Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Text by Sunny Jane Morton unless otherwise noted

Early Americans lived on the go. Even when families put down roots in one place, branches often wandered to neighboring states or across the country. Their moves made sense to them: away from failures or danger, or toward opportunities. But it can be maddening to track them. I often find myself singing my own version of the folk tune “Cotton Eye Joe” to my elusive ancestors: “Where did you come from? Where did you go? You were just in O-hi-o!”

Maybe your ancestors have you singing a sad song as you struggle to keep up with their peripatetic ways. How can you stay on their meandering trails? What do you do when they disappear from their hometown? How can you confirm someone is your ancestor and not another person by the same name? How do you construct a plausible explanation for their migrations?

It’s time to change your tune. Follow our research strategies to find your roving relatives, and soon you’ll be singing your own folk’s songs.

Why Your Ancestors Immigrated: Bound for the Promised Land

Our immigrant ancestors set the pace for generations of restless Americans to come. They crossed the sea, itself an uncertain journey. Some fled war, famine, poverty or persecution. Others answered beckoning relatives or came in hopes of work, land and a better future. Still others arrived unwillingly, in shackles.

Once here, many kept moving beyond teeming port cities. The enslaved endured forced marches as they were sold from place to place. For free folks, horizons were wider and more hopeful. They headed to industries growing up in remote places: Appalachian mountaintops, California streams, Texas stockyards. Cheap or free land lured settlers into the wide interior. When slavery ended, African Americans joined these mass migrations well into the 20th century: to prairie homestead land, Chicago meat-packing houses, Pittsburgh refineries, auto plants in Detroit.

When you start researching a family, you don’t always understand what (if any) “promised land” motivated their migrations. You don’t see the industrial barons’ advertisements that lured workers to mines, mills and factories. You may not know about irresistible land giveaways out West. So you have to ask yourself what compelled them to pick up and move to a new place.

Look for both “push” and “pull” factors. What events may have pushed them away from home? What pulled them to their destinations? The answers often relate to employment, loved ones and overall quality of life. Ask older relatives why family members moved. Look for clues to population movements in published local and family histories. Consult regional histories for the “bigger picture” of who was following the same migration pattern and why.

You can find compiled family histories and local history titles through the Library of Congress online catalog. Then find copies through WorldCat; borrow them through your local library’s interlibrary loan program. Or look for free, digitized versions on Internet Archive or Google Books or among more than 80,000 digitized local and family histories at FamilySearch (from the home page, click on Search, then Books). If you have African American roots, consult In Motion: The African American Migration Experience.

Tip: Learn the local history and geography. Local histories can document patterns that may explain the movement of groups of people that might have included your ancestors. Kearny, N.J., for example, drew large numbers of Irish and Scottish immigrants to work in its textile and linoleum industries. Similarly, silk mills in Paterson, N.J., attracted skilled workers from Poland. – Barbara Krasner-Khait

Migrating with Family and Friends: Come and Go with Me

Many Americans migrated with family members or friends. Try to account for every family member and known associate in every census. Watch for their marriage records, city directory entries, tax records, obituaries, grave markers and death records. Why track everyone? A group is more recognizable in records than a single person. If you lose your relative’s trail, you might pick it up again more confidently via traveling companions.

Here’s an example from my family. Henry Ellis married Henrietta Rowell in Ohio in 1844, then moved to Iowa, where Henry’s brother Woodin lived with them. Henry doesn’t appear in the Iowa census in 1880, but a Henry Ellis shows up in the Polk County, Ore., census. At first I assumed that wasn’t my Henry. Then I found Woodin Ellis in the 1880 Polk County census and a local divorce record for Henry Ellis and Henrietta Rowell. Finally I discovered grave markers for Henry and Woodin Ellis in the same Polk County cemetery. This bigger picture gave me more confidence that I’d found “my” Henry.

In another case, a daughter’s migration was key to understanding her father’s otherwise mysterious move. Andrew O’Hotnicky had lived his entire life in the same small Pennsylvania neighborhood. But the only burial record I could find was miles away in Harrisburg. Harrisburg city directories listed him there just before his death. It didn’t make sense until I found his daughters living in Harrisburg. A distant relative confirmed that the father moved there to be with his grandchildren.

Online indexes are the easiest place to widen your census research net. Try different searches for elusive ancestors: After searching on a full name, use initials or just a middle name. Wildcard characters are useful in databases that allow it. Usually, an asterisk stands for any number of letters (for example, Tho* will find Thompson and Thomas) and a ? substitutes for one letter. Browse records for the place your ancestors lived to search for badly indexed names. Where possible, search census indexes on multiple websites, as each may have indexed a name differently.

