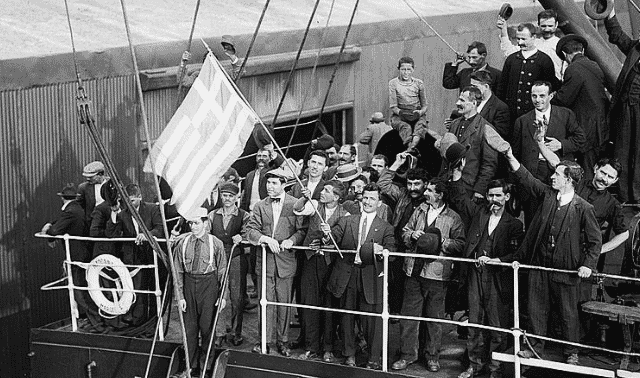

Our immigrant and ethnic ancestors made American history. Their names may not appear in the history books, but they were there: the American Indians who solely inhabited the North American continent until the Spanish and English arrived; the Africans who were brought against their wills to plant and harvest the fields; the Germans and Irish and Italians and Poles and Chinese and others who helped build the cities, lay the railroad tracks and cultivate the farmlands. Do you know which of these nameless people in American history are your ancestors?

Everyone has immigrant ancestors. Whether your ancestors arrived in the 1900s, the 1600s or were here to greet the rest, all American ancestry leads somewhere else. Some archeologists have said that the North American continent has been inhabited only recently compared with other continents—when Asian migrants crossed the ancient “land bridge” of the Bering Strait. While descendants of these early “immigrants” have no written contemporary records to aid in tracing their ancestry, their forebears did leave physical evidence in the form of artifacts. For those whose ancestors arrived in America since the 1600s, a multitude of sources can help research those immigrant origins. And if you have American Indian ancestry, you’ll find a surprising amount of information about numerous tribes since the “founding” of our nation.

Everyone has ethnic ancestors. Maybe you descend from several different ethnic forebears. An ethnic group is one that has a socially distinct cultural heritage. This is what makes Italians Italian, Poles Polish, Chinese Chinese and Mexicans Mexican. To keep ethnic identities alive, these cultural features are handed down from one generation to the next. But not everyone cares enough to research the cultural differences that originated with their immigrant ancestors and to insure that those customs and traditions survive. As sociologists point out, ethnic differences are culturally learned, not genetically inherited.

Tracing your immigrant, ethnic heritage is an exciting journey. Many people who begin researching their family history do so to discover who their immigrant ancestors were—the first in their family line to come to America. Many of us feel a need to know who we are and where we came from beyond America’s shores. Researching your ethnic ancestors will not only fill that need, but also give you a sense of your ethnic heritage—an invaluable inheritance to pass on to your children and grandchildren. Here are 10 steps to get you started.

Step 1: Start with Your Immediate Family

Everyone starts at the same place, no matter what your ethnic heritage. Start with yourself and work backward in time. Record what you know about you, your parents and your grandparents on charts and forms that you can download free, or you can enter your data into a genealogical software program.

Step 2: Gather Stories

Oral history can offer important clues to your immigrant and ethnic ancestors. Ask your relatives specific questions about your family’s arrival in America. Record all stories as they’re told to you, regardless of the accuracy. You may hear the story that your ancestor came over as a stowaway, or that there were three brothers who initially came, or that you descend from a Cherokee Indian princess. These are common family legends and often are glorified versions of the actual story. With further research you’ll be able to determine if the story is just a tall tale or an accurate account.

Here are some key items you’ll want to ask about as you talk with relatives about your ethnic and immigrant ancestors:

- places where the family settled in America (including ethnic neighbors) and subsequent residences and dates

- name changes and original names

- date of arrival in America

- names of ships

- ports of departure and arrival

- name of village, province or country where immigrant ancestor originated

- whether the ancestor ever returned to the native land and, if so, when

- religious affiliations, special feast or saints’ days celebrated

- memberships in ethnic organizations

- occupations

- military service in America and the homeland

- ethnic recipes handed down in the family

- favorite music, dances

- marriage customs

- naming practices

- funeral customs

- attitudes toward education

- attitudes/prejudices toward other ethnic groups

- prejudices felt or experienced from other ethnic groups

If you have Native American Indian ancestry, take note of the name of the tribe, whether the individual was living on a reservation and when, the Indian and English names, and any migratory (voluntary or involuntary) patterns. If you have stories of American Indian ancestry and haven’t been able to identify the tribe, ask what language ancestors spoke, what religious beliefs and ceremonies they celebrated, and what the familial ties were. Then match these with published accounts such as those in encyclopedias of American Indian tribes.

