Stephanie Logan Falls spent years researching her married surname, Falls. Despite her best efforts, she repeatedly ran into a brick wall in 1830s Tennessee. All record trails went cold. Hoping to find a connection to other Fallses, she ordered a genetic genealogy test for her husband’s father.

When she got the results, Falls was surprised to learn the DNA didn’t match any other Falls in the company’s database. Instead, it was a perfect match with several members of the Allen/Allan Surname Project. This triggered a relative’s memory: The family’s surname had indeed once been Allen. “Delia Falls didn’t marry Mr. Allen,” Falls says. “So the DNA is Allen, but the named stayed Falls.”

Her next step, of course, was to join the project. Armed with information from her newly discovered relatives, she broke through the stubborn brick wall and is now researching the Allen family in Tennessee and Ireland.

Is a DNA surname project right for you?

Can a DNA surname project like the Allen/Allan clan’s put similar success within your genealogical grasp? We’ll show you how participating in one can help you achieve your research goals—but first, it helps to understand the basics behind what a surname study does.

With the exciting technology of DNA testing, genealogists can make research strides by examining their surnames in greater detail than ever before. Surname projects are collaborative efforts using the results of DNA tests to study the origins of a surname and how people throughout the world with the surname are related.

Thousands of these projects exist, some with hundreds of members. One or two administrators typically run a surname project, organizing results, sharing information and recruiting new members to be tested, usually with the same testing company.

Take advantage of DNA kit sales and discounts.

At some companies, surname project participants can get a 10 percent or higher discount on a Y-DNA testing kit. This can represent substantial savings if you’re thinking about trying out a research theory by purchasing tests for family members or others with a certain surname. Be sure to ask your testing company about surname project discounts before you order your test.

The Science Behind Surname Studies

A simple fact of biology makes surname projects possible: The Y chromosome, or Y-DNA, a long piece of DNA found only in males, is passed down virtually unchanged from father to son. Conveniently, surnames are generally passed down the same way.

A male, therefore, should have the same Y chromosome—and the same surname—as his father, grandfather, great-grandfather, and so on. That means two males with the same surname and the same or similar Y chromosomes are often related through their paternal line.

Occasionally, the Y-DNA will accumulate a harmless mutation before it’s passed down to a son. Because these rare changes to the Y-DNA occur at a known rate, they act as a “clock” that can roughly measure time. When Y-DNA testing reveals that two males are related through their paternal line, genetic genealogists can use this “clock”—in the form of any differences between their Y-DNA results—to estimate the amount of time since their most recent common [paternal] ancestor (MRCA) walked the earth. By using the scientific information with genealogical records, the men may be able to determine who that MRCA was and how their family branches diverged.

Here are six ways surname studies can help you find answers to your genealogical quandaries:

1. Test relationships among similar surnames.

You have a sneaking suspicion that your Causley family is related to the Causeys across town, and maybe even the Clauses two states over. When you can’t find the records to prove it, a surname stufy may help. Participants in projects covering surname variations often hope to find out whether those names trace back to a single individual. Their Y-DNA results, analyzed as a whole, let scientists answer these questions.