Look for US censuses on the free websites FamilySearch and HeritageQuest Online (available through many local libraries), or by subscription at Ancestry.com, Archives, Findmypast and MyHeritage. For city directories, check libraries and Ancestry.com. Keep track of web searches with our free Online Search Tracker (click on Research Trackers and Organizers).

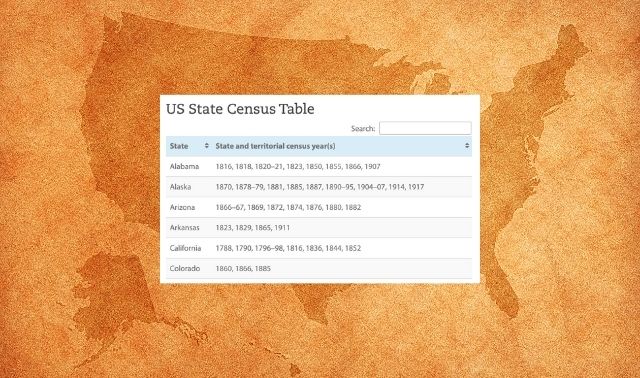

Tip: City and rural directories and state censuses can help you track an ancestor’s whereabouts between US censuses.

Tip: Pay attention to names. Many families traveled with their neighbors and relatives. They may have started out together or come together by marriage en route. Document the names of witnesses on records and recipient names of personal correspondence. – Barbara Krasner-Khait

Looking for Work: I Owe My Soul to the Company Store

Just as we do in today’s world, our ancestors followed paychecks. A new opportunity can easily explain an otherwise mysterious migration. Investigate your ancestor’s employment as well as the job markets in both his new home and the one he left behind.

First, try to determine what kind of work an ancestor did. Family memory and passed-down papers or artifacts may have the answer. You also might find an ancestor’s occupation or an employer’s name in census entries, military service records, draft registrations, city directories, passenger lists, naturalization documents, death certificates and obituaries.

Some people didn’t practice a consistent trade. Skilled immigrants often left their professions if they didn’t speak English or faced discriminatory hiring. Also, some career paths wandered or evolved. One of my ancestors went from farmer to grist mill owner to merchant; another, from justice of the peace to attorney to judge. Collect as many career details as you can from the genealogical records you’ve already found. You may identify a person more easily in records of an unexpected locale if he’s doing a similar type of work, as my attorney ancestor did.

Next, consult regional histories and records. In the old hometown, look for reports of factory or mine closings, layoffs, strikes, riots, natural disasters or accidents. Check county histories of the new hometown for reports of thriving industries (these may be buried in biographical sketches of prominent businessmen). Watch for mention of roads, canals and rails coming to town, which often spurred economic and population growth. Consider the possibility that an incoming ancestor worked on that new infrastructure.

Regional industrial histories may cover the local booms and busts of mining, refineries, mills, factories and more. You might learn about efforts to recruit workers, living and working conditions; and the fates of displaced workers may have gone next. Find industrial histories listed in WorldCat and on shelves at major libraries. Local historical societies also may carry or suggest titles.

Tip: Find written accounts. Journals and letters may have described the migration experience, means of travel, the places they saw and the people they met or traveled with. Maybe your family has such sources. If not, look for written accounts by others whose migrations parallel those of your ancestors. Books such as Lillian Schlissel’s Women’s Diaries of the Westward Journey (Schocken Books) or Kenneth Holmes’ Covered Wagon Women: Diaries and Letters from the Western Trails, 1840-1849 (University of Nebraska Press) provide excellent examples. – Barbara Krasner-Khait

Real Estate Opportunities: Home on the Range

Many of our ancestors migrated in search of a home on the range (or in the rolling hills, or along the river). Never mind watching the deer and antelope play: Your family may have viewed land ownership as a way out of persistent poverty. Back in the Old Country and eventually in the eastern United States, land that could support a family was taken, expensive or overworked.

Searching for property ownership, especially government-granted, may take some time. Look for hints in records you already have. Federal censuses of 1850, 1860 and 1870 have a column for the value of real estate owned. Beginning in 1900, a census column indicates whether the family owned or rented its home. Tax records should specify whether a family paid taxes on “real property” (meaning real estate), and may even give the acreage. Probate documents will mention land in an estate, though sometimes a landowner passed it on to heirs before dying.

