Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Each day brings a new story of a successful family reunion brought about by DNA. Adoptees find their birth families, donor-conceived children call up their biological fathers, and genealogists break down brick walls to uncover their ancestral origins.

But other stories caution you against taking the test, claiming your privacy is at risk or casting doubt on the test’s accuracy. But with information about the three kinds of DNA tests (mtDNA, Y-DNA and autosomal DNA) flowing freely from a myriad of sources, not every news reporter has all the facts.

It’s time to set the record straight. We’ll examine six pervasive myths about DNA tests and what they can or can’t do, allowing you to set realistic expectations.

ADVERTISEMENT

1. You only need one kind of DNA test.

Status: Plausible

Autosomal DNA

We most often hear about autosomal DNA (atDNA), as it is the kind that reveals our biogeographical origins (ethnicities) and connects us to living cousins. You get half your atDNA from your mother and half from your father. Thus, it can help you with genealogy questions on both sides of your family. However, because of the way it is inherited, autosomal DNA can only help you back about six generations.

Y-DNA

DNA on the Y chromosome (also called Y-DNA) is passed virtually unchanged from father to son. So a great-grandfather should have the same Y-DNA as his son, his son’s son and so on. You can use Y-DNA to trace your direct paternal lineage, which is represented by the top line of a pedigree chart. Y-DNA testing can help you sort out individuals with the same or similar surname into family groups, or help you find a surname for a foundling or adoptee. Better still: Y-DNA can help you answer family history questions back at least 10 generations!

Because women don’t have Y chromosomes, a female researcher who wants to trace her direct paternal line will need to turn to someone with the same Y-DNA as her biological father. She could ask her father, brother, paternal uncle, a male cousin (her father’s brother’s son) or a nephew (her brother’s son) to take a Y-DNA test.

ADVERTISEMENT

mtDNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is used to trace a direct maternal line. Mothers pass their mtDNA to all of their children, but only daughters pass mtDNA on to the next generation. Genealogists can use mtDNA in much the same way as Y-DNA. mtDNA mutates more slowly than Y-DNA does, making it even harder to predict when you should look for your connecting ancestor. But like Y-DNA, it can give you information about your ancestors up to 10 generations in the past.

Typically, genealogists use mtDNA to explore their ancient ancestry or to weed out people who aren’t related through their maternal lines, rather than those who are. You might be able to document a relationship between two exact mtDNA matches, but two people with one or more differences in their mtDNA usually can’t determine their shared ancestor in a genealogical useful time frame.

2. You can get DNA from stamps or hair samples.

Status: Confirmed

We can confirm this myth with a caveat: Yes, but we can’t quite use it yet. Just a couple of years ago, this myth had a hard no. While you can find DNA on licked stamps and envelopes, used razors, and in the root of uncut hair, it can be tricky to extract for genealogical purposes. This category of samples (called “special samples”) defy the process historically used by genetic genealogy companies.

But the science continues to evolve, and some services now offer special sample testing. While expensive, the tests allow for a direct comparison of the DNA from a postage stamp to that of a living person. Test takers can then use this information to determine genetic relationships, such as between parents and their children.

Despite these scientific advancements, the big genetic genealogy companies don’t currently offer testing using special samples. Nor do they compare that kind of data with their databases to find genetic matches. However, in one special case, Living DNA used DNA collected from a postage stamp to help a woman found as a baby in a blackberry bush to locate her family. And the company has indicated it’s interested in eventually offering these services.

Though not one of the well-known companies, Australia-based To The Letter DNA now offers DNA extraction from your stamps and letters. However, no company can truly guarantee a usable DNA profile, and the service is expensive: Customers pay more than $200 to even find out if they have a workable sample. If the sample is viable, customers will have to pay hundreds of dollars more to have it analyzed.

3. DNA tests can pinpoint locations where your ancestors lived.

Status: Busted

Locating your ancestors’ tribe or location is the holy grail of genetic genealogy. Unfortunately, much like the grail itself, it is quite elusive. Even just the word ethnicity is enough to get some geneticists’ dander up, as there are conflicting opinions about what that word even means. As a result, a handful of factors stand in the way of ethnicity estimates being able to reveal where your ancestors lived in detail. Scientists can make inferences about your ancestry based on trends among populations, but they currently can’t say for sure that your ancestors lived in a specific country, much less a specific town.

The importance of movement

Some of the categories defined by DNA companies are purely geographical, like Northern Europe or the British Isles. Others are cultural, like Jewish or Inuit. As Shannon Combs-Bennett points out in her webinar, “What’s Up With My Ethnicity Estimates?”, ethnicity reports are based on a modern interpretation of ethnicity and culture.

If your ancestors and their offspring had stayed in one geographic region and never allowed outsiders to enter, we could easily distinguish their DNA (and yours) from the DNA of people living in other regions. Over time, all of the inhabitants of your region would come to share specific genetic mutations (usually harmless changes in DNA). This would identify them as a distinct population, in much the same way as a surname identifies members of a family.

