Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

It’s no secret that tracing African American roots can be a challenge. Before the Civil War, the enslaved were excluded from many public records and mentioned only vaguely in others; enforced illiteracy kept many people from writing their stories; and the forward flow of family memory was disrupted when children were sold away from parents. After the Civil War, some memories were just too painful to pass along.

In addition, record-keeping issues persisted: African Americans were often segregated in records as blatantly as they were on buses and in theaters. Those segregated records aren’t always as easy to access as mainstream ones.

The seven African American sources listed here can help you strengthen your family tree at its trunk—where it needs the most support. Along the way, you’ll learn about recurring family names, hometowns, white associates and more. These clues—and the experience you gain as a researcher—will help you recognize pre-Civil War ancestors in the more complicated records of pre-Emancipation days.

ADVERTISEMENT

1. Family memory

“Family memory is always your most important source,” says Tony Burroughs, professional genealogist and author of Black Roots: A Beginner’s Guide to Tracing the African American Family Tree (Fireside). “If you don’t go to your family first and often, you will have problems all the way down the road.”

Family memory is “both an oral source and a physical source,” says Burroughs. “Things in your family’s head—stories, information, connections, names, places”—can provide background, but physical items in relatives’ homes, such as boxes and files, may hold funeral programs, newspaper obituaries, letters and other memorabilia offering additional clues. For example, “funeral programs have obituaries inside and are very big in the African American community, and many people save them,” Burroughs says. Black Roots features chapters on how to get the most from both family memories and memorabilia. Also, be sure to connect with multiple family members, as memories may be spread thin across many relatives you don’t even know.

2. Federal censuses

“The federal census is the mother lode,” says Henry Louis Gates Jr., host of PBS series including “Finding Your Roots With Henry Louis Gates Jr.”

ADVERTISEMENT

“We’ve rarely had difficulty finding an African American in the census [beginning in 1870].”

Federal censuses are searchable for most or all years on websites including HeritageQuest Online (available at libraries), Ancestry.com, Archives, and FamilySearch.org.

“Analyzing each census is critical,” says African American genealogy expert Deborah A. Abbott. “Read each entry all the way across. Compare each census to the next one.”

It’s typical for details to change from census to census, she adds. “People will appear and disappear, ages will fluctuate, probably race is going to fluctuate, too.” You may find the same person recorded as white, mulatto or black.

“I make sure the people I’m looking for are in place—the names and children are right,” Abbott says. “I look for migration patterns in the neighborhood, like if they all come from the same place. I watch for other families of the same surname who may be related, or with white families, may have had a slaveholding relationship.”

“People will appear and disappear, ages will fluctuate, probably race is going to fluctuate, too.”

Deborah A. Abbott

Former slaves would sometimes—but not always—use the surname of the most recent slaveholder. Abbott advises recording every known name of a relative; he or she may appear under first, middle or nicknames.

When you’re ready to look for ancestors from pre-Civil War days, you may find yourself using federal censuses in different ways. Enslaved ancestors are described in the 1850 and 1860 slave schedules by gender and age under slave owner name. You may also find yourself tracking the migrations of slaveholding families; however, don’t assume that your black ancestors were enslaved at the time of the Civil War—about 10 percent were not.

3. Vital records

“Vital records help you connect families generations back,” says Abbott. “They name parents and death dates and the like. But they generally weren’t kept until the late 1800s or early 1900s, and all the states have different rules.”

Furthermore, she says, “You may have to look in several places. Vital records pertaining to blacks may be segregated, or they may be intermingled with everyone else’s.” Marriage and birth records may have been filed at the time of the event or much later.

Before Emancipation, free blacks are listed in any existing vital records, says Abbott. Births of slaves were sometimes recorded at the county courthouse (with records pertaining to property) or in the slaveholder’s personal papers. Slave marriages were illegal, so they weren’t recorded, but you may come across other records that describe family relationships.

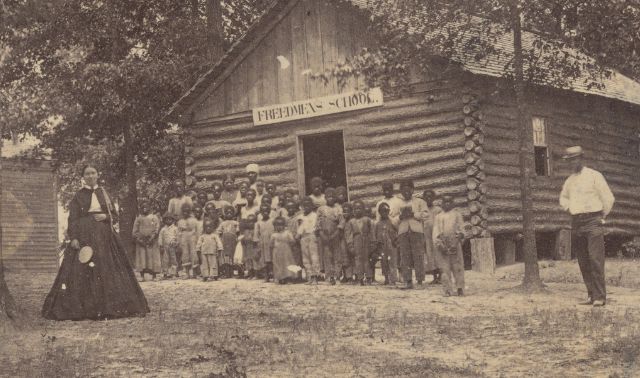

Immediately after Emancipation, many states and the federal Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands—commonly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau—allowed formerly enslaved couples to file marriage declarations to legalize their relationships. These declarations may be recorded separately from other marriage records. “Colored marriages” were generally recorded in segregated record books well into the 1900s.

