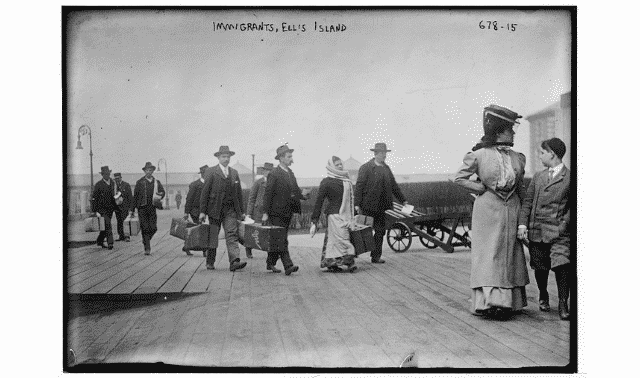

Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty welcomed the majority of the largely European tired, poor and huddled masses entering on the East Coast during the era of immigration. But most of America’s West Coast arrivals—Australians, New Zealanders, Canadians, Mexicans, Central and South Americans, Russians and especially Asians—were met with the harsh wooden buildings and fierce interrogations of Angel Island.

Opened a century ago, Angel Island (in San Francisco Bay) served a different role from its East Coast counterpart. Ellis Island was designed chiefly to process passengers and send them on their way. “Angel Island was really erected so people could be held there,” says Eddie Wong, executive director of Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation (AIISF). “A lot of people didn’t have a good experience.”

Immigrants often were detained for days or months before finally being granted entry in the United States—or forced to return to their home countries. Many of the detainees were so embarrassed about the experience or fearful of deportation that once they left the island, they also left behind their true history.

“A lot of people just don’t know about Angel Island,” says Judy Yung, a historian and co-author of Angel Island: Immigrant Gateway to America (Oxford University Press). “Those who came through, particularly Chinese, they didn’t want to remember. They didn’t want to share this with relatives.”

Did your ancestor arrive on the West Coast between 1910 and 1940? Do you suspect he or she was detained? That history isn’t lost. You can discover Angel Island’s past and your family’s story there—here’s how.

The History of Angel Island

Around the mid-19th century, America needed inexpensive labor to develop the Western frontier. At the same time, many young men in southern China’s Guangdong province wanted to find work opportunities abroad. To buy steamship tickets, they’d pull together all the funds they could muster from family or borrowed from US business agents against their future wages.

More than 123,000 Chinese immigrants, nearly all men, arrived on US shores between 1871 and 1880. Most found work in mines, on railroads and at low-end wage labor, intending to return home with their savings. But when the US economy took a downturn in the 1870s, many Americans laid blame for job scarcity on this visible minority. An anti-Chinese campaign led to a series of laws culminating in the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which put a 10-year moratorium on the immigration of Chinese laborers. Only merchants, clergy, diplomats, teachers and students were exempt from the ban. The law was renewed for another 10 years in 1892 and again, with no termination date, in 1902. Congress didn’t repeal it until 1943.

The 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire provided a way to work the system when it destroyed the city’s birth records. Chinese immigrants could claim they were born in the United States and request to bring family from China. They’d pad their number of children, use the necessary papers for their own families, and use or sell the extra “slots” to bring in relatives, other village residents, even strangers. These illegal immigrants were called “paper sons”; “paper daughters” were rarer.

Enforcing the immigration restrictions required a new facility—one that would prevent suspicious newcomers from communicating with those in San Francisco and isolate those with communicable diseases. Like the prison on nearby Alcatraz Island, the facility would have to be escape-proof. Despite the objections of Chinese community leaders, this hastily built immigration station was opened on the northeastern edge of Angel Island in January 1910.

Immigrants whose papers checked out disembarked in San Francisco. Others were ferried to Angel Island. There, they disrobed and were examined, measured with metal calipers and tested for disease. Those suspected of illegal entry were assigned a bunk in the detention dormitory to await interrogation by the Board of Special Inquiry, a government team of two immigrant inspectors, a stenographer and a translator. Detentions could last from a few days to several weeks; the longest was 22 months.

Officials, who’d quickly caught on to the “paper son” phenomenon, perfected a system of arduous interrogation that made it difficult even for legal immigrants to enter the country. Over the course of hours or days, immigrant applicants called before the Board of Special Inquiry had to recount minute details only a genuine applicant would know about his family history and his village. Most immigrants, determined to make a new life in America, prepared by studying coaching books containing hundreds of possible questions and answers. They spent months committing detailed responses to memory. Their witnesses—other family members detained at the station or living in the United States—were called to corroborate these answers. The slightest inconsistency could trigger prolonged interrogation and risk deportation for the applicant and his family.