Also take note of where ancestral family members lived at different times, since this will be important in locating records. Remember, however, that one of the most common family stories passed from one generation to the next is that of American Indian ancestry. You need to investigate whether this story is true.

If you have African-American ancestry and your ancestors were slaves, try to learn through oral history interviews the names of the slave owners. Surviving plantation records and other documents generated by the slave-owning family will be key in your search.

Step 3: Do Your US Homework

Exhaust all American sources before attempting to research in another country. No one wants to trace the wrong ancestors. By doing your homework, you’ll be assured that you’ve got the right family once you get into foreign records.

Read a basic genealogical guide that will help you find and use common genealogical records, such as vital records, censuses, land records, wills and so forth. You can find basic guidebooks at your local bookstore or on Amazon.

Step 4: Tackle Specialized Records

Next, look for American records specific to ethnic and immigrant groups. African-American researchers will look at specialized records such as slave schedules, plantation records, records of the Freedmen’s Bureau and signature cards for the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company, to name a few. You can learn about these records by consulting a guidebook for researching black ancestral roots, such as Dee Parmer Woodtor’s Finding a Place Called Home: A Guide to African-American Genealogy and Historical Identity (Random House) or David T. Thackery’s Tracking Your African American Family History (Ancestry).

American Indian researchers will look at specialized records such as Indian census schedules and other federal records created in the relocation of tribes. These records and others are described in Curt B. Witcher and George J. Nixon’s chapter, “Tracking Native American Family History,” in The Source: A Guidebook of American Genealogy, edited by Loretto Dennis Szucs and Sandra Hargreaves Luebking (Ancestry).

For those whose ancestors immigrated to America, naturalization records and passenger arrival lists are a key resource.

Naturalization records

Depending on the time of your ancestor’s arrival, naturalization records can give you the precise date and port of arrival, as well as the name of the ship, the port of departure and the immigrant’s date and place of birth. Some records, however, may give you only a year when the immigrant arrived.

Between 1776 and 1790, each state established laws, procedures and residency requirements for aliens to become naturalized citizens. Since 1790, when the first federal naturalization law was passed, a series of acts have changed restrictions and requirements over the centuries. For more detailed coverage on naturalization laws and records, see American Naturalization Records, 1790-1990: What They Are and How to Use Them by John J. Newman (Heritage Quest) and They Became Americans: Finding Naturalization Records and Ethnic Origins by Loretto Dennis Szucs (Ancestry).

Before 1906, an immigrant could go to any court of record and apply for citizenship. In fact, your ancestor could have initiated naturalization in one court and completed it in another court. The Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization—now known as the Citizenship and Immigration Services—was established in 1906, and copies of all naturalizations made after this date in courts around the country were forwarded to that agency. Becoming a naturalized citizen was standardized and involved the process of filing a declaration of intention (“first papers”), then, after fulfilling the residency requirement, filing a petition for naturalization, which required the applicant’s signature (“second papers” or “final papers”).

To obtain naturalization records, check at courthouses—municipal, county, state and federal—where the immigrant arrived and/or settled. These records as well as indexes to the records may have also been microfilmed by the Family History Library in Salt Lake City and digitized on FamilySearch. Also check city, county and state archives.

Naturalizations made in municipal courts may be found in the town halls or city archives of some major cities, such as Baltimore, Chicago and St. Louis. If these avenues fail, write to the USCIS. Look into how to make a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request.

As you’ll learn from reading social histories (see Step 5), members of some ethnic groups were slow to become naturalized, if at all, or were not allowed to do so.

