Every year in courts across the United States, immigrants promise to renounce foreign allegiances and support and defend the Constitution and laws of the United States. The Naturalization Oath of Allegiance to the United States of America is the culmination of a path that begins years earlier—applicants must meet certain residency requirements, demonstrate they can read and write English, complete an interview, pass a civics test and file a series of forms with US Citizenship and Immigration Services.

Our ancestors, while perhaps not having to supply quite as much documentation, also had to meet a set of requirements in order to become citizens. The naturalization documents filed in various courts throughout the process can help you track down family history clues.

In this guide, we’ll cover the historical citizenship process and how to find naturalization records.

The Naturalization Process

The process of naturalization generally involved declaring an intent to naturalize, waiting a specified amount of time, then filing a petition to naturalize. After a hearing, a judge would grant the successful applicant a certificate as proof of citizenship. Laws governing the waiting period and required length of US residency varied over time.

The first naturalization law, passed in 1790, allowed free whites who’d lived in the United States for two years and the same state for one year apply for citizenship. In 1795, the residency requirement was increased to five years, and applicants had to give three years’ notice of their intention to naturalize before they could become citizens. A 1798 law, repealed in 1802, increased this to 14 years’ residence and five years’ notice. In 1824, the waiting period after declaring an intent to naturalize was reduced to two years.

Until 1922, women rarely applied for naturalization in their own right; instead, they became citizens when their husbands naturalized. After 1922, an alien woman who married a US citizen could skip the declaration of intention and file a petition for naturalization. But if an alien woman married an alien man, she’d have to start her naturalization proceedings with a declaration of intention; see the Summer 1998 issue of the National Archives’ Prologue Magazine for more details on women and naturalization.

Prior to 1906, immigrants could file for naturalization in any court at the local, county, state or federal level. He might go to the next county’s court if it was closer, or file in a big city court before heading West. Some people even filed in criminal or marine court. A person could even begin the process in one court and finish it in another. A variety of forms were used for those naturalizations, so the information recorded varies from court to court and from year to year.

In September 1906, the Basic Naturalization Act turned the naturalization process over to the Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization. (The Bureau later became the Immigration and Naturalization Service, or INS, which in turn became the US Citizenship and Immigration Services, or USCIS.)

This act standardized the process of becoming a citizen. After 1906, naturalization papers were supposed to be filed in certain federal courts, although some local courts continued to process naturalizations well beyond that date. In addition, from 1906 on, forms filled out about the applicant were standardized. For more about the history of naturalization, consult our timeline of US immigration laws.

Types of Naturalization Records

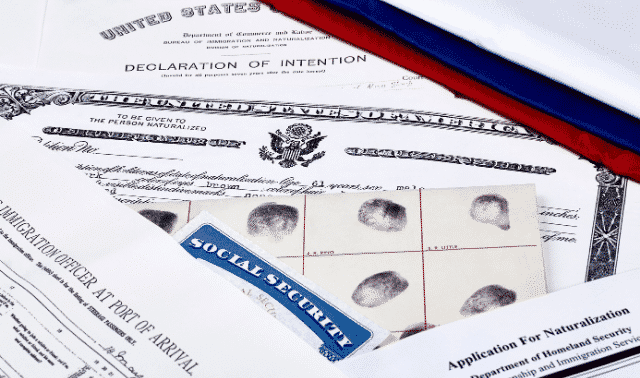

Each step in the citizenship process produces its own set of documents. The three created for most naturalized citizens are the declaration of intent, petition for naturalization, and certificate of naturalization. In some cases, other records also might have been generated.

Declaration of intention (or first papers)

With this record, an alien declares his intention to become a US citizen and renounces his allegiance to foreign governments. Declarations of intention filed before Sept. 27, 1906, usually contain bare-bones information:

- applicant’s name

- applicant’s country of birth or allegiance (but not the specific town)

- date of the application

Declarations of intention filed after Sept. 27, 1906, provide additional details, including:

- more-specific birthplace

- port and date of arrival

- physical description or (from 1929 on) photo

- names of a wife and any children naturalized along with the husband

The declaration of intention requirement ended in 1952, although immigrants still have the option to file a declaration if they want to.

