Explorers first mapped North America half a millennium ago. Over the following 300 years, armies charted roads and rivers, forests and forts. Surveyors later partitioned large tracts and land offices gradually sectioned them into properties. Maps’ edges crawled westward—sometimes with imagined details—as the population grew and migrated.

By the 19th century, maps showed more than bird’s-eye views. Topographic maps captured landforms and bodies of water. Insurance maps sketched out buildings and neighborhood blocks. Cartographers mapped distributions of the general population, ethnic groups, diseases, crops and weather patterns.

More-precise maps became available as imaging took flight. Aerial photography by the US government began in the late 1930s, and later was supplemented by high-altitude aircraft and satellite imagery. In the last 30 years, satellite imagery, global positioning and geographic information technologies have together charted the most accurate images of the world ever made.

Today many of these map images—old and new—are available on the internet. Also online are other geographical tools that help us explore our ancestors’ worlds. But what can you do with online maps, besides mark an X where an ancestor lived? These five powerful ways to use online maps will help you solve research problems, find new records and envision your ancestors’ world.

1. Confirm Boundaries

Did your ancestors live where you think they did? Maybe not, if you’re looking up their residence on a modern map. “Modern maps hide a lot of historical secrets,” says Robert Davis, professor of genealogy, geography and history at Wallace State Community College in Hanceville, Ala. “For example, when Alabama Territory was created from Mississippi Territory, Washington County was split down the middle. This created a Washington County in each territory. These counties each changed over time.”

Why does it matter? Because the jurisdiction—especially the county—is where you look for your ancestors’ genealogical records. Let’s say you started researching a family from Houston County, Ala., which didn’t exist before 1903. Before that, the area belonged to Henry County. And before Alabama became a state in 1819, the area that’s now Houston County belonged to several other territorial jurisdictions at different times—including Washington County, Mississippi Territory.

You’ll find a quick interactive map guide to national, territorial and state boundaries here. Then, head to The Newberry Library’s Atlas of Historical County Boundaries. Click on a state, then on the View Interactive Map link to see county boundaries on any given date (down to the day!), or click to read descriptive summaries of boundary changes.

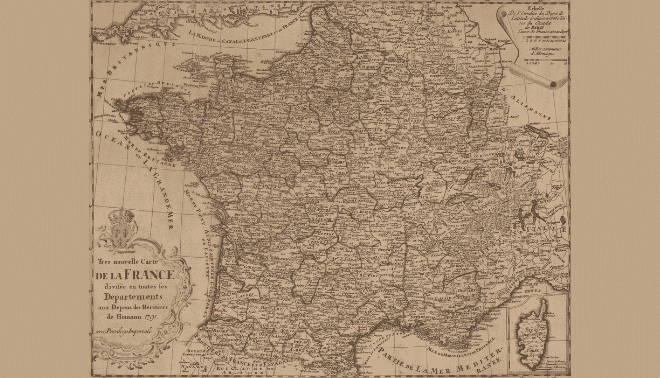

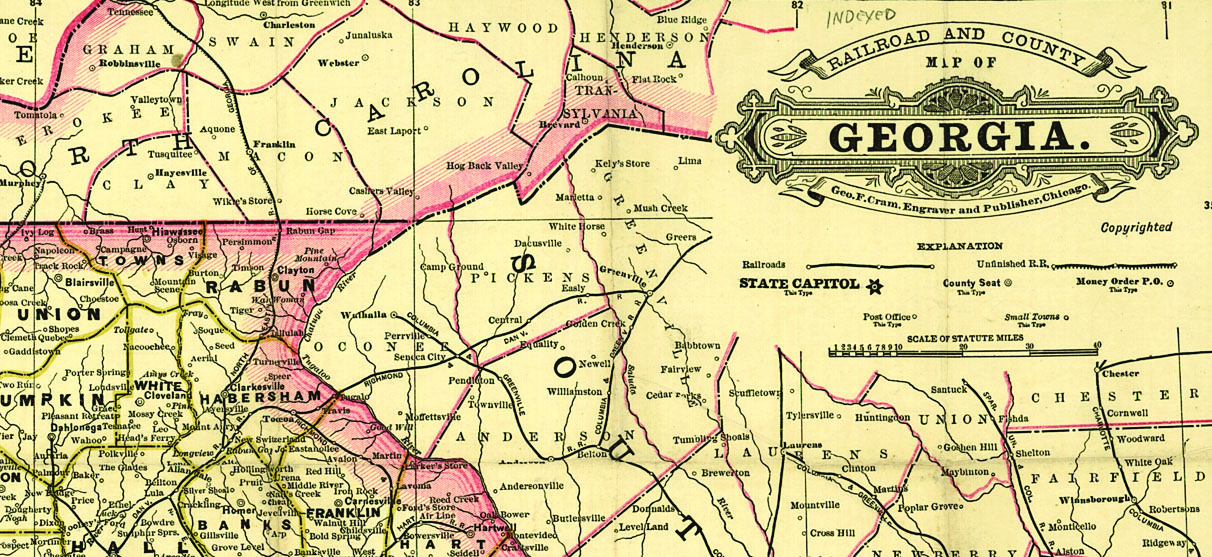

You also can consult the old maps several states commissioned in the 1800s. “These are monster county-by-county maps, like the size of a pool table,” Davis says. “The earliest for Georgia go back to 1780; in South Carolina it’s even further. This was en vogue until about the 1880s.”

