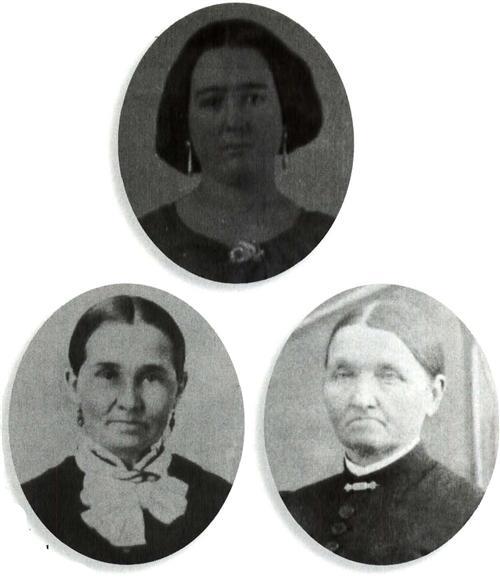

Does the mystery ambrotype (top) show the same woman as these photos from the 1880s (above left) and early 1890s (above right)?

Have you ever laid out all the old photos you own of a single individual? If you have several identified photographs of an ancestor at various ages, you can create a picture timeline illustrating that person’s life story. Such a timeline might even help you identify some of the mystery pictures in your collection.

For example, Family Tree Magazine reader Audrey Staples knows she owns at least two photographs of her great-grandmother Anna Sofia Johannesdotter Sandberg Peterson. She was born Feb. 2, 1829, in Jonkoping, Sweden, and died about 1895.

Staples thinks she might also have an image of her great-grandmother as a young woman. It’s an ambrotype in an embossed leather case with a hook-and-eye clasp. Ambrotypes first appeared in 1854. They’re actually negative images on glass but appear as positives because they’re backed with a dark material or varnish. The image also appears flipped, like looking in a mirror — in Staples’ photo, the wedding ring appears on the “wrong” hand.

One of the distinguishing features of an ambrotype is that you can see through the image as the backing deteriorates and flakes away from the glass. (Staples’ ambrotype shows no visible damage or deterioration, however — it’s in beautiful condition.) An ambrotype usually consists of a case, the image, a mat that frames the picture, a piece of cover glass and a thin piece of edging, called a preserver, that keeps the image in the case.

Since ambrotypes date from 1854, this young woman had her picture taken after that — but when? Anna Peterson was married May 4, 1855, in Jonkoping, and this woman is wearing a ring on the appropriate finger. This could be a wedding photograph, but only clothing details can help determine if it was taken around the right time. She is wearing a dress with a fan-shaped bodice gathered around the waist, with sleeves featuring a tight upper arm that flares out above the elbow and braid trim around the lower edge of the sleeve. She is not wearing a collar; instead she has a simple brooch. Her hair is looped over her ears and she’s wearing drop earrings. Her sleeves suggest a date in the 1850s, although she is not wearing the lace collar and cuffs usually associated with this dress style. While contemporary weddings usually featured white dresses, many 19th-century brides selected colored fabrics and simple dresses instead of the Victorian ideal.

If this is a wedding picture, Staples owns three photographs of her great-grandmother that all appear to be taken around significant points in her life. First, the ambrotype seems to be a formal wedding portrait. The second photograph of a middle-aged Peterson dates from the 1880s — you can tell because of the style of her dress bodice and the scarf around her neck. The timing of this image is significant: She immigrated to the United States in 1883, though it’s unknown whether this photograph was taken in Sweden or America. The third photograph dates from the late 1880s to early 1890s, based on the style of the neckline of her dress. Perhaps it was taken just prior to her death in 1895. In looking at these three images, you can create a chronology of her life and watch her age. Each portrait reveals additional facial lines and some weight. Peterson’s bright personality shines through in the first two pictures, while in the third portrait she appears ill.

Try putting all your family photographs in chronological order to see what you can learn about your unidentified pictures. Look for clues in facial features such as the eyes and the shape of the nose, ears and face. You might be surprised to discover several portraits taken at different life stages, much as Staples did.

Think about the photographic patterns in your family. Some individuals had their pictures taken only occasionally; others went on a regular basis. So an ancestor who regularly posed for portraits isn’t likely to miss an opportunity to photograph the birth of a child or a wedding. If you’re missing photographs of those events, ask about the collections of other family members. Apparently, Anna Peterson posed for a photographer only at transitional phases of her life, but that doesn’t mean the same is true for your relatives.