As researchers, we have our favorite go-to’s. We tend to get set in our ways and continue down the same paths. But sometimes, consulting the same records and making the same assumptions means we end up with the same result: a brick wall.

Notably, as soon as we have a new lead or a new ancestor’s line to research, we jump right to the federal population census. The federal census, as we know, is taken every 10 years, but it also contains numerous inaccuracies and isn’t a foolproof source.

For one thing, there’s the issue of the 1890 census. We often hear the returns are missing and make assumptions. We run! We expect a huge loss of information and records, and jump right to the 1900 census.

Why do we do that? There are 20 years between the 1880 and 1900 censuses. Do we really think nothing was going on in our ancestors’ counties and communities during that time? No one is beyond having brick walls or research challenges, but let’s not create our own by simply giving up.

Instead, we can change our thinking and reframe record-loss events like the 1890 census as challenges that can be overcome. I now teach the three E’s of challenges in genealogy. We:

- Expect them

- Embrace them

- Let them enhance our research skills

Take them as an opportunity to find another way to get the information you need, and to go “back to the basics” of genealogy research: researching a time and place, and asking the right questions. There’s no magic in conducting genealogical research—just deeper dives!

So how can we deal with the challenges of not having the 1890 census? Years ago, I developed “Murphy’s tips,” five factors that researchers should consider when studying ancestors: the Money, the Land, the Water, the Community and the Faith of the people.

Each of those five generate records that can provide valuable genealogical information, since (at any given time) people are still being born, dying, getting married, getting divorced, buying and selling land, and (of course) paying taxes.

Let’s take a deep dive into what information the 1890 census contained, and what kinds of “substitute” records can provide us with the same details. As we’ll see, with the right attitude, we are likely not missing much information from the 1890 census after all.