“In many cases, the publishers outlined the maps, then sent them to local county commissioners to fill in the details,” he continues. “Most don’t show individual farms but they do show main roads and post offices. Some state archives or university libraries have put these online.”

Davis recommends contacting state archives to see what exists and what’s online; collections vary by state. Look for links to digitized state maps at the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection and MapofUS.org online directories.

Old maps and charts also are published in regional atlases. Sometimes atlases include local histories and biographies of prominent citizens, pictures of buildings, statistical data, military memorials, schools, churches and more. Search for digitized atlases at the David Rumsey Map Collection, on state archive and university library websites, and on sites such as Google Books.

Davis cautions that, especially on the frontier as people migrated westward, some folks didn’t know or care (or care to admit) where they lived. “In North and South Carolina, there was no official boundary until the 1820s,” continues Davis. “For close to 100 years people didn’t clearly know which side they lived on. They were sometimes skipped by census takers. They would tell the tax collector from one state that they lived on the other side. It was a matter of whose opinion you believed.”

Other kinds of boundary changes may affect your research, too. Local records may have been kept within voting or military districts (such as precincts or draft boards), which may be mapped on state and county genealogy websites. Catholic and Episcopal sacramental records may be at diocesan archives if they’re no longer with the parish church. You can identify the modern diocese with online parish locator tools, and then search for old maps or boundary descriptions for that diocese.

2. Survey the Neighborhood

Whether your family lived in the city or countryside, maps and aerial images can teach you a lot about their daily lives. How did the natural landscape help or hinder their lives? How far away was shopping, work and school? Were they nestled with or isolated from the neighbors? Five kinds of maps can provide clues to help you picture your ancestor’s locale.

Topographic maps

These maps will help you imagine the view out an ancestor’s front door—and how arduous it was to get around. Topographic maps show land elevation, waterways and even manmade landmarks. The US government began creating topographic maps in the 1880s.

“Anything that shows up on a federal topographical map tends to stay there forever, even if there’s nothing there now,” says Davis. This includes cemeteries, churches, roads and other local landmarks. “Roads especially change less than people might think. Engineers put roads in the same places for the same reasons over the centuries.”

Start topographical research with the easy-to-use USGS Historical Topographic Map Explorer. Also use the desktop version of Google Earth.

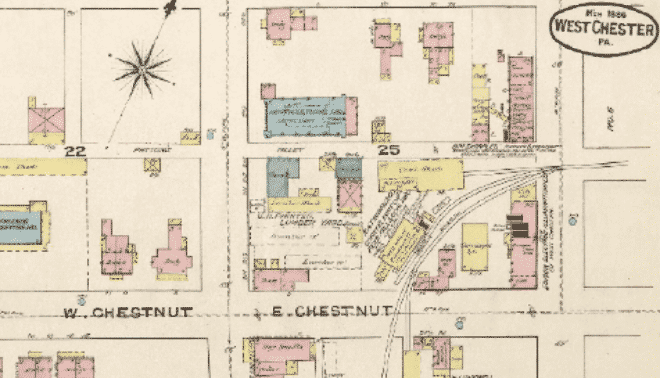

Fire-insurance maps

These maps capture a different kind of landscape: city streets, alleys, factories, churches, homes, outbuildings and more. They’re great for house history research, says professional house historian and genealogist Marian Pierre-Louis. “If you know the location of a house, Sanborn maps can be helpful to verify the existence of the property and to get a feel for its size and construction materials.”

For example, you might learn that an ancestor’s apartment building had asbestos in the basement and two windows per three-room unit. Or you might learn that the home on your relative’s lot was made of brick and had a stable out back. Sometimes property owners were identified, too, especially for commercial properties. The warehouse or factory in which a relative worked might be described in detail.

Look for Sanborn (the biggest publisher) and other fire-insurance maps for urban areas beginning in 1867, and for most US cities and towns by the early 1900s. The Library of Congress has the largest collection of digitized Sanborn maps. Also search for maps in the ProQuest Digital Sanborn Maps collection (1867–1970), which may be available at your local library. Some public, state and university libraries have digital fire insurance map collections, such as the Cincinnati and Hamilton County public libraries.

