Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Jump to:

1896 and 1921: The 1890 Census Fires

1897: The Ellis Island Fire

1973: National Personnel Records Center Fire

Courthouse Fires and Burned County Records

“I lost her in the 1890 census!” If you’ve ever had cause to say this, you’re not alone. Unfortunately, the 1890 census isn’t the only major US record set that’s gone up in smoke. Other conflagrations have burned gaping holes in the collective historical record. Most notably: military service records for more than 16 million Americans and passenger records for a half-century of arrivals to New York City. Entire courthouse collections have been consumed, too, including vital records, probate files, deeds, court cases and more.

Behind these disappointing, frustrating genealogical disasters are alert watchmen, brave first responders, bewildered immigrant detainees and government officials of varying competence. We can at least be glad that three of the major fires reported here involve no loss of life—just loss of history.

ADVERTISEMENT

But the proverbial smoke clouds produced by these record losses aren’t without silver linings for researchers. Not every loss was complete. And not every loss was final—some records have actually been recreated. Though the following fires ruined millions of documents, they don’t have to ruin your family history research.

1896 and 1921: The 1890 Census Fires

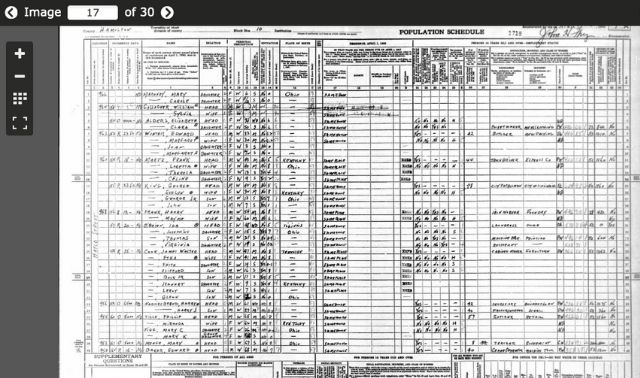

Thousands of family history researchers curse the loss of almost the entire 1890 US census. After learning of its destruction due to a fire nearly a century ago, genealogists quickly begin to “skip that year” in their record searches, turning instead to city directories, tax records and other substitutes that might name an ancestor during those key years between 1880 and 1900.

The missing 1890 census isn’t as simple as “it was lost in a fire.” Actually, different parts of the census burned in not one, but two fires. After the second and more devastating fire, the surviving waterlogged records were left neglected, then quietly destroyed years later by government administrators.

ADVERTISEMENT

The ill-fated 1890 census was taken at a critical time in US history. The population had topped 50 million in 1880 and climbed by another 25 percent in the following decade. Foreign-born residency jumped a third during those years. Inside the country, a restless population moved westward and into urban centers. The 1890 census captured a nation in motion.

It also collected individual information of unprecedented genealogical value. For the first time, each family got an entire census form to itself. Race was reported in more detail. Questions appeared about home and farm ownership, English-language proficiency, immigration and naturalization. Civil War veterans and their spouses were noted. Questions about a woman’s childbearing history first appeared. Additional schedules captured even more about people in special categories, such as paupers, criminals and the recently deceased.

The 1869 fire

By 1896, the Census Bureau had prepared statistical reports. Then a disaster occurred—one almost nobody remembers now because future events would overshadow it. A fire that March badly damaged many of the special schedules. It was a loss, but probably wasn’t considered tragic. After all, statistics had been gathered and the population schedules were still intact.

Over the next 25 years, many Americans lobbied for the construction of a secure facility for federal records. But there was still no National Archives. The 1890 census was stacked neatly on pine shelves just outside an archival vault in the basement of the Commerce Building in Washington, D.C.

The 1921 fire

Late in the afternoon of Jan. 19, 1921, Commerce Building watchmen reported smoke emerging from pipes. They traced the source to the basement. When the fire department arrived a half hour later, they first evacuated employees from the top floors. By that time, intensifying smoke blocked access to the basement. Thousands of bystanders watched fire crews punch holes in the concrete floors and pour streams of water into the basement. Firemen continued the deluge for 45 minutes after the fire had gone out. Then they opened the windows to diffuse the smoke and went home.

Anxious census officials had to wait several days for insurance inspectors to do their jobs before they could access the scene of the fire. Meanwhile, census books that hadn’t burned sat in sooty puddles on charred shelves. When officials finally tallied the damage, they found about a quarter of the volumes had burned. Another half were scorched, sodden and smoke-damaged, with ink running and pages sticking together.

The Census Bureau estimated it would take two to three years to copy and save the damaged records, but it never got the chance. The moldering books were moved to temporary storage. Eventually they came back to the census office, but the subject of restoring them didn’t come up again. Twelve years after the fire and without fanfare, the Chief Clerk of the Census Bureau recommended destroying the surviving volumes. Congress OKed this final move the day before the cornerstone was laid for the new National Archives building.

Of the nearly 63 million people enumerated on the 1890 census population schedule, only about 6,300 entries (0.0001 percent) survive. Worse yet, a backup protocol followed for previous censuses had just been dropped: The 1890 census was the first for which the government didn’t require copies to be filed in local government offices.

The surviving records

As sad as this story is, it could’ve been worse. Those concrete floors prevented the 1921 fire from spreading to the upper floors, which housed the 1790 to 1820 and 1850 to 1870 censuses. Inside the basement vault were the 1830, 1840, 1880, 1900 and 1910 censuses, but only about 10 percent of the records were damaged to the point of needing restoration. About half of the 1890 veterans schedule survived. The 1920 census was in another building entirely. So while the losses are significant, consider this: Can you imagine trying to trace your US ancestors without any federal censuses between 1790 and 1910?

1890 Census Fires Summary

Records lost

1890 US census population schedule (62.6 million names) and most special schedules

What survived

About 6,300 names from 10 states and Washington, D.C.; as well as Civil War veterans schedules for half of Kentucky, states alphabetically following Kentucky, Oklahoma Territory, Indian Territory, and Washington, D.C.

Where to look

Find surviving schedules at major genealogy websites, including Ancestry, FamilySearch, Findmypast and MyHeritage.

Substitute records

City directories, tax lists, state censuses and other records created between 1880 and 1900; see the 1890 Census Substitute database at Ancestry. Find tips for reconstructing the 1890 census here.

Tip: Use the 1900 and 1910 census columns for “children born” to a woman and her “children still living” to help determine whether you’ve missed any children born after the 1880 census who died or left home before 1900.

Read next: The Ellis Island Fire

ADVERTISEMENT