If your ancestor was an early settler in an area, it’s possible he or she received an original land grant from the state or federal government. Turn to genealogical guides such as our State Research Guide series or The Family Tree Sourcebook for more information on finding land grant records in each state. You can search most federal land patents issued by the Bureau of Land Management’s General Land Office on its website.

The land patent will state whether the land was bounty land—a reward for military service from the Revolutionary War through the Mexican War (although the veteran or his heirs often sold their land). Look for bounty land warrants at the National Archives or on subscription site Fold3. Awarded patents are indexed at FamilySearch and Ancestry.com. State archives may have their own bounty land paperwork.

Property acquired after the original government land grant should be recorded in county deed books. Few deed books are digitized online; you’ll probably need to research them in person at the county recorder’s or deed office. If you’re lucky, though, indexes and/or deeds may be on microfilm—search by county in the FamilySearch online catalog. Indexes will lead you to original deed records, mortgages and related documents.

Remember that just because an ancestor owned property doesn’t mean he stayed put forever after. Many settlers improved a piece of land for a few years, then left. Especially in the vast Western prairies, weather would make or break a farm. Failed homesteaders may have relocated to a former hometown; to big cities such as St. Louis, Denver or Portland; or to mines or refineries where work was a sure (if not permanent) thing.

Tip: Use land records to help you sort out same-named men in a town. Two men wouldn’t own the same piece of land at the same time.

Tip: Identify boundary line changes in counties and states. Map aids such as the US Geological Survey’s Geographic Names Information System can help you find place names used on USGS topographical maps, including some family cemeteries and schools. – Barbara Krasner-Khait

Following Interstate Transportation: 15 Miles on the Erie Canal

How our ancestors reached their destinations is an important part of the migrants’ story. Remember Henry Ellis’ move from Iowa to Oregon? As it turns out, Polk County lay at the end of the Oregon Trail in the Willamette Valley. It would’ve been a difficult overland journey for older men like Henry and Wooden Ellis. Their arrival not long after rail service reached Polk County is probably not a coincidence.

Would your ancestors have wandered by water, trail or rail? Keep the following transportation facts in mind.

- Waterways were the easiest way to travel before railroads. Boat passage was less expensive and easier on the joints, and travelers could carry more luggage. The Ohio River served thousands of travelers from Pennsylvania and points east beginning in the late 1700s. That river dumped into the Mississippi, which carried folks south to New Orleans, north to Minneapolis and everywhere in between. Canals had their heyday (especially in New York, Pennsylvania and Ohio) from the 1820s to the railroad era.

- Overland trails and roads often linked major cities with each other and with waterways. Over time, side roads led off the major thoroughfares. One of my relatives bought land in an inland Ohio county in the 1830s. That decision didn’t make sense until I learned that the National Road was built through that county a few years earlier.

- Railroads began linking eastern states in the 1840s. By 1860, rail service connected all states east of the Mississippi. The first transcontinental railroad with service to Sacramento was completed in 1869, with four transcontinental tracks in place by 1885 (two to Los Angeles and one to Oregon). Thereafter, branch lines filled in the gaps to other destinations.

Use historical maps to locate navigable waterways, roads, rails and canals in use during specific times. Over 38,000 historical maps are in the David Rumsey Map Collection, which you also can view at the Digital Public Library of America. Find maps of the famous Erie Canal. The Library of Congress has a special category for railroad maps in its Maps section. A series of detailed atlases and gazetteers by Carrie Eldridge charts migration routes from New England and the South across the Appalachians and into the far West. Additional migration resources (trail maps, timelines and histories) are accessible at this archived webpage from Genwriters.

William Dollarhide, in his book Map Guide to American Migration Routes, 1735-1815 (Heritage Quest), advises, “Get a good [current] map and trace the old migration routes with the modern highways of today. Find the counties that the routes pass through, and make a list of the places where an ancestor may have stopped en route to a final destination.”

Researching rail service? Local histories often mention the arrival of the railroad in their county or town. Find a railroad history collection at the University of Connecticut library. Another solid resource for railroad research is the related category page on Cyndi’s List.

Tip: Study the transportation corridor itself. Choose a trail or road or railway with special significance to your heritage and seek information from many sources—books, periodicals, videos, television documentaries and the internet, as well as local historical societies, museums and libraries along the route. – Barbara Krasner-Khait

Sorting Out Identity: Oh My Darlin’

You’re likely more faithful to your ancestors than the fickle fellow of this famous ‘49ers song was to his love: “How I missed my Clementine! But I kissed her little sister, I forgot my Clementine.” In the absence of his beloved, he turned to another of the same surname. How do you avoid settling on another when you’ve lost track of your own?