To get past these record-keeping obstacles, Abbott asks a lot of questions at courthouses and archives, and she leaves herself plenty of time to explore little-used or unindexed resources. Burroughs says he looks for county vital records inventories created by the Historical Records Survey during the Works Progress Administration era of the 1930s and 1940s. These inventories will mention segregated and delayed records. To find them, keyword-search the phrases “historical record survey” or “inventory county archives” plus the name of the state, county or city in the FamilySearch catalog, WorldCat and regional or local libraries. Check to see if titles have been digitized on Google Books or Internet Archive.

4. African American newspapers

Tim Pinnick, author of Finding and Using African American Newspapers (Gregath), says, “In my belief, African American newspapers hold the key to genealogical research success. He adds, “They represent one of the few sources where the daily activities of black communities are documented. These communities are full of former slaves, US Colored Troops soldiers and scores of ordinary folks who did extraordinary things. But they got captured in the black newspapers, not the mainstream newspapers.”

Black newspapers published details about births, deaths, marriages, military service, church affiliation, employment, migration and former slavery status. Also included were photos, social column comments and African American viewpoints that would not have been represented in the mainstream press.

In my belief, African American newspapers hold the key to genealogical research success.

Tim Pinnick

Burroughs likes to look for black ancestors in the Chicago Defender (indexed at ProQuest Historical Newspapers, a service available at many libraries). “The Chicago Defender is a national newspaper with columnists and reports from all over the United States,” says Burroughs. “The more names they mentioned, the more papers they could sell. There’s lots of local gossip.”

The Library of Congress’ Chronicling America website is Pinnick’s go-to source for finding African American newspapers. You can also search for digitized issues or indexes in historical newspaper databases and on library and society websites.

5. Freedmen’s Bureau records

The Freedmen’s Bureau captured information on newly freed African Americans after the Civil War. This federal government agency provided relief and support to the former slaves and newly impoverished whites whose way of living was so profoundly altered by the end of slavery.

“Freedmen’s Bureau records may hold marriage declarations, school records, the names of a person’s former owner and more,” says Abbott. Labor contracts, relief records, descriptions of racial violence and transportation requests are also among records created by state field offices. Records are indexed by state and county, but not by name, Abbott explains. You have to search within separate record groups created at the each level.

Consult a full description of surviving records here. Look for a growing number of indexes at The Freedmen’s Bureau Online. You can also search over 3.5 million Freedmen’s Bureau records on Ancestry.com for free. Learn more about Freedmen’s Bureau records and Freedman’s Saving and Trust Co. records (see below) in A Genealogist’s Guide to Discovering Your African-American Ancestors by Franklin Carter Smith and Emily Anne Croom (Genealogical Publishing Co.).

6. Freedman’s Saving and Trust Co. bank records

The Freedman’s Saving and Trust Co., also known as the Freedman’s Savings Bank, is “also a great resource,” says Kenyatta D. Berry, author of The Family Tree Toolkit and co-host of the “Genealogy Roadshow” on PBS.

The Freedman’s Saving and Trust was a federal bank for freed slaves and their families from 1865 to 1874. Nearly a half million clients and their relatives appear on registers of depositors’ signatures, which requested a client’s name, birthplace, childhood home, residence, age, occupation and employer; names of spouse and children; and names of parents and siblings. Many cards don’t note all the requested information, but some contain additional items such as the name of a former slave owner or plantation, and comments on whether relatives were still living.

“I haven’t located records for my family; however, it’s a wonderful resource when I’m doing research for others,” Berry says. It’s often the first place she turns to after locating individuals on censuses in 1870 and, if they were free, 1860.

Bank records are available at the National Archives as well as on FamilySearch. Berry encourages researchers to search them even if their ancestor didn’t live in a branch city. “While not every African American banked with the Freedman’s Bank, maybe their family members did. Perhaps a brother lived near a Freedman’s Bank branch, and he opened an account. He may have provided pertinent information on the family.”

7. History books and compiled biographies

History books and compiled biographies are top-notch resources. “Sometimes you have to stop looking for the ancestor’s name and read the history of the area to figure out what was going on,” Abbott says.

Search for local histories through the Library of Congress’ online catalog (follow the search format Cook co for a county and Chicago (Ill.) for a city). Look on WorldCat for books available through interlibrary loan. You can find many out-of-print editions at Google Books, Internet Archive and FamilySearch.org (click on Books).

Gates recommends reading black history, too, not just local history. He’s the author of Life Upon These Shores: Looking at African American History, 1513–2008 (Knopf). He also recommends From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African Americans by John Hope Franklin and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham (McGraw-Hill) and Children of Fire: A History of African Americans by Thomas C. Holt (Hill and Wang). Also check your local PBS station for his six-part documentary series, “The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross.”

Compiled biographies may lead more directly to your ancestors. “The African American Biographical Database indexes more than 40,000 entries from nearly 300 black biographical dictionaries, mostly published before 1930,” Berry says. “Mostly you’ll find doctors, lawyers, teachers and other community leaders.” She also likes History of the American Negro and His Institutions by Arthur Bunyan Caldwell (available on Google Books). “This is one of my favorite underutilized resources. He interviewed prominent people throughout the South and gathered valuable genealogical information.”

A version of this article appeared in the March/April 2013 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in affiliate programs through Amazon and Genealogical Publishing Co. It provides a means for this site to earn advertising fees, by advertising and linking to affiliated websites.

ADVERTISEMENT