Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Courthouse Fires and Burned County Records

Those tracing US ancestors inevitably will come across the discouraging term “burned county.” It refers to places that have experienced courthouse disasters, whether fire, flood or weather. Records in county courthouses have fallen victim to destructive acts over the years. We’re delving into the Hamilton Country Courthouse Fire and the Great Chicago Fire, and sharing information on the lengths that counties go to in order to restore lost information.

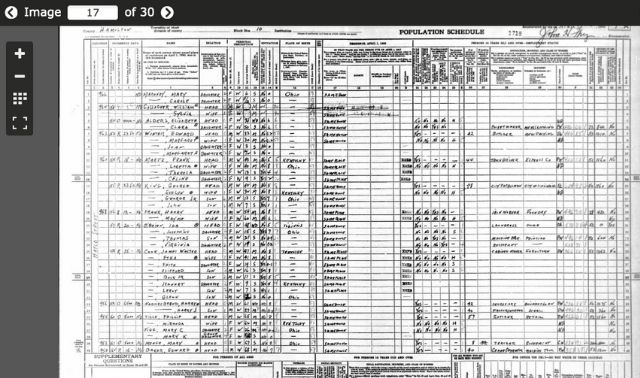

1802–1884: Hamilton County (OH) Courthouse Fires

One of the unluckiest counties for courthouse disasters has to be Hamilton County, Ohio—home of the “Queen of the West” city Cincinnati. Fed by Ohio River traffic, German immigration and an early 1800s meat-processing industry, Cincinnati grew into one of the first major cities of the inland United States.

The county’s first courthouse was a log cabin near a swamp. Locals must have been relieved when a two-story limestone brick building replaced it around 1802. But it only survived a decade. Soldiers billeted at the courthouse during the War of 1812 accidentally burned it to the ground.

The third Hamilton County courthouse was built on the outskirts of town. But that didn’t keep it safe. In the summer of 1849, sparks from a nearby pork-processing house landed on the courthouse’s exposed wooden rafters. A devastating fire ensued.

The county hired a nationally renowned architect to design a massive fourth courthouse building. By 1844, it housed one of the country’s leading law libraries. For the next 40 years, it seemed that the fire gods were finally smiling on the courthouse.

But nobody was smiling on March 29, 1884, after a jury returned a manslaughter verdict in the trial of a German immigrant. Seven witnesses testified that he’d described how he planned and carried out the murder of his boss. Locals thought the man should’ve been found guilty of murder, a more-serious charge. Police and Ohio National Guardsmen battled rioters storming the jail. The next day, a growing mob torched the courthouse and prevented firefighters’ efforts to put it out. It took 2,500 more guardsmen and another two days to quell the violence. The riots left more than 40 dead and 100 wounded, and another Hamilton County courthouse in ruins.

1871: The Great Chicago Fire

Another courthouse fire was part of a much larger conflagration: the Great Chicago Fire. When the Cook County, Ill., courthouse burned in the early morning hours of Oct. 9, 1871, no one was thinking about saving records. People were running for their lives. Well, everyone except for the unfortunate souls trapped in the basement of the courthouse—but we’ll come back to them.

The fire began about 9 p.m. in a poor urban neighborhood, in the barn belonging to Irish immigrants named O’Leary. Postfire rumors blamed Mrs. O’Leary’s cow for kicking over a lantern during milking. Historians have refuted this, with most instead pointing to young men playing dice. Chicago’s city council officially absolved Mrs. O’Leary in 1997.

Whatever the cause, wind quickly whipped the flames into a wall 100 feet high. Someone began tolling the courthouse bell as the blaze spread over downtown Chicago. Sparks landed on the wooden cupola of the courthouse sometime after 1 a.m., igniting the building. Panicked prisoners trapped in their basement cells cried out and pounded on the walls. Bystanders tried to free them, but were restrained until the mayor could send a hurried message allowing their release. With a few of the most dangerous criminals left under guard, the rest disappeared into the glowing night.

About 2:30 a.m., the heavy bronze bell that had been ringing for more than five hours crashed to the ground. When the last flickers of the Great Chicago Fire died 24 hours later, more than 2,000 acres of downtown Chicago had burned. Three hundred were dead and a third of the city’s population was homeless. The limestone courthouse was gone, along with all the records inside: vital records, court records, deeds and more. Recordkeeping begin again the next year.

Working around a “burned county”

Courthouses and other county repositories across the United States have suffered fires, floods, tornadoes, earthquakes and even cleaning frenzies by well-meaning officials. The Civil War in particular took a toll on Southern states. Union troops burned 12 courthouses to the ground in Georgia, for example, and 25 Virginia counties have Civil War-related losses of records.

Because fires may have spared some records in a “burned county,” always double-check whether the ones you need survived. Even if they didn’t, all may not be lost for your research. Court records have legal implications, so local officials would go to great lengths to restore the information. This includes asking residents to re-record their marriage licenses, wills and deeds. Genealogists might reconstruct lists of births and deaths from newspapers, cemetery records and other sources. Local government offices and genealogical or historical societies can help you learn about any surviving records and substitutes.

Burned County Records Summary

Records lost

Court records such as deeds, probate files, marriage licenses, vital event registers and trial documents

What survived

Varies

Where to look

Consult local research guides, county officials, and local historical and genealogical societies

Substitute records

Re-recorded deeds and other documents; delayed birth certificates; and local records not kept at courthouses, including church records, newspapers, town or township records

Tip: Research plans are helpful when working in a burned county. Note the specific record needed, then (once you’ve verified it was destroyed) list all the records that might provide the same information.

Return to: The 1890 Census Fires

Return to: The Ellis Island Fire

Return to: National Personnel Records Center Fire

A version of this article appeared in the May/June 2018 issue of Family Tree Magazine.