database of Ireland includes information on more than 60,000 townlands in the whole of Ireland. The pages for each townland generally include basic information about the name, where it is on the “Irish Grid,” a link to archival records, a list of famous people born there, the name of the corresponding parish and (if relevant) a link to PlacenamesNI.org.

In addition, the Resources section has a great many historical maps, the earliest of which date to the 1500s. And the Glossary includes an overview of words commonly found in Irish place names, then plots them on a map.

6. Ask About Ireland: Griffith’s Valuation

Ask About Ireland is a great place to access Griffith’s Valuation and Ordnance Survey Name books. You can search Griffith’s Valuation, made to assess property values in the mid-19th century, by name or browse it by place.

Use Griffith’s in conjunction with the Valuation Revision Books at PRONI (see No. 2 above) to track your ancestor’s property up to the 1930s. Each result for Griffith’s Valuation is linked to a contemporary Ordnance Survey map.

The Ordnance Survey Name Books are interesting sources in and of themselves. They include notes and correspondence that mapmakers gathered about place names across Ireland. (Their task was to determine which names to include on the OS maps.) At time of writing, Name Books for some counties have not been digitized, since the project is a work in progress.

7. The National Archives of Ireland: Genealogy

The Genealogy page from the National Archives of Ireland has a variety of records that you can view online. These include the 1901 and 1911 censuses, surviving censuses and census substitutes from 1821 to 1851, tithe applotment books (1823–1837) and two collections of wills that collectively date from 1850 until 1922. Search results include index information and usually a link to the original image.

Other websites

- Belfast Newsletter newspaper index, 1737–1800

- Cyndi’s List: Ireland

- Eneclann

- Findmypast

- Genealogical Society of Ireland

- Historical Manuscripts Commission

- Ireland Old News

- Irish Genealogy Toolkit

- North of Ireland Family History Society

- RootsIreland

- ScotlandsPeople

- Ulster Ancestry

A version of this article originally appeared in the July/August 2020 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated February 2025.

Scots-Irish Books

By James M. Beidler

- The Book of Ulster Surnames by Robert Bell (The Blackstaff Press)

- The Family Tree Guide to Irish Genealogy by Claire Santry (Family Tree Books)

- Researching Scots-Irish Ancestors: The Essential Genealogical Guide to Early Modern Ulster, 1600–1800, 2nd edition by William J. Roulston (Ulster Historical Foundation)

- The Surnames of Ireland by Edward MacLysaght (Irish Academic Press)

- Surnames of Scotland: Their Origin, Meaning and History, reprint edition by George F. Black (Churchill & Dunn)

- Tracing Your Irish Ancestors, 5th edition, by John Grenham (Genealogical Publishing Co.)

- Tracing Your Irish Family History by Anthony Adolph (Firefly Books)

- Tracing Your Northern Irish Ancestors: A Guide for Family Historians by Ian Maxwell (Pen and Sword Books)

Scots-Irish Organizations

By James M. Beidler

- General Register Office of Ireland

- General Register Office Northern Ireland

- Linen Hall Library

- Mellon Centre for Migration Studies

- The Methodist Church in Ireland

- National Archives of Ireland

- National Library of Ireland

- National Records of Scotland

- Public Record Office of Northern Ireland

- Ulster Historical Foundation

A version of this article appeared in the December 2010 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated February 2025.

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com and affiliated websites.