Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

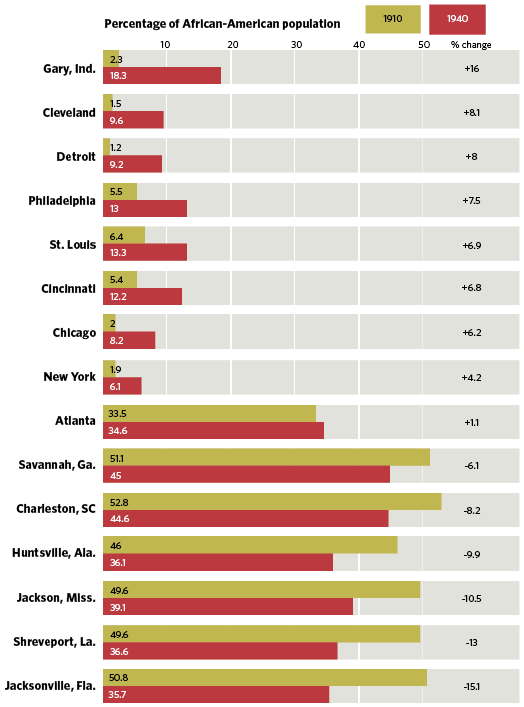

When it comes to researching African American family history, the obstacle of finding enslaved ancestors looms largest in family trees. But another, 20th-century challenge faces many genealogists: finding African-Americans who left the South about 47 years after slaves were freed, during the Great Migration of the 20th century. This huge population shift saw 1.6 million Black people move from the rural South to the urban North between 1910 and 1930. (Some historians differentiate between this era and a second Great Migration that took place from 1940 to 1970. We’ll focus on the earlier time span.)

You might encounter this problem as you follow traditional genealogical principles, researching from yourself backward, and suddenly can’t find your grandparents or great-grandparents in their Northern hometown. How do you research these people on the move? It’s simple: Think like an immigration researcher—that is, apply research methods used to trace immigrants from overseas.

Plenty of resources can help you piece together the migration path of your African American family: the US census; birth, marriage and death certificates; city directories; military records; newspapers; and slave narratives. We’ll show you how to use these sources to piece together your family’s past in their places of origin—and where they landed.

Why Did the Great Migration Occur?

Like many European immigrants, African Americans migrated for economic reasons. In the South, a boll weevil infestation reached southeastern Alabama in 1909 and spread to all US cotton-growing regions by the mid-1920s, severely reducing the demand for Black farm workers. Northern employment agents recruited African Americans and paid their travel expenses. In Northern states, they found better-paying jobs in factories during the labor shortage created as soldiers departed for World War I. The new arrivals worked for tanneries, steel mills and railroad companies.

Black newspapers such as the Chicago Defender helped persuade many to leave the South. The Defender was filled with train schedules and employment listings. Other papers, such as the Pittsburgh Courier and the New York Amsterdam News, reported that the North provided better education for children, higher-paying jobs, more-secure voting rights, and access to improved housing.

Most early Great Migration migrants went to New York, Pittsburgh, Detroit and especially Chicago. The Windy City’s Black population, which was only 2 percent in 1890, doubled to 100,000 by World War I, according to the Newberry Library. By 1970, one-third of Chicago’s population was African American.

Later, during the 1940s and World War II, migrants from the South moved to Los Angeles; San Francisco; Oakland, Calif.; Seattle; and Portland, Ore.

Black people also left the South to escape the Jim Crow system of racial segregation. The 1896 US Supreme Court ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson allowed “separate but equal” public facilities such as transportation, water fountains, schools and restrooms. African Americans had to sit in designated “colored” sections on trains, drink from colored water fountains, use colored bathrooms and attend segregated schools. By 1908, 10 Southern states had rewritten their constitutions to create literacy tests, poll taxes and grandfather clauses that blocked Black men from voting. The Ku Klux Klan, outlawed in 1871, re-formed in 1915 in Atlanta. Southern Blacks faced intimidation and deadly violence: A 2015 report from the Equal Justice Initiative documented 3,959 lynching deaths in 12 Southern states between 1877 and 1950.