Conditions at Angel Island were notoriously bad. The food, mostly stews of rice and vegetables, was barely edible. Public health officials deemed the buildings overcrowded, filthy, vermin-infested firetraps. Commissioner general of immigration Anthony Caminetti formally recommended removing the processing center to the mainland. Held under lock and key, many detainees poured out their frustration by carving poems into the wooden walls of the barracks. Below is a translated example that an unknown author scratched on the wall:

Imprisoned in the wooden building day after day, My freedom is withheld; how can I bear to talk about it? I look to see who is happy but they only sit quietly. I am anxious and depressed and cannot fall asleep. The days are long and bottle constantly empty; My sad mood even so is not dispelled. Nights are long and the pillow cold; who can pity my loneliness? After experiencing such loneliness and sorrow, why not just return home and learn to plow the fields?

After gaining admittance, many immigrants kept these details from even those closest to them. “They kept it a secret partly because they were humiliated by the treatment they got,” says Yung, whose parents were detained at Angel Island. “My dad was always afraid they would find him and he would be deported.”

Only around 1980, after Yung began work on her book Island: Poetry and History of Chinese Immigrants on Angel Island 1910–1940 (University of Washington Press), did her father begin to tell the truth about his history. To learn more about Angel Island history, view photographs, read barrack poems and listen to interviews with former detainees, visit AIISF online.

5 Steps to Finding Your Angel Island Ancestor

Now you can begin to shed some light on your own family’s Angel Island secrets. The majority of Angel Island immigrants weren’t detained, but if you think your ancestor was, look for an immigration case file investigating his claims.

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) branch location at San Francisco houses more than 200,000 such case files. Some are for Russians, Indians and Pakistanis, but most are for Asians—Chinese, Japanese, Koreans—because they were detained more often. The files are rich with information, including the person’s place and date of birth, a physical description, birth and marriage certificates, documents related to his other US arrivals and departures, interrogation transcripts, family photographs and maps immigrants drew of their home villages.

The National Archives has a variety of microfilmed records for the Port of San Francisco, including:

- Indexes to Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at San Francisco, 1893–1934

- Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at San Francisco, 1893–1953

- Registers of Chinese Laborers Arriving at San Francisco, 1882–1888

- Lists of Chinese Passengers Arriving at San Francisco, 1888–1914

- Lists of Chinese Applying for Admission to the United States through the Port of San Francisco, 1903–1947

For information on locating these microfilms, see NARA’s Immigrant and Passenger Arrivals catalog.

Follow these steps to retrace your ancestor’s paper trail.

Step 1: Determine the date and name

Establish when your relative may have arrived in the United States, and the name used at arrival. Talk to older relatives and gather any copies of old immigration documents such as certificates of identity, certificates of residence or steamship tickets. Search for the case file number using the free partial name index. This index contains more than 90,000 names with some vital information about the individual. It is also available on Ancestry.com.

Step 2: Find the case file number

If your ancestor isn’t in the partial name index, try to find him on a ship’s passenger list. Then you can deduce the number from the arrival year and the “ship number” on the day of arrival. Search passenger lists on subscription website Ancestry.com, which has an index to California passenger arrivals.

When you find the person, note the five-digit ship number written or stamped at the top of the page—this is the first part of the case file number. Then note the manifest page number and the line number (to the left of the person listed). This gives you the second part of the case file number. So, for Wah Lak, the person highlighted in this list, the case number is 14084/007-23.

Case file numbers were updated to reflect subsequent journeys to and from the United States. For example, if you know that your ancestor first immigrated to the United States in 1910, left to visit family in 1920 and came back for good in 1921, the case file number may have been changed accordingly. You would need to find the passenger list from 1921 and follow the above steps.

Step 3: Request files from the National Archives

Once you’ve found the case file number, you’ll want to either visit NARA in San Bruno or order copies of the records. For information on sending your request to NARA, contact the archives by e-mail or by calling (650) 238-3501.

Step 4: Search for other family members

If you can’t find a case file on your ancestor, try searching for another family member. Many case files include a page with file numbers for related cases, so your uncle’s file will likely reference your father’s file. If your ancestor had some action relating to his status as an alien resident or citizens after 1944, his immigration case files may have been placed into an Alien Case File, or A-File, in the custody of the US Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS). For information about how to request these files, visit the USCIS Genealogy Program.

Some who immigrated under false identities participated in the Chinese Amnesty Program, informally known as the Confession Program, to correct their status. These participants often subsequently changed their names to reflect their true identities. Case files of Angel Island immigrants who participated in the Chinese Amnesty Program also are in the USCIS A-Files.

Step 5: Research any lawsuits

If your ancestor filed a lawsuit related to the Chinese Exclusion Acts, those records may be at a NARA research facility. Ancestry.com has an index to these cases in its database US Chinese Immigration Case Files, 1883-1924. Use the information to request the full case file from NARA.

By taking these steps to research your hidden family history, you’ll both reveal the truth and honor the past.

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the August 2010 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: May 2025