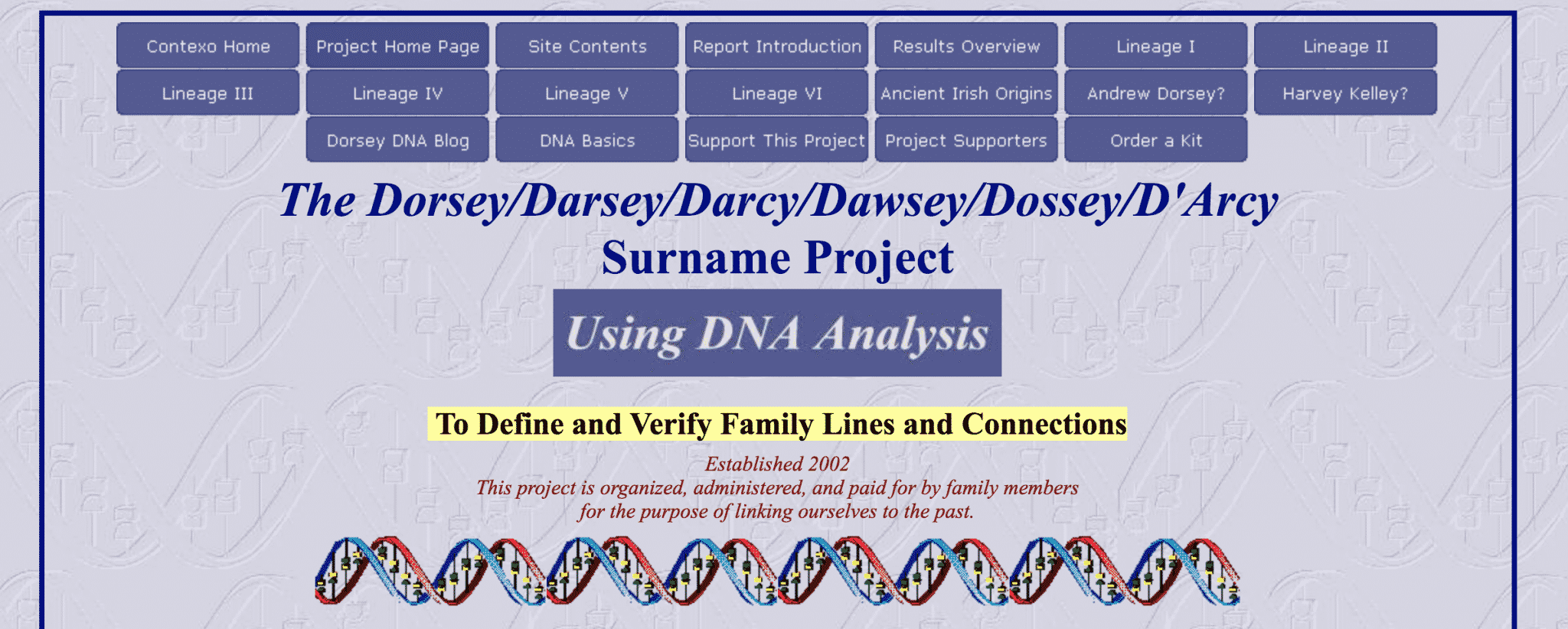

For example, the Dorsey/Darsey/Darcy/Dawsey/Dossey/D’Arcy DNA Project lists more than 15 surname variants of Dorsey. The project has used genetic genealogy to prove the study participants are descended from several different male lines—so not all the surname variants are related within the relatively recent past (at least 400 to 500 years). Indeed, as the results page of the Dorsey DNA Project suggest, participants fall into more than 10 different lineages.

As a surname project accumulates members, the Y-DNA results often begin to cluster into groups of closely related individuals. Sometimes they cluster into one group of almost everyone with the surname. More often, though, the results group into two, three or more different clusters, each containing individuals who are closely related within the cluster but more distantly related to the males in the other clusters.

This clustering allows genealogists to determine whether people with those surname variants are related. If the results for surname variant A1 aren’t similar to the results for surname variant A2, then it’s less likely the members named A1 and A2 descend from the same person in the recent past. There’s probably another explanation for the surname similarity.

On the other hand, if surname variants A1 and A2 have similar results, they probably have a common surname source, and the variance has a simple explanation, such as a misspelling. Using the Y-DNA “clock,” genetic genealogists can estimate how many generations lived between the surname split and the modern-day males who were tested.

2. Connect with genetic cousins.

Finding Y-DNA cousins not only will make family reunions more robust—it also could lead to information about your common family line.

Imagine an ancestral chart following the male line of every person on earth for the last 100,000 years: Scientists have discovered the lines would trace back to one man, sometimes called Y-chromosomal Adam (no affiliation with the Biblical Adam), who lived in Africa between 60,000 and 100,000 years ago. Every male has a copy of Y-chromosomal Adam’s Y-DNA, although it’s mutated considerably in the intervening 100,000 years.

Depending on how much that Y-DNA has changed and how closely it matches other individuals’ DNA, genetic genealogists can determine the paternal relatedness of two males. Surname projects can take advantage of that ability and connect you with other members who might be closely or even distantly related.

Share the research workload!

By collaborating on research tasks, genetic cousins can save time and money, avoiding duplicating tasks. For many, connecting with cousins around the world further defines a sense of self.

These connections can be especially important to adoptees. Many states restrict vital records and other official documents that reveal birth parents’ names, but identifying genetic cousins can help an adoptee learn his biological surname. By joining the appropriate surname project, he may be able to narrow the surname to a particular branch or ancestor. Several adoptees have already successfully identified biological fathers using Y-DNA testing.

3. Break through brick walls.

Ever since that first caveman genealogist tried to trace his family tree, brick walls have troubled family historians. Due to missing or nonexistent paper records, confusing oral tradition and non-paternal events such as adoption or infidelity, genealogists often get to the point where traditional paper research is unable to identify an individual’s origin or parents.