Tip: Learn more about the Great Migration from the Library of Congress’ African–American Mosaic exhibit and In Motion: The African-American Migration Experience.

Start with the Census

Focus on discovering exactly where your relatives lived in the “old country” down South, the towns and states where they lived, and when they lived there. As you do, record their full names, nicknames, locations (county and state) and years lived there, and birth, marriage and death dates.

Next, find your kinfolk in the 1940 US census, taken as the Great Migration was underway. They may be living in the North by then. You can search this census online and view pages free at FamilySearch.org, or with a subscription to Ancestry.com. This census has clues to the place they migrated from: Check the Place of Birth column as well as the one for “Residence, April 1, 1935.” This lets you confirm the city, town or village, county and state where the family lived five years earlier. If it’s different from their home in 1940, and it’s in the South, you might have pinpointed their hometown or an interim location.

Once you find your family in the census, take note of the nearby households—neighbors and possibly friends. Just as European immigrants did, many African Americans migrated in groups or moved to the same Northern town. If you can’t find your family in other censuses, finding the friend’s listing might reveal your relatives living nearby.

Continue to search for your family back every 10 years in the census, checking each one for your family’s location until you find them down South. Remember that household members will be 10 years younger in each prior census (give or take—people weren’t always consistent in giving their ages) and at some point will be a child in the household of parents or other adults. You’ll have simultaneously traced their migration to the North in reverse.

Find Vital Records

Let your census finds be a springboard into other records. North Carolina native Sarah Enoch, daughter of Bedford and Tena Enoch, was born in 1866. She married George Walker, Jr. when she was 15 and he was 29. They were the parents of Bertha, Minnie Viola, and Bedford. There’s no known record of what happened to the marriage—whether it ended in divorce or George’s death.

Sarah, on the other hand, remarried, in Alamance County, NC, in 1899. By 1910, she and her new husband, Isaac Walker, had moved to Greene County, Ohio. According to the 1910 census, they lived with their son Johnny, Sarah’s son Bedford, and her mother, Tena. That census yields other facts and clues that can be confirmed in birth, marriage and death records: Isaac and Sarah had been married for 10 years, Sarah’s marriage to Isaac was her second marriage, and they had a son named Johnny. Sarah had borne seven children and four were living; the youngest, 10-year-old Johnny, was born in North Carolina. That provides a time frame for the family’s move to Ohio.

Next, locate all available birth, marriage and death records for the family, starting where the family settled in the North. States and counties kept these records generally beginning in the early 1900s, though some areas may have started keeping them earlier or later (see statewide record-keeping dates in our Vital Records Chart).

Look first for a person’s death record, which in the 20th century probably provides his parents’ names and birthplace. This is a valuable lead to the maiden name of a formerly enslaved woman, an especially difficult relative to trace. Death and marriage records may be restricted for 25 or 50 years after the person’s death, though you may be able to access an index and/or order a copy of the certificate if you can prove you’re a descendant. Birth records are often restricted for 75 to 100 years.

Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.org have birth and death indexes and records for many states. To find records, run a Places search of the FamilySearch online catalog and look under the vital records heading. Use a link in the record’s catalog listing to see if it is available digitally on FamilySearch or at a local Family History Center. You also can contact the county or state vital records office where the event occurred to request copies (usually for a fee).

Remember that, because informants provide details about the deceased and his parents, some information on death certificates is considered secondary information. You’re relying on the informant’s knowledge and memory, so the information provided may be inaccurate or you might discover a blank line.

A search of county records in Ohio and North Carolina and found Isaac and Sarah’s marriage certificate in Alamance County; the marriage and death certificates for Bedford, Minnie and Bertha; and Tena’s death certificate in Ohio. Plotting all the dates and places on a timeline reveals points along the path of the family’s migration.