Understanding the 1890 Census

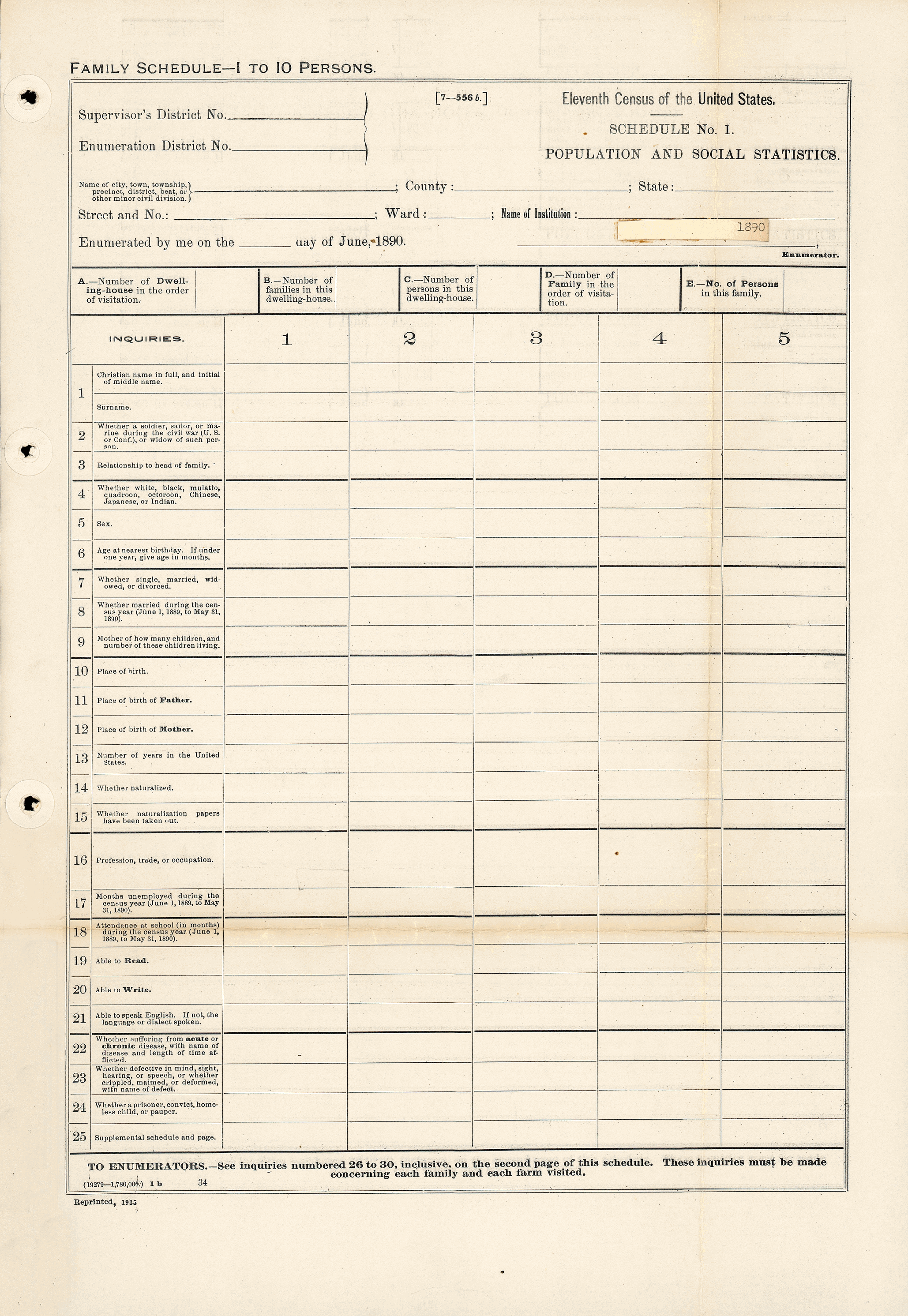

A critical way of handling a records-related challenge is to review the document’s contents, as well as the record-keeper’s intent. Like in other federal censuses, paid enumerators asked residents specific questions, and were given instructions on how to handle various responses. You can view and download enumerator instructions for the 1890 census at Census.gov.

1890 census questions

Below are the 25 questions asked of each respondent in the 1890 census. You can view the original form here:

- Name

- Civil War veteran or widow status

- Relationship to the head of the family

- Race

- Sex

- Age

- Marital status

- If married within the last year

- Number of children, and how many children are living

- Place of birth

- Father’s place of birth

- Mother’s place of birth

- Number of years in the United States

- Naturalization status

- Whether naturalization papers have been filed

- Profession, trade or occupation

- Number of months unemployed in the past year

- Number of months attended school in the past year

- Able to read

- Able to write

- Able to speak English, or what other language/dialect is spoken

- Is the person suffering from an acute chronic disease? If so, what is the name of that disease and the length of time affected?

- Is the person defective of mind, sight, hearing, or speech? Is the person crippled, maimed, or deformed? If yes, what was the name of his defect?

- Is the person a prisoner, convict, homeless child, or pauper?

- Supplement schedule and page (if questions 22–24 require additional documentation)

The following questions were on page 2 and asked just once of each family or farm:

- Is the home rented (“hired”) or owned?

- If home owned, is there a mortgage on the home?

- Is the farm (if indicated) rented or owned?

- If farm owned, is there a mortgage on the farm?

- Address of home or farm owner, if property mortgaged

As you’ll see, enumerators asked a total of 30 questions. Some were demographic in nature or about families: Who is in the household, and how are they related? But others asked about land: Who owns it, is there a mortgage on the property, etc. Don’t forget about the second page, which has questions 26 through 30. These were asked just once of each family and farm visited.

In addition to the numbered questions, the top of the sheet provided organizational questions about the enumerator’s process and where the community was within the county or neighborhood. Letters A through E indicate number of dwellings in the order of visitation, as well as the number of families and persons within a dwelling.

Assessing what you already know

Once you’ve reviewed the census questions, ask yourself some questions. Which of those details do you already know about your family during that 20-year period? Consider the following:

- Are the individuals in the same place as they were in the 1880 population census? What about the 1900, or even the 1910 census?

- Do you have contemporary city directories, newspaper articles or other references that might have some information?

- Has anyone in the family died? If so, do you have the death record, obituary, etc., that will give you place, time and names?

- Has anyone married between 1880 and 1890?

- Was anyone in the family a soldier or veteran?

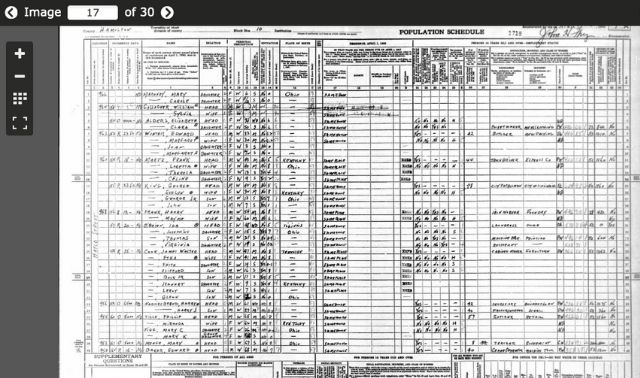

Keep in mind what questions were asked in the 1880 and 1900 censuses, as well. Some of the details will overlap with what was asked in the 1890 census. You can find a list of questions for all censuses (1790–2020) at Census.gov, as well.

Gathering Substitute Records

Now that you’ve assessed what information you already have, consider what documents could produce the details you still need. What other genealogical records provide the same information that was gathered in the 1890 census?

Birth records, for example, provide: name; birth date and place; parents’ names and maybe birth locations; and even possibly occupations. Death and marriage records often do the same—useful, since vital records may be available for the 1880–1900 period and earlier. Don’t forget to check vital records both for the subject of interest as well as their children.