Surname projects offer the opportunity to break through brick walls in the paternal line. For example, if all your research efforts end with Richard Adams of Boston in 1713, you can have his male-line descendant join an Adams DNA surname project to find out if that Y-DNA matches a descendant of another Adams in or near Boston at the time.

Although a match won’t specify how the men are related or tell you the name of Richard Adams’ father, it might provide clues or keep you from researching down the wrong path.

Help narrate your ancestry.

If you’ve discovered a non-paternal event caused by unrecorded adoption or infidelity, a surname project can help you determine the biological surname of the ancestor who represents the break in the Y-chromosomal line. Again, this won’t immediately reveal the biological father’s name, but breaking through this roadblock allows the genealogist to point his or her research in a more productive direction.

At the very least, a Y-DNA test will give you a peek around a brick wall. By revealing that your Y-DNA belongs to a traditionally European haplogroup, for example, the test results tell you that your ancient paternal ancestry was most likely European. An unexpected African haplogroup might uncover a hidden paternal story. The “peek” usually won’t give you names, dates or other statistics, but it might help narrate the lost story of your ancestry—one that wasn’t recoverable through traditional research.

4. Prove or disprove a theory.

Philip Bettinger, who fought in the Revolutionary War and settled the central New York frontier, today has thousands of descendants across the United States. But a number of other US Bettinger families have no known link to him. Given the rarity of this surname, many of Philip’s descendants have wondered if the families are related through someone who lived in Europe, before the clans emigrated. To find out, I established the Bettinger DNA Project in 2006.

In 2009, a Bettinger whose paper trail didn’t lead to Philip joined the project and took a Y-DNA test. Where historical records had failed, the test results showed that all Bettinger families in the United States aren’t related in recent history. Not only that, but they belonged to different haplogroups, suggesting that at least 45,000 years had passed since the MRCA in their male line. The surname project, therefore, disproved the theory that all Bettinger males were paternally related.

Find common historical ties.

You can analyze a wide variety of genealogical theories through surname projects. Members of the Lost Colony of Roanoke Y-DNA Project, for example, hope to learn whether the Roanoke, NC, colonists, who mysteriously disappeared in the late 16th century, perished or were assimilated into local native populations. Eligible men have a surname of interest (more than 150 are included) and heritage from American Indian populations, eastern North Carolina and/or England. By comparing their Y-DNA results to those from known male relatives of the colonists, project administrators could solve an ancient mystery.

5. Uncover a place of origin.

Many genealogists, particularly in the United States, encounter a brick wall when attempting to follow an ancestor back to his country of origin. Lost or destroyed records can hide the birthplace, and a vague or altered surname can preclude attempts to guess the correct country.

The clustering of Y-DNA results in a surname project can uncover clues, especially if your results indicate your Y-DNA is closely related to that of immigrants from a particular place. Surname projects also can help answer other origin-related questions—say, whether all same-surnamed families from a country are related, as in my Bettinger project, which suggested different Bettinger lines come from different countries.

6. Confirm traditional research.

Genetic genealogy works best when combined with tried-and-true traditional research in historical records. Participating in a surname project can help you confirm what you’ve learned from those resources.

Test results can verify, for example, that your Y-DNA indeed closely matches other descendants of Richard Adams in the Adams surname project. Alternatively, clustering in the surname project may tell you that you haven’t missed something in your research—the two families truly aren’t connected along their paternal lines.

That can be satisfying, but it’s also important to note that taking a Y-DNA test and joining a surname project could refute years of genealogical research. For many of us, our DNA is the last witness to numerous mysteries and secrets that have otherwise been successfully hidden for generations. Nonpaternity events, unrecorded name changes and other breaks in the Y-chromosomal line can cause paper records and DNA results to reveal different ancestral stories. Be prepared for this possibility before joining a surname project.

Of course, there are no guarantees: A surname project may not be able to answer every question you have. But such studies have helped thousands of genealogists like Falls make research progress. You just might benefit, too.

Study Groups

The first step to joining a surname project is, of course, finding one covering the name you’re researching. Each of the following websites has an index of projects for thousands of surnames. Also try a Google search on your last name and DNA surname study.

If you can’t find a project, don’t be afraid to start one. Coordinating a surname project can be a rewarding experience and a genealogical lifeline to other researchers.

A version of this article appeared in the September 2010 issue of Family Tree Magazine.