But our ancestors didn’t stay in one place. For thousands of years, humans have moved about, leaving their genetic imprints wherever they procreated. This makes it increasingly difficult for geneticists to distinguish one region’s population from another’s.

Understanding reference populations

Testing companies analyze a person’s genetic makeup by comparing his or her DNA to a reference population of DNA samples from modern individuals living in various regions. This is key to understanding ethnicity estimates: We are using modern-day populations to help us make predictions about where our ancient ancestors lived.

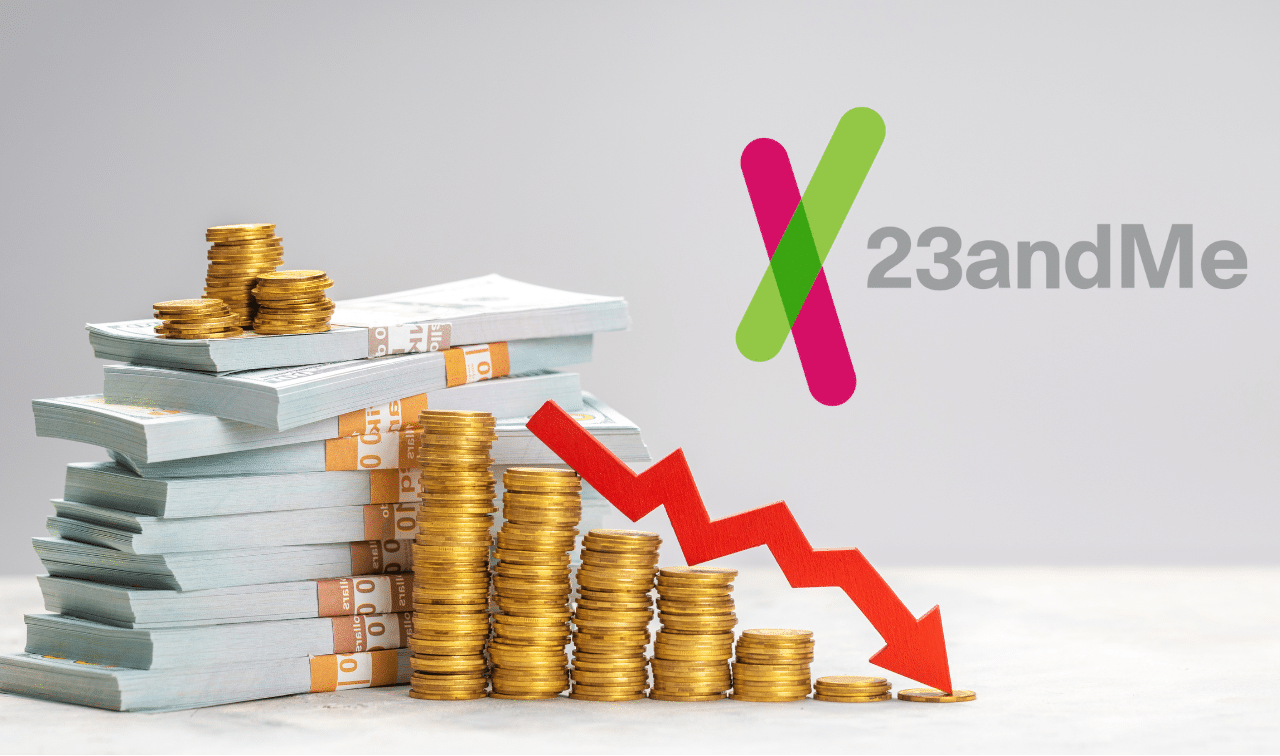

The “Big 5” companies (23andMe, AncestryDNA, FamilyTreeDNA, Living DNA and MyHeritage DNA) are doing their best to use statistical data in conjunction with historical information about populations and migrations to give us these estimates. But in the end, they are just estimates—best guesses as to where you might find your ancestors thousands of years ago.

Of the Big 5, LivingDNA comes the closest to pinpointing specific geographic regions for those with ancestry in the British Isles. They break down the United Kingdom into more than 40 geographic subregions, making it the only to provide that level of distinction. (Though, of course, this analysis is limited to those with English, Scottish, Welsh or Irish ancestry.)

In a somewhat similar vein, AncestryDNA offers an interesting view of your origins with its Migrations tool. Migration groups show you where your ancestors were, not thousands of years ago, but between the years 1750 and 1900. By defining this timeline, they are often able to better deliver origins results that match up with what you already know about your family history.

Apply ethnicity estimates

The best way to use your ethnicity estimates is to combine them with traditional genealogical research methods. As more people get tested and contribute both their DNA test results and their family trees to online databases, scientists will be able to identify additional patterns and draw more accurate conclusions.