Gather as much data as you can—quality information created as close to the time of the event as possible by independent sources (not online family trees that copy each other). When I was trying to decide whether the Henry Ellis in Iowa was the same guy as the Henry Ellis in Oregon, I gathered and compared data for the men both locations. I made sure birth dates and other details were fairly consistent, allowing for errors in reporting or recording. I found a plausible reason for this farmer to go to the Northwest: fertile land. I noted the newly arrived rail service. Finally, I confirmed that no overlapping records existed: My Henry Ellis disappeared from Iowa records about the same time the Oregon man appeared.

Sometimes you’ll find a “red herring:” another person with your ancestor’s name living in the same place. This happened when I was trying to learn whether my merchant ancestor Thomas Selby hopped a ship for California during the Gold Rush. A Thomas H. Selby—a successful businessman of about the right age—appears in many San Francisco records. Too many, as it turns out. Thomas H. Selby founded the Selby Smelting Works, became the mayor of San Francisco and died there in 1875. By 1859, my Thomas Selby was homesteading in Missouri with his family. Not the same person.

Sorting out identity isn’t always that easy. My husband’s great-grandfather Charles Clay Morton lived in the same West Virginia locale as another Charles Morton of about the same age. As it turns out, Charles Clay consistently used his middle name in records. But I couldn’t confirm that without carefully comparing all records relating to both men, from their signatures to physical descriptions to spouses’ and parents’ names.

Tip: Create your own map. Show the junctions of families through marriage along with their places of origin and their subsequent moves. Your own “map” may be a simple chart on paper, a tracing-paper overlay on a printed map, or a slick creation using one of the many mapping-software programs. – Barbara Krasner-Khait

Confirming Place of Death: St. Peter, Don’t You Call Me

At some point, every ancestor’s trail ends. Death records may be sparse in frontier areas, especially where the bulk of the population was made up of transient workers doing dangerous jobs. Look for these folks in cemetery records and tombstone inscriptions, newspaper obituaries and government reports of industrial accidents. Migrant women may have died in childbirth, but they may also have “disappeared” if they married or remarried and took a different surname. Look for evidence of any such marriages before proclaiming them dead.

Next, move backward along that person’s migration trail for evidence that he retreated “back home” to die. Track down younger relatives and in-laws: A census entry might show your older relative living with them. Look for a death date in family letters, Bibles and other documents or memorabilia. Broaden online searches for your relative—living or dead—to statewide or nationwide parameters, and watch for details that look familiar.

In the absence of death data for a person, you may need to construct one last plausible scenario. Search local histories or newspapers for possible causes of death, such as epidemics and natural disasters. Then summarize all the places you’ve looked. If the trail ends with no death record, make a note in your records, so you’ll remember that loose end in the future.

At this point, it may be time to whistle a new tune as you turn your attention to a different wandering ancestor. Maybe you’ll find inspiration of your own as you lay down a soundtrack for another relative’s life.

Tip: Create a timeline. Who was where when? To keep track, document your family’s movement, indicating significant events by date and location. Incorporate any local history details into your timeline that may explain migrations. – Barbara Krasner-Khait

Timeline

Highlights of American history, comprising important infrastructure improvements and impetus for migration across the country

1755 Braddock Road crosses the Appalachian Mountains

1796 Kentucky legislature opens the improved Wilderness Road to wagons

1797 Zane’s Trace is completed from Wheeling, Va., to Maysville, Ky.

1801 US Army starts blazing the Natchez Trace from Natchez, Miss., to Nashville, Tenn.

1818 National Road reaches Wheeling from Cumberland, Md.

1820 Congress authorizes extension of the National Road to St. Louis

1825 Erie Canal completes a navigable water route from the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes

1827 Baltimore & Ohio railway opens from Baltimore to Ellicott’s Mills, Md.

1848 Gold discovery at Sutter’s Mill kicks off the California Gold Rush

1862 Abraham Lincoln signs Homestead Act of 1862

1869 First Transcontinental Railway dedicated at Promontory Summit, Utah Territory

1889 50,000 line up for first Oklahoma land run into Unassigned Lands

1910 Great Migration of African Americans begins to Northern and Midwestern cities

1913 Cross-country Lincoln Highway is dedicated

1916 Federal Aid Road Act matches state funds for road improvement

1930 Severe drought begins in the Great Plains, eventually displacing 2.5 million

Related Reads

Versions of this article appeared in the October/November 2013 and April 2001 issues of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated April 2025.

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for site to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to affiliated websites.