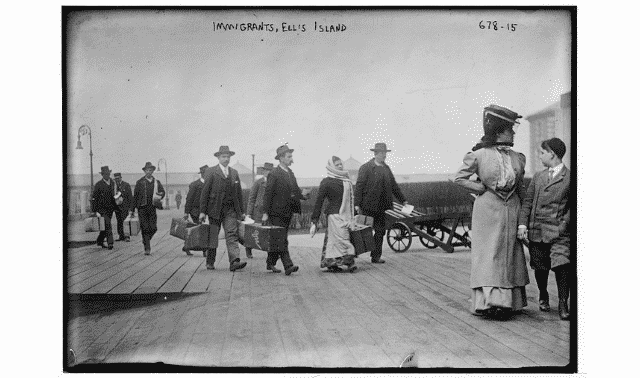

Passenger arrival lists

The federal government didn’t begin keeping a record of immigrant passenger arrivals until 1820, but many pre-1820 passenger lists created by state or local authorities have been published in a multitude of works. P. William Filby and his co-editors provide indexes to some of the passenger arrival information available in a multi-volume reference guide, Passenger and Immigration Lists Index: A Guide to Published Arrival Records of about 500,000 Passengers who Came to the United States and Canada in the 17th, 18th and 19th Centuries, available in libraries. First published in 1981, the guide has several supplements and covers more than 3 million people. The information in these volumes comes from published sources, not original records. Keep in mind that the date associated with an ancestor’s name may not be the date of arrival, but the date an ancestor was first mentioned in a record as being in America.

Most original passenger arrival lists from 1820 to 1957 (with some gaps) have been microfilmed and are available through the National Archives, FamilySearch and sites like Ancestry.com.

The information you can glean from these records varies. Passenger lists from 1820 to about 1891 were known as Customs Lists. They were usually printed in the United States, completed by ship company personnel at the port of departure, and maintained primarily for statistical purposes. So their data is scanty: name of the ship and its master, port of embarkation, date and port of arrival, each passenger’s name, sex, age, occupation and nationality.

Arrival records created from about 1891 to the 1950s are referred to as Immigration Passenger Lists. Like Customs Lists, these were printed in the United States, but completed at the port of departure, then filed in the United States after the ship docked. The information provided in Immigration Passenger Lists varied over the decades. As the influx of immigrants became greater, more details were recorded. For example, in 1893, there were 21 columns of information; in 1906, 28; in 1907, 29; and in 1917, 33. All of these details are valuable to your research, but in particular, you can get clues you may not find anywhere else from items such as last residence; final destination in the United States; if going to join a relative, the relative’s name and address; personal description; place of birth; and name and address of closest living relative in the native country.

You can also tap the Immigrant Ships Transcribers Guild, which currently has a database of nearly 20,000 passenger lists from all time periods and from several ports.

Step 5: Study Social History

For more clues, study your immigrant or ethnic group’s social history. Social histories look at the lives of ordinary people in everyday society. From these books, you will learn about the customs, culture and folkways of your ancestor’s group while in America. This information might lead you to other sources, will help explain your ancestor’s behaviors, and will give you an appreciation for your ancestor’s life.

While there are social histories written about most ethnic/immigrant groups, good starting places are Coming to America: A History of Immigration and Ethnicity in American Life by Roger Daniels (Harper-Perennial) and Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups edited by Stephen Themstrom, Ann Orlov and Oscar Handlin (Belknap Press). For specific social histories, look in your library’s catalog under the ethnic group, then the keywords social life and customs.

Step 6: Join an Immigrant or Ethnic Genealogical Group

By networking with others who are also interested in researching your heritage, you’ll learn about all sorts of sources and strategies to help you in your own search. Almost every ethnic group has a corresponding genealogical society. Consult The Genealogist’s Address Book, 4th edition, by Elizabeth Petty Bentley (Genealogical Publishing Co.) or visit Cyndi’s List. Look under your ethnic group in either of these sources, and you’ll find a wealth of resources.