Check City Directories

The city directory, which is like a phone book without the telephone numbers, is an effective way to trace family members as they migrated north, especially if they left during those 10 long years between federal censuses. City directories (which also might cover the surrounding rural area) list the names of employed adults in a household with their addresses and occupations. A wife’s name might be listed in parentheses after her husband’s. You also might find death dates for those who were listed in the previous year’s directory, names of partners or forwarding addresses or post offices for people who’d moved away.

Many city directories identify African Americans by race, adding (c) or (col) for colored or (Neg.) for Negro. The 1922 Baton Rouge, La., directory, for example, states that “Names marked * are those of colored persons.” Some directories in Southern states have entirely separate “colored” sections. Directories may be inconsistent, identifying African Americans by race one year, but not in other years. Use addresses and occupations you find in other records, such as vital records, to confirm that a city directory entry is actually for your family.

Genealogy subscription sites such as Ancestry.com, Fold3 and MyHeritage have large collections of city directories, making it easier to find folks when you don’t know exactly where they lived in a particular year. The Online Historical Directories Website can help you find online directories on library and other sites. Otherwise, check local libraries, which often have print or microfilmed city directories for nearby towns.

Once you’ve found family in censuses and/or birth, marriage and death records, look them up in city directories for every year they’re available. Add each listing to a timeline to locate relatives in their place of origin, where they ended up, and as they moved along the way. Follow their moves to new addresses within a city, find working women, adult children living at home and widows, and document occupations and employers’ names.

You also can locate neighbors using the “cross listings” section, which lists residents by street name, and find the churches, schools, funeral homes, cemeteries, hospitals, benevolent associations, newspapers and stores your family may have patronized.

In the 1909 city directory for Springfield, Ohio, Sarah’s mother Tena Enoch was identified as the widow of Bedford Enoch. She lived in the same household as her granddaughter (Sarah’s daughter) Minnie, who was married to a man named Alexander, on 237 Fair. Listed nearby is Tena and Bedford’s grandson John L. Enoch, a grocery store owner, and his wife, Lillie. Alexander’s brother David Long, a laborer, lived at 633 Miami with his wife, Bertha E. Censuses and vital records show how the Long family intermarried with the Enochs in North Carolina and migrated to Ohio starting around 1900. By finding them year over year in directories of Springfield and nearby Xenia, Ohio, I can follow them as they moved North and lived with relatives, then got jobs and separate directory listings.

Search Military Records

Chances are good you’ll find a male relative in military records. WWI and WWII draft registrations can yield valuable information: birth date, birth location, age, physical description, profession, spouse and/or employer. WWI records also reveal a man’s residence in the gap between the 1910 and 1920 US censuses. This may be your first indication of a relocation, as the war accelerated the Great Migration by creating relatively high-paying industrial jobs.

Twenty-four million men between ages 18 and 45 (born between Sept. 13, 1873, and Sept. 12, 1900) registered for the WWI draft. Three registrations occurred between 1917 and 1918. Cards used for the 1917 registration instructed the registrar to tear off the lower left corner if the applicant was Black. You can search and view WWI draft registration cards at FamilySearch.

More than 10 million American men ages 18 to 65 registered for the WWII draft starting in November 1940. Ancestry.com has a database of cards from the fourth registration—the “Old Man’s Draft”—which for privacy reasons is the only WWII registration currently available to the public. Unfortunately, the cards for Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina and Tennessee were destroyed before they could be microfilmed or indexed.

The WWI draft registration record for Robert B. Clark indicates he was born Dec. 11, 1881, in Norwood, East Feliciana Parish, La. When he registered in September 1918, he was 36, a carpenter for Mason & Stanger in Jacksonville, Tenn. His wife, Cora, lived in Norwood. Family legend had it that Clark was African American and was so light-skinned that he could pass for white. Indeed, the draft card identifies him as white.