Tip: Immigrants who filed the declaration of intention sometimes didn’t complete the citizenship process before the declaration expired. Thus, you may find multiple declarations for one person.

Petition for naturalization (or second/final papers)

Once a person declared his intention to become a citizen, met the residency requirement and waited the required period after filing, he could submit a naturalization petition to the court. He often filed in the court closest to where he lived.

Starting in 1906, second papers typically include:

- petitioner’s name (possibly his birth name) and any name changes

- residence

- occupation

- birth date and place

- prior citizenship

- personal description

- date of arrival in the United States and arrival and departure ports

- date when US residence commenced and length of residence in the state

- marital status (listing wife’s name and date of birth, if married)

- names, dates and places of birth and residence of the applicant’s children

Certificate of naturalization

After the applicant completed the citizenship requirements and signed an oath of allegiance (a record usually found along with the petition), a certificate of naturalization was issued to the immigrant. Most certificates contain the individual’s name, certificate number, name of the court where he filed and date issued.

The government didn’t retain copies of these certificates, so the best place to find them is among family papers.

Naturalization depositions

These documents contain statements made during a naturalization hearing by witnesses in support of an applicant’s petition.

Certificate of arrival

After 1906, courts began to require proof that an immigrant had legally entered the country. It was provided in the form of a certificate of arrival, which listed the port name, date and ship of the immigrant’s arrival.

A clerk at the immigrant’s stated port of entry would locate his passenger list to verify the date and ship of arrival, often making a notation on the passenger list. The INS would then issue a certificate of arrival and send it to the naturalization court. Certificates of arrival were first issued under the Basic Naturalization Act of 1906; a 1929 law mandated them for every naturalizing immigrant. These certificates are generally included in a naturalization records file.

Alien registration files

In 1940, the Alien Registration Act required all noncitizens age 14 and older living in the United States to register. Each registered alien was assigned an Alien Registration Number, or A-number. The registration form, part of the immigrant’s Alien File (A-file), requested a broad array of detail including all names used, date and place of birth, immigration date and ship, activities and organizations, criminal history and more.

Clues to Naturalization

Not every immigrant filed for citizenship. The following sources can provide clues to whether an ancestor filed and when he achieved citizen status:

Censuses

US censuses in 1870 and 1900 to 1950 include notations about whether a person was naturalized. The year of naturalization is given in the 1920 census. Look at the citizenship columns for the following abbreviations: AL (alien), NA (naturalized), NR (not reported), PA (first papers filed), IN (declaration of intention) and Am Cit (American citizen born abroad).

Immigration records

Examine your relative’s entry on an immigration passenger list for annotations regarding nationality and citizenship. A number, perhaps with the note Naturalization Certificate Number, indicates a clerk checked the list to verify the person’s legal arrival.

If a naturalized citizen traveled abroad on business or to visit family, the passenger list documenting his return would have a notation such as USC (for US citizen), Nat, Natz or Naturalized. For more information on passenger list notations, see JewishGen. Finally, a naturalized citizen who applied for a passport would note his year of naturalization. Look for passport records on Ancestry.com, Fold3 and FamilySearch.

Voter registration records

After 1906, an immigrant had to be a citizen in order to vote. Voting records vary in availability and location. Check county or city repositories, local libraries, and historical and genealogical societies.

Land records

Immigrants had to file at least a declaration of intention before they could apply for land under the Homestead Act of 1862. At the end of the five-year term, when the immigrant went to secure the patent to the homestead, he had to have become a citizen. Therefore, homestead applications may contain copies of naturalization records.

You can obtain these files from the National Archives, the appropriate state’s Bureau of Land Management office or from the county courthouse. If your ancestor was successful in obtaining the homestead, finding the land patent should make it easier to get the homestead application records.