Ethnic genealogical societies have members from all over the country and sometimes from the foreign country where ancestors originated. Typically, the society produces some kind of periodical, either a newsletter or a journal. Members and professional genealogists write articles offering advice on researching the ethnic group in America and in the homeland. You’ll also find advertisements for translating services and professional genealogists who’ll do research for you, either in America or abroad.

Also check with your local library or genealogical society. Many local genealogical organizations have special-interest groups that focus on an ethnic group, such as Germans from Russia, Palatines to America, African-Americans or Jewish immigrants. These offshoots typically meet apart from the general genealogical society.

Step 7: Read Genealogical Guidebooks Specific to the Immigrant or Ethnic Group

Almost every group has a research guide to help you learn about records in foreign countries and how to access them. Family Tree Magazine features a different ethnic group in most issues. The FamilySearch Wiki includes foreign source guides and research outlines for many common ancestries.

Genealogical publishers offer many different ethnic guidebooks such as, A Genealogist’s Guide to Discovering Your English Ancestors by Paul Milner and Linda Jonas, A Genealogist’s Guide to Discovering Your Germanic Ancestors by S. Chris Anderson and Ernest Thode, and A Genealogist’s Guide to Discovering Your Italian Ancestors by Lynn Nelson.

Step 8: Tap Foreign Records from the United States

Often it’s quicker, easier and cheaper to do foreign research right here in America. For example, the US-based Family History Library has digitized its millions of its rolls of microfilmed records. While it doesn’t have every record from every part of the world, you might be surprised to find records of your ancestor’s remote village just waiting for you to look at them.

Remember, unless you’re researching in an English-speaking country, the records you find will be in the language of that country. For Catholic church records, they may be written in Latin, regardless of the spoken language. Arm yourself with a good foreign language-English dictionary, and take advantage of the huge list of online dictionaries at YourDictionary.com. Many of the genealogical guidebooks on foreign research will give foreign word lists and translations of common words, as will guides from FamilySearch and many ethnic-genealogy websites.

Step 9: Research Records in Your Ancestor’s Homeland

For researching records that aren’t available online, ones that you can access only in the foreign country, you have three options: you can write to the record repository and request the records directly; you can hire a professional genealogist who will do on-site research for you; or you can make a trip to your ancestor’s homeland yourself to do research.

When writing to a foreign record repository, write the letter in the language of the country. Many of the genealogical guidebooks and websites on foreign research will provide you with form letters. Ask for only one or two items at a time, and see what kind of response you get before asking for more. Include with your inquiry two postal International Reply Coupons, which you can purchase at your local post office. (There’s no need to send a return envelope.) If you need to send money, try sending a postal money order or go to your bank and get a money order in the currency of the country. The guidebooks should tell you about how much you need to send.

If you want to hire someone, first check with the Association of Professional Genealogists in America. Look under the country or ethnic group of interest for a researcher who specializes in this heritage. Even if this person specializes in the ethnic group in America, he or she may be able to refer you to a genealogist in the foreign country.

Finally, if you’re planning a research trip to your ancestral home, make sure you’ve done all your homework before you leave. That is, make sure you’ve done steps 1 -8 above. You certainly don’t want to waste time looking at records you could have looked at in America or be unfamiliar with the repositories that house the records in the country you’ll be visiting. If you’ve joined an ethnic genealogical society, network with others who’ve been to the country where you plan to visit and do research; they can be the best resource for giving you research and travel tips.

Step 10: Share Your Findings

Don’t forget to write your immigrant or ethnic ancestors’ stories and share what you’ve learned about your heritage. Writing your ancestors’ stories leaves a legacy. You, the family historian, have the responsibility not only to learn about your ancestors through research, but also to pass that information along to future generations.

This means doing more than merely filling out a pedigree form. On a chart, your ancestors are just names. In a narrative, they become people. You’ve gone through all the time, expense and trouble to get to know your ancestors, to appreciate what it took for them to leave behind loved ones and their country, to settle in a strange land, either willingly or unwillingly. What a terrible waste and injustice it would be to leave them just as names on a chart! Share the stories, customs and traditions of your immigrant and ethnic ancestors. They deserve to be remembered. They are, after all, American history.

A version of this article appeared in the December 2000 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated, January 2022.