4. The results of ancestral DNA tests are 99.9% accurate.

Status: Plausible

In the previous section, we discussed how biogeographical results are just estimates, so they aren’t meant to be precise. The methodology isn’t an exact science, and testing atDNA (which is inherited from both mothers and fathers) muddies the waters when trying to uncover family information. With that in mind, your ethnicity results are not 99.9% accurate, nor can the testing companies provide you that high level of confidence.

However, atDNA test takers also receive a list of DNA cousins, and these results are generally more reliable. Cousin-matching also isn’t an exact science, but (with careful analysis) you can learn valuable information about your family.

atDNA test results can accurately determine close genetic relationships. In general, cousin-matching can identify relationships between close family members (parents/children, siblings, half-siblings, aunts and uncles) with a high degree of accuracy.

But, for other relationships and tests, you’ll need to analyze your results before drawing any solid conclusions. You’ll need additional sources of information to correctly determine these more-distant relationships. Paper records can help you determine how you and your “1st–3rd cousin” match relate to each other, for example.

mtDNA and Y-DNA matches are a different story. For one thing, these tests don’t provide estimates for how you and your matches relate, as Y-DNA and mtDNA cannot specifically define relationships. Y-DNA matches could be brothers, or they could be sixth cousins. mtDNA matches are even worse; they could be sisters, or 20th cousins.

Instead, you’ll have to analyze how many markers you and your mtDNA or Y-DNA share. The more markers you share (or, conversely, the fewer mutations you have from each other), the closer you’re related.

For example, men can choose from Y-DNA tests that examine between 12 and 111 markers (or locations) on the Y chromosome. The more markers tested, the more accurately the test can establish how closely related the participants are. If two men have the same surname and the same Y-DNA test results (or results with only one or two differences), there’s a good chance they’re related within a genealogically significant time period.

Conversely, mtDNA changes relatively slowly, you’ll often find exact matches with whom you do not actually share recent common ancestry. In that sense, mtDNA is not very accurate at telling you if you do or don’t share common ancestry with someone else.

5. DNA can tell you how you’re related to someone else.

Status: Plausible

DNA tests can be great tools in helping you find your living relatives. However, you’ll need to supplement your results with good ol’ fashioned genealogy research.

An atDNA test can help you identify genetic relatives, but it can’t tell you exactly how you are related to someone else. Your results will provide a relationship estimate (e.g., “3rd cousins”), some of which are vague (e.g., “3rd–5th cousins”). You’ll have to figure out the details yourself.

This is no small feat. For example, you and a third cousin should share a common set of great-great-grandparents. But you have eight sets of those! You’ll need to do heavy genealogical legwork to determine which set connects you and your newly found relative.

You could also use Y-DNA to help you in your search. However, even a perfect Y-DNA match can’t prove whether you’re related through your great-great-grandfather or a more distant ancestor. You’ll need to find records to test your hypothesis.

Likewise, you could employ mtDNA in certain cases, but you would have to significantly target your search. For example, if you’ve documented that Janice is a direct maternal descendant of a great-great-grandparent couple who is also your direct maternal ancestors, then you could compare Janice’s mtDNA to your own. If you match, there is a good chance that you are on the right track. But if any of those caveats aren’t true (e.g., if any of that research is incorrect), mtDNA won’t be able to help you.

6. The government or insurance companies can use your DNA against you.

Status: Busted

Are you nervous that your DNA test results end up in an online database? You can take some comfort in knowing that testing companies take your privacy seriously, and they won’t integrate your results into their online matching databases without your consent. And if you do want to make your information available to genetic cousins, you can determine how much personal information you want to reveal. You don’t even have to use your real name.

Testing companies safeguard customers’ DNA specimens by attaching a bar code (not personal information) to each sample, making them difficult to trace back to you. In addition, you can choose to have your specimens destroyed.

Furthermore, health insurance companies are forbidden by law to use genetic information to deny coverage or charge higher premiums. Congress passed the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) in 2008, forbidding discrimination based on genetic predisposition to diseases. Even if insurance companies were to get your genetic information (which is highly unlikely, as each company’s database is private), they wouldn’t be able to use it for nefarious purposes.

You should also note that there are differences between each company’s private database and the more public online databases. In situations like the Golden State Killer case, law enforcement used the public database at GEDmatch to make their query, rather than requesting DNA information directly from a testing company. So before you consider uploading your results to third-party platforms like GEDmatch, make sure you understand how your results might be used.

Be aware that companies sometimes offer new features or update their terms. For example, Family Tree DNA earlier this year announced it would begin allowing law enforcement agencies to use its DNA data to solve certain cold cases.

Shortly after, the company updated its policy so users had to opt in to this feature, but the change is a reminder to regularly check your testing company’s terms of service to make sure nothing is appearing that shouldn’t. Read every form, and be sure you fully understand what a company can and cannot do with your DNA.

Share this slideshow with your genealogy group!

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the October/November 2019 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: February 2025

ADVERTISEMENT