Military records

After 1862, aliens who served in the US Army and who were honorably discharged could apply for citizenship on an abbreviated timeline. This didn’t guarantee citizenship, however. The military service record isn’t likely to contain the naturalization record, but if the veteran applied for a pension, you may locate documentation there. WWI draft records indicated naturalization status as well; find digitized draft cards on Ancestry.com, Fold3 and FamilySearch.

Finding Naturalization Records

Finding your ancestor’s naturalization records has become easier with the internet age. You should have a good idea of when your ancestor filed and where he lived at the time, because record collections are largely organized geographically, and this information will help you identify the right record. But you’re spared needing to know which court he used, visit in person or obtain microfilm (though we’ll cover how to do the latter, too). Here’s how you can find the records.

Online

Start by searching naturalization collections on websites including subscription-based Ancestry.com and Fold3 (look for the Non Military Records collection), and the free FamilySearch. Your library or local FamilySearch Center may offer access to subscription collections, and/or you can use Ancestry.com’s free World Archives Project index to “U.S., Naturalization Records, 1840–1957.” You’ll need to choose a collection based on where your ancestor lived.

Search these sites for a name, then narrow your search as needed by place, year and collection. An immigrant may be naturalized under his birth name, rather than an Americanized name used in later records.

On FamilySearch, online collections include mostly naturalization filings in federal courts and state superior courts. If you find a result in an index-only collection—one without an attached image of the naturalization document—use the source information provided in the index entry to seek a copy of the record on microfilm or by mail.

If your ancestor filed for naturalization before 1906 in a county court, you still might find records among FamilySearch’s digitized court records. Many of these collections aren’t indexed, so you can’t search by name. Instead, go to the Historical Records Collections page and use the filters to choose United States of America, then the state. Look for court records from your ancestor’s county in the collection list, sorted by record type. Ideally, there’ll be a naturalization index book you can search to find the volume and page number with the record you need.

Some county courts, libraries and genealogical societies have put naturalization records or indexes online, such as Cook County, Ill., (home to Chicago) and Hamilton County, Ohio (home to Cincinnati). Try a web search for your ancestral county, state and the words naturalization records genealogy. If you have success in an index, be sure to look for copies of the records.

For a state-by-state overview of online naturalization records, check Joe Beine’s Online Searchable Naturalization Records and Indexes.

Offline

If your online search doesn’t pan out, you’ll need to check microfilmed records for the court where you think your ancestor filed for naturalization, visit the courthouse or send a written request.

County courts and state supreme courts are the most common locations for naturalization filings, but they also could have been filed at a circuit, district, probate or common pleas court. The Red Book: American State, County, and Town Sources, part of Ancestry.com’s research wiki, offers summaries of court records available each state.

Before you visit a courthouse, check the website or call ahead to ask about locations of historical records and research rules. Otherwise, look for microfilmed court records in the FamilySearch online catalog.

Declarations of intention and naturalization petitions filed in federal district courts before and after 1906 are on microfilm in the National Archives research facility covering the area of filing and through FamilySearch.

USCIS Genealogy Service

Naturalization records after 1906 are available online and on microfilm with the above resources, but you also can order copies through the USCIS Genealogy Service. The USCIS is the only source for alien registration records and naturalization case files (C-Files).

You’ll first request an index lookup for the file number(s) needed, then order copies of the file(s). This is a fee-based service (whether or not a record is found) and the wait is 90 days or longer. So first try the resources mentioned above if possible.

Clues in Naturalization Records

If you’re looking for an immigrant’s name at birth, place of birth or arrival date, you might find what you need in his naturalization records. Although earlier records might provide only the country of birth, post-1906 records usually provide enough detail to help you find passenger records and launch your research in your ancestral homeland.

Even early records name witnesses who swore to your ancestor’s good character and legal arrival on US shores. In later records, witnesses are named on the immigrant’s oath of allegiance. Always note the names of these witnesses, because they may be family members or at least give you a picture of your ancestor’s social circle. Your ancestors also may show up as witnesses on naturalization applications of their relatives, friends, neighbors or co-workers.