States may have taken their own enumerations, including between the 1880 and 1900 federal censuses. Kansas, for example, took censuses in 1885 and 1895, and Michigan in 1884 and 1894. The details in them will vary, but your ancestors’ listings will still help you fill in that 20-year gap. (Family Tree Magazine has a list of state censuses.)

Other sources to consider include:

- School records for children

- Institutional records for those in hospitals, orphanages, prisons or insane asylums

- Church or religious records, such as baptisms, burials, confirmation/bar mitzvah records, and parish directories

- Community-specific censuses such as the Dawes Rolls taken of the “Five Civilized Tribes” (1898–1914)

- Local publications, such as newspapers, city directories, newsletters and quarterlies

- Organizational records from professional or civic societies

In addition, look to see if your ancestors were listed in the supplemental “Defective, Dependent, and Delinquent” (DDD) Schedules of the 1880 census. Separate schedules covered the incarcerated, the blind, the deaf, and those with mental illness or developmental disabilities. An ancestor’s presence in one of those lists may be a clue to look for them in institutional records from the era.

You might also consider creating a timeline of your ancestor’s life. For each event, ask yourself “So what?”—that is, what documentation might be associated with that milestone, and what ramifications it has on other parts of your research.

Re-Creating an 1890 Entry: A Case Study

Now that we’ve changed our thinking about the 1890 census, let’s try to locate more information about my ancestor Ahira H. Worden. Here’s what I already knew about him:

- He was born in Eaton County, Mich., the son of Parley and Lydoriana (Boyer) Worden.

- Ahira’s parents came from Rensselaer, Herkimer and Onondaga Counties in New York.

- Ahira married Elizabeth Boyer on 23 July 1859 in Eaton County, Mich.

- Parley and Lydoriana relocated from Eaton to Oceana County about 1860.

- Ahira wore some sort of medal in a photo, perhaps indicating Civil War service.

- Ahira and Elizabeth had an undetermined number of children, three of whom lived to adulthood.

- Ahira died in 1916 in Oceana County, Mich.

But, of course, I couldn’t find Ahira or his family in the 1890 census, which would have provided some of the information above. For example: Were he and Elizabeth in the same place from 1880 to 1900? Had anyone gotten married during that time span? And was Ahira a Civil War veteran?

To essentially re-create Ahira’s census entry, I would need to research more records. I hadn’t yet found him in the 1880 or 1900 censuses, nor had I consulted city directories or vital records for the family. But here’s what I was able to find in other documents:

- Birth records: Ahira’s son, Arthur, was born in Oceana County in 1882.

- Military records: Registration records on Ancestry.com revealed that Ahira (as well as his brother) registered for the Civil War in 1863 in Michigan. According to pension records, Ahira had been applying for a pension since 1881, but only had success in 1907. I obtained his pension file, which confirmed he lived in the same area and gave Elizabeth’s age as 70 when she took over the pension in 1916.

- Organizational records: I ran a Google search and discovered that Ahira was a member of his local chapter of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), a Civil War veterans’ organization. The medal I’d seen in his photograph was a GAR medal. Another Google search uncovered that the chapter was founded in July 1882.

- Federal censuses: The 1880, 1900 and 1910 counties verified Ahira was in Oceana County.

- State censuses: Ahira is listed by name in a statistical return of the 1894 Michigan state census.

- Obituaries: Thanks to the Oceana County Historical Society, I was able to obtain Ahira’s obituary, which included a birth date (20 March 1838). Parley’s 1862 obituary from the same source indicates Ahira and Elizabeth first came to the area in 1863.

Now we’ve gathered more information, let’s “respond” to the 1890 census questionnaire on behalf of Ahira H. Worden. We have:

- his name, race, sex, age and birth place/citizenship status from various sources (questions 1, 4–6, 10, 13–15)

- evidence of his Civil War service (2)

- his head of his household status (3)

- his marital status in 1859, with his wife still living (7–8)

- details reflecting he had at least one child (9)

- his parents’ places of birth from their marriage record, previous censuses, and newspaper articles (11–12)

Previous censuses also list Ahira as a farmer (16), and we don’t have any evidence of him being unemployed at the time (17). He wasn’t of school age in 1890 (18), and was able to read, write and speak English (19–21). From the 1880 census, we know he was not suffering any diseases or disabilities, nor was he a prisoner or convict (22–25).

We were also able to piece together information about the Worden household:

- Ahira owned the house outright (26), and we weren’t able to find evidence of a mortgage for either his home (27) or his farm (28 and 29)

- We admittedly don’t have an address for the family in 1890, but it’s reasonable to assume that Ahira and Elizabeth were in the same residence they occupied in the 1880 and 1900 censuses (30)

Instead of shying away from the 1890 census, we were able to find almost all the same details using other sources. By focusing on what we didn’t already know, we were able to consult the most relevant records and resources while employing the basics of genealogical research. So the next time you hit a supposed brick wall, remember: Don’t think “outside the box”—dig deeper into the information you already have instead. Happy digging!

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the September/October 2021 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: January 2025