Clark lived long enough to also register for the WWII draft. At age 58 in 1942, he lived with one of his children, Sybil, in Chicago. His birth year was different from the WWI draft registration, but the birth date and place, Norwood, La., are the same. Clark was a janitor for Drape & Kramer, 341 E. 47th, in Chicago. Race isn’t noted, but his “light” complexion is. Inconsistencies aren’t unusual in historical records, so once you find a man on a draft registration card, confirm his identity by matching the information on the registration with the other records mentioned here.

Read Historical Newspapers

Don’t overlook newspapers as a resource for your African American ancestors. You’ll find people in news articles, obituaries and tributes to aged former slaves. You might find a family’s impetus to move: As noted, African American newspapers encouraged Black Southerners to migrate.

Some Northern newspapers had segregated “Colored Society” sections similar to the one published in the Xenia Daily Gazette in Ohio. The Gazette covered an area near two historically Black colleges, Central State University and Wilberforce University. The paper published its “Colored Society” section sporadically throughout the early 1900s, reporting such items as visits from family and friends, church events, deaths, weddings and illnesses.

Subscription website GenealogyBank has a collection of African American newspapers. Forty-six African American newspapers are digitized on the Library of Congress’ Chronicling America website. Choose the Advanced Search tab to search for a person by state and, if you want, a specific newspaper. Click the US Newspaper Directory button to search for microfilmed newspapers you can find in libraries.

Look for the Formerly Enslaved

Thousands of former slaves survived into the 20th century, whether they were enslaved as children or were freed adults who moved North with their families at an advanced age.

Once you find your family in the census, look for their age and state of origin in the South. Do the math: If the person was born before 1865, look for confirmation that the person is a former slave.

For men, check 1910 census column 30, which records “Whether a survivor of the Union or Confederate Army or Navy.” Your relative may have been one of the 180,000 free African Americans and former slaves who enlisted in the Union Army’s US Colored Troops (USCT). A USCT veteran will have UA in column 30. Next, search for the name, rank and unit in the Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System, an index of men who served in the Civil War, along with regimental histories. The compiled service records are at the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, DC, and digitized on Ancestry.com.

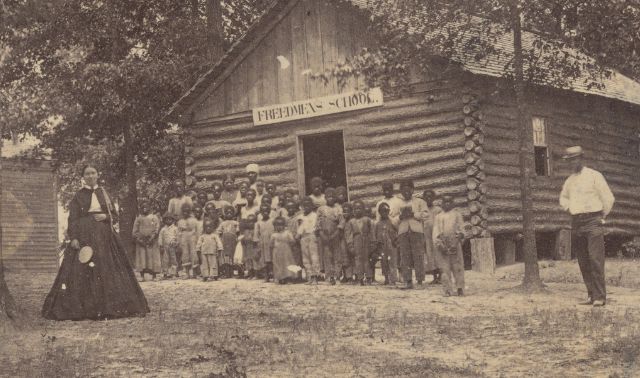

A rich source of information is in the collection of transcribed interviews with former slaves created by the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration in the 1930s. It contains more than 2,300 first-person accounts of slavery and 500 black-and-white photographs of the former slaves (though some are blurry).

Former slave and USCT soldier William Emmons of Nicholas County, Ky., was interviewed in 1941 at age 93. He lived with his son, Guy, the last surviving child of 12 with his second wife, Eliza. His narrative is a treasure trove of information: where he was born, the names of his former slaveowner and his parents’ slaveowners, the number of his siblings, when he joined the USCT and where he lived following the Civil War. You can search the slave narratives on Ancestry.com and on the Library of Congress website.

By thinking like an immigrant and mining genealogical records for place-of-origin details, you can fill in the details of your African American ancestors’ migrations in search of equality and opportunity.

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the January/February 2016 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: June 2025