Military maps

“During the Civil War, opposing armies drew exceptionally detailed maps that include farms, roads, churches, creeks, roads and paths,” to plan troop movements, says Davis. If you know your ancestor’s military unit, you can use a battlefield map and battle reports to trace his whereabouts. The Library of Congress Civil War map collection is online. The resources at the American Battlefield Trust also can help you follow battlefield action.

Panoramic maps

These maps “provide a close up view of a city, mostly for 19th-century locations,” Pierre-Louis says. While not true-to-scale maps, these show a city’s layout from a unique perspective. They’re also known as bird’s eye view or perspective maps. You’ll find a digitized collection with maps dating from 1847 to 1929 at the Library of Congress.

Demographic maps

Also called thematic maps, demographic maps date back to 1790 and are usually created from US census data. They’ll show distribution and changes in population, agriculture, housing, race and ethnicity, and more. Not only will these maps give you a glimpse of your ancestor’s changing world, but they can provide clues to migrations (perhaps he was part of a large population shift among his ethnic group?), economic status and more. Several demographic maps appear in The Family Tree Historical Maps Book by Allison Dolan (Family Tree Books).

Not exactly maps but neat nonetheless, aerial photos may be another helpful source. “I use them all the time in my research,” Pierre-Louis says. Vintage Aerial has more than 25 million photos from 41 states since about the mid-1900s.

3. Find Ancestral Addresses

It’s exciting to find the names of ancestral hometowns in old letters, census records, city directories, draft registrations, deeds, land patents, government benefit applications and more. But locating exact addresses for an ancestral home or business on a map isn’t always as easy as marking X on the spot.

“Addresses as we know them today are a modern construct,” Pierre-Louis says. “ZIP codes weren’t introduced until 1963. Prior to that, while street addresses were preferred, mail could be sent to simply a name in a specific town, and still arrive there.”

Duplicate town and county names can be your first big problem. “In Georgia, we name towns and counties after our heroes,” Davis says. “This creates a lot of duplicates. Did your relative live in the city of Macon, Ga., or the county of Macon, Ga., 100 miles away? There are over 30 instances of cities and counties with the same name in Georgia alone.”

To locate ancestral homes and businesses, consult the Geographic Names Information System (GNIS), a database of current and historical US place names (along with their locations). If you click on Search Domestic Names, enter Springfield in the Name box, and select Wisconsin from the Feature State dropdown menu, you’ll find several places (civil administrative divisions and “populated places”) called Springfield, including those known as Springfield in the past.

The GNIS is an online version of a geographical dictionary or gazetteer. Gazetteers exist for many counties and states. Many are online, such as the 1795 Gazetteer of the United States by Joseph Scott in the David Rumsey Map Collection and 1797 American Gazetteer by Jedidiah Morse at Internet Archive. Gazetteers also are useful for pinpointing a place of origin in ancestral homelands, which also are prone to duplicate place-names.

The 1912-1913 edition of Meyers Orts- und Verkehrs-Lexikon des Deutschen Reichs (Meyers Gazetteer of the German Empire; Meyers Orts, for short), a go-to resource for German researchers, is available on Ancestry.com. The Topographical Dictionary of Ireland, published in multiple volumes in the 1840s, is digitized on FamilySearch Books. Keep in mind that gazetteers will usually be in the language of the region they describe.

What about street names and numbers? Pierre-Louis says these got an earlier start in cities. “Numbering in rural areas with smaller populations was less important.” She cautions, however, “It’s very likely that many addresses [before 1900] might have changed or the streets were renumbered during the 20th century.”

This is particularly true for large cities. Local genealogy research guides can be helpful here, as can a web search for the city name and the phrase “street name changes.” City directories published around the time of street name changes and renumberings may describe the updates in front or back matter, and deed records for properties on a street may identify a prior name. Alternatively, compare street names and layouts on old and newer maps. You can do this using the map overlay feature in the free Google Earth; find a tutorial on using historical maps in Google Earth.

4. Plot the Family Property Lines

Mapping an old piece of your family’s land—or even the entire neighborhood over time—can help solve genealogical problems and open up possibilities. “Sometimes you can visit that place today; maybe you’ll find some chimney rocks or family graves or even the old house, if nobody tore it down,” David says. “Of course, you might find it’s now a parking lot.”

Adjacent landowners to your ancestors, previous and later landowners, or individuals you find selling off pieces of the family land might also be kin. Because people often courted and married those who lived nearby, consider neighbors’ surnames as possibilities for a female relatives’ maiden name. And you may be able to distinguish families of the same name by tracking their landholdings—no two people could own the same land.

Old deeds describe property boundaries in different ways: using the metes and bounds system; using the rectangular survey system (aka the public land survey system); and by numbered lots.

