Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

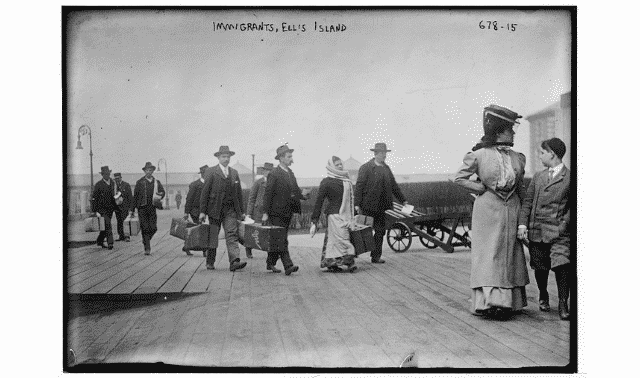

What is birthright citizenship, and how might it affect your genealogical research? Here are four quick facts.

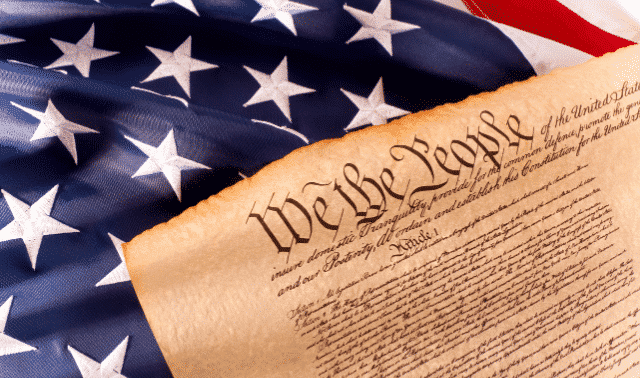

1. An 1868 Constitutional amendment allows for birthright citizenship.

The 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution, ratified in 1868 after the end of the Civil War, opens by saying:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside.

This sentence, now known as the Citizenship or Naturalization Clause, forms the legal basis for birthright citizenship.

ADVERTISEMENT

Subsequent Supreme Court cases and immigration laws clarified what circumstances the amendment covers. In United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898), the Court ruled that a child born to unnaturalized Chinese immigrants living in the United States gained US citizenship. The Naturalization Act of 1952 clarified the amendment also covers children born in US territories.

As a result, all children born in the United States—regardless of their parents’ citizenship statuses—automatically receive US citizenship.

2. Those born in the United States don’t need naturalization documents.

We’ve talked before about how useful naturalization documents can be. But if you know an ancestor was born in the United States after 1868, you won’t need to look for these records—even if you believe your ancestor’s parents never naturalized.

ADVERTISEMENT

If you’re researching an immigrant family, try to pin down where exactly your ancestor was born. Researching documents that mention your ancestor’s birthplace, such as death or marriage certificates and census records, might save you the hassle of looking for naturalization documents.

3. US birthright citizenship excludes certain individuals.

Namely, birthright citizenship does not cover children of foreign diplomats or of “hostile occupying forces” (e.g., the army of another sovereign state). Keep this in mind if you’re researching an ancestor who fits into one of those categories.

It’s unclear whether the government can legally, unilaterally restrict birthright citizenship further. Some argue the “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” clause allows officials to enact more restrictions, but legal scholars dispute this. Instead, they say only a constitutional amendment can change the text of the Constitution—and an amendment itself requires passage by supermajorities in both houses of Congress and ratification by three-fourths of US states.

4. The United States is one of many countries that grant birthright citizenship.

The United States, along with Argentina, Canada and several other North and South American countries, grants unconditional (or nearly unconditional) birthright citizenship based on the jus soli (Latin for “right of the soil”) principle. In addition, several other countries (including Australia, France and Germany) follow the jus soli principle if certain criteria are met. In the United Kingdom, for example, children born in UK territory receive birthright citizenship if at least one of their parents is a naturalized British citizen or has otherwise legally settled in the country. Keep these different sets of laws in mind as you research ancestors in other countries.

ADVERTISEMENT