Finally, post-1906 records name the applicant’s immediate family and sometimes give their addresses, helping with your collateral research efforts. Records before that rarely name family, even when a man’s wife and children became citizens by virtue of his application.

Sample Records

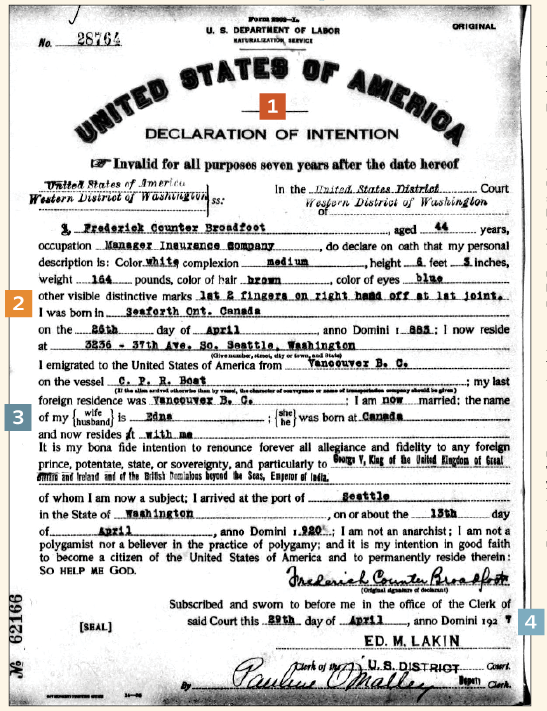

Declaration of Intent

- Immigrants across the United States used this standard form to declare their intention to become citizens.

- Details in post-1906 declarations usually include a specific place of birth and a physical description. The description of Frederick’s injury may help identify him in other records.

- A married applicant provided the spouse’s name and birthplace.

- In 1927, immigrants intending to naturalize had to wait at least two years after filing a declaration of intention to file a petition for naturalization.

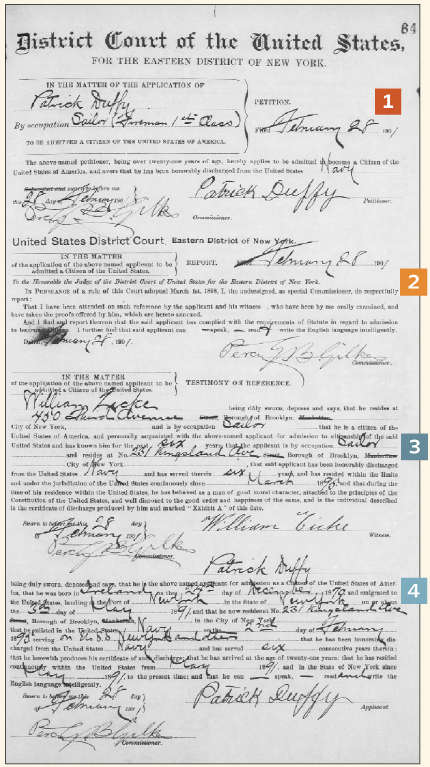

Petition for Naturalization

- The top section of this 1901 document records the name of the applicant, Patrick Duffy, his military service and the filing date. Beginning in 1862 for the Army and 1894 for the Navy and Marines, those honorably discharged from military service could skip the declaration of intention and fulfill a residency requirement of just one year.

- In this section, the commissioner testifies that he has examined the applicant and witness, and found the applicant has satisfied the requirements of citizenship.

- A witness’ address, signature and testimony on his familiarity with the applicant’s moral character and fulfillment of the residency requirement are included.

- Personal information is limited in petitions filed before Sept. 27, 1906, but this one provides the name and address of the applicant, date and country of his birth, date and port of arrival, and US military enlistment and discharge dates are listed. This can help you find the right Patrick Duffy in passenger lists.

Related Reads

Versions of this article appeared in the September 2015 and May/June 2023 issues of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: September 2024