Metes and bounds

The metes and bounds system was common in the original Colonies and states formed from them. It relies on the land’s natural and man-made features. The description starts in one corner of the land parcel, and then traces the perimeter in sections. It may reference old-fashioned measurements, such as rods and chains, and obsolete landmarks, including fence lines and trees.

Online tools can help you draw these property descriptions. Find free plot platters such as Plat Plotter. More sophisticated software is available for purchase, like DeedMapper for Windows and Metes and Bounds (Mac, Windows, iOS and Android).

Next, find a reference point, such as a river, that helps you place the property (or even an adjoining parcel) on an old or new map. Not working? Follow the land ownership forward in time, both by deeds and on maps. Later deeds may update the description to something you’ll understand. Later maps may show it more clearly (and the deed history will help confirm it’s the same piece of land).

Rectangular survey system

If your ancestors purchased land from the federal government, the plot is likely described in terms of townships, ranges and sections. Townships were gridded off by north-south and east-west reference numbers. Sections were divided into halves and quarters. Aliquot parts (property descriptions) may be abbreviated as “SW¼ SE¼ S3 T38N R16W,” which means it’s in the southwest quarter of the southeast quarter of section three of a township, which was located 38 tiers north of a base line and ranging 16 rows west of a meridian.

Look up land patents (and map townships and sections) at the Bureau of Land Management General Land Office Records website. Map lands in further detail at Earth Point. Click the Search By Description tab and enter the coordinates. Then click Fly To On Google Earth to see the property mapped out there. (If a KML file is generated, click here for instructions on how to open in Google Earth.)

Numbered lots

In developed neighborhoods, you may find deeds describing numbered lots and, sometimes, street addresses. Plug any street addresses into Google Earth to “fly” right to that address today—if it hasn’t changed. If you find an address on Google Earth, look for old neighborhood maps in the Historical Maps overlays, or search for them in online map collections.

Confirm the location by looking for lot numbers on neighborhood or subdivision plat maps, which show property boundaries and owners’ names. Pierre-Louis says that plat maps can date to early times in New England and in states without federal land sales. Original maps may be on file in local town or county offices or, rarely, online at a county auditor’s website.

You also can compare the lot descriptions to any maps you do find online. Pierre-Louis suggests checking the Historic Land Ownership and References Atlases collection on Ancestry.com, a collection of historical maps and atlases from 1507 to 2000.

5. Identify Migration Paths

Is the Obadiah Burdock who suddenly shows up in Oregon the same as your Obadiah Burdock who disappears from Iowa around the same time? Piecing together the travels of our ancestors is easier when we consider their paths of least resistance: established migration routes. “Following common migration patterns seldom serves me wrong,” says Davis. “For every person who came to one particular place from one area along the coast, there may have been a thousand people who came from another particular county.”

Regional histories often indicate whether folks mostly traveled by road, river, sea, canal or rail in that time and place. For example, Davis says, “In Virginia, the rivers were everything, and a traditional Southern family moved south out of Virginia until they got to Georgia, and then they moved west.”

Several online resources can help you identify common migration routes. Start with the American Migration Patterns website. At RailsandTrails.com, you can find old rail routes between cities and even timetables. Davis warns that these routes are just possibilities, though. “The Great Wagon Road wasn’t one road: It was several roads and was traveled at several different times.”

The counties of birth of a family’s children can help you follow where they moved. Find these counties on maps published around the time of the birth. “When you plot out where the children were born, the map tells the story,” David says. “You can see they’re moving in the same direction as the river flows.”

When you learn a migration route, you may discover records generated along the path; these are like documentary breadcrumbs. For example, wagon train lists exist for many western trails and so do travel diaries kept by fellow travelers. Explore them at sites like Paper Trail.

Railway passenger arrivals sometimes were mentioned in local newspapers, which also advertised letters left for travelers. To find names and publication dates of newspapers across the country, use the Chronicling America newspaper directory. Also search digitized historical newspapers on subscription sites GenealogyBank, Newspapers.com or Ancestry.com. You can learn about orphan train riders’ documents at OrphanTrainDepot.org (click NOTC Research > Research Resources).

Before the days of rail travel, a family might have migrated very slowly. Years may have passed before immigrants left the city where they arrived in the United States for parts inland, and they may have settled for a time in towns along the way. Search for relatives all along the migration path in digitized sources such as censuses and newspapers. Use ArchiveGrid and online catalogs of individual archives to search for original records—like church records and business ledgers—from each locale.

Just as early mapmakers gradually filled in the gaps on old maps as they explored each new territory, so can we use online maps and mapping tools to fill in gaps of knowledge about our ancestors. They’ll help us plot more accurate research courses and fill in the contours of their lives. So get online and start googling—and then ogling—these images from the past.

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the March/April 2015 Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: May 2025