Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Land records are among the most underutilized resources for genealogy. One of America’s major attractions to immigrants was the ability to obtain land.

In the established countries of Europe, almost all the land had been titled for years, even centuries. Laws of primogeniture (inheritance by only the first son) ensured that properties wouldn’t be split into too-small parcels, but they meant other children couldn’t inherit land. In America, though, residents could amass large estates and distribute their land however they wished. All of a man’s sons—and later, his daughters—could be heirs to his estate.

Land records were the first records created in new areas opened for settlement. As land changed hands through purchase and sale or inheritance, establishing records of ownership was important.

We will help you effectively use land records by understanding what records are available, what they include, where to find them, and how to use them.

Types of Land Records

Available land records vary by time and place. But in general, two types of records exist: patents (also called grants) and deeds of sale (deeds, for short).

The primary difference in these records is who’s doing the granting or selling. In a patent or grant, a government is the grantor of land. But a deed notes the subsequent transaction between private parties, even if either is a business.

All of the following types of land records can provide a wealth of information to help pinpoint residences, determine wealth or identify ancestors.

Patents/Grants

America’s first records of land ownership were created when a government granted land to settlers:

- The English crown made grants in New England, Virginia and its other colonies.

- France granted land in Louisiana and the Upper Midwest.

- Spain and Mexico granted land in Florida, Texas, and other parts of the Southwest.

- The United States granted land in federally owned states and territories, generally as they opened for settlement.

Given this history, there are two basic categories of US states when it comes to patent research:

- State-land states, in which a colonial power or the state/colonial government made grants: the Thirteen Colonies, Hawaii, Texas, Vermont and states made up from the original Thirteen Colonies (Kentucky, Maine, Tennessee and West Virginia).

- Public-land states, in which the US government made the initial grant: the other 30 states, most of them in the West and Midwest.

Grants specified the amount of property and usually the location. Especially in older records, land might not be described in terms of measurements. Rather, it will be described using landmarks or terms such as “far as the eye can see,” introducing the potential for duplicate, vague or inaccurate claims that later had to be settled in court.

Not all grants have survived. But later documents often refer to older grants, or deeds might transfer ownership to others by virtue of the original land grant. Grants may be accompanied by other supporting documents: proof of military service (for bounty land applications), naturalization papers (for Homestead applications), and so on.

Veterans of the American Revolution through the Mexican War were compensated with military bounty lands. Applications for bounty land warrants may contain important genealogical data, including military service details.

Deeds

After the initial grant, local offices (most often the county recorder’s office) handled subsequent transfers of property ownership through various types of deeds.

Deeds come in two main varieties. Warranty deeds are the most common and legally complete, in which the title of the land has been proven back to the original owner. The seller guarantees that he has the right to sell the land, and that no other parties have claims against.

Quitclaim deeds, on the other hand, indicate the sellers give up all of their own claims to a property, but cannot make guarantees about their right to sell it. They may be used in cases in which a missing heir could have a claim to the land, or if the deceased landowner did not leave a will. The surviving heirs were asked to sign the deed, and give up their interest in the property.

Sections of a deed

Deeds usually contain certain “boilerplate” phrasing, in addition to information on your ancestors and the property in question. That makes them somewhat easier to understand, once you have a sense for the typical structure of a deed.

- The introduction gives the date, names and descriptions of the parties, consideration (payment) being made, the grant (who’s getting what from whom) and any exceptions.

- The next two sections, which may be merged into one, indicate what interest in the property the deed grants, the party who has title to the land, any trustees and any conditions.

- A deed may have a section in which the grantor reserves something, such as mineral rights, for himself (or someone else), often using terms such as “yielding and paying.” For example, some early colonial deeds retain part of the property as rents for the crown that originally granted the land.

- In another section, the grantor warrants the title to the grantee. Rarely, covenants or conditions may require one or both parties to do something beneficial or abstain from something harmful. For example, a deed from a father to a son may require the son to maintain a home for his parents on the property. This often is seen when the father expects to die soon and wants to ensure his widow is cared for.

- The conclusion mentions the execution of the deed and the date, either expressly or by reference to the beginning of the document (“here above written”). It names the witnesses and bears the parties’ signatures, followed by the seal.

Many jurisdictions required a widow’s examination until the early 1900s. A wife was entitled to “widow’s rights” or “dower rights” (typically a third) of her husband’s property, although she often could not directly control or sell it in her own right. This was supposed to ensure that if widowed, she wouldn’t become a burden to the community. She was required to sign a statement that she was aware he was selling the property and she was losing her dower rights to it.

It’s a good idea to read several deeds before and after the one of interest to determine whether it varies from the typical wording of that time and place. Major variations should raise a flag of something worth investigating further.

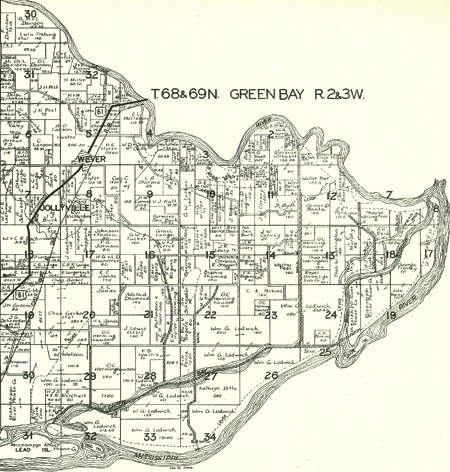

Plat maps

Plat maps show the precise locations of properties. Where available, they can put the land into context with names of your ancestor (and his neighbors), and locations of towns, roads, waterways, lakes, churches and schools.

Locating Land Patents

Before 1908, patents for land were filed by state land office, or by the act under which they were sold. After 1908, each patent was assigned and filed by a unique number.

The federal government holds copies of patents issued in public-land states. You can search for them by name or location at the Bureau of Land Management’s General Land Office Records site. See a tutorial for the site.

Once you locate a patent, order the land entry case file from the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). Use form NATF-84, or submit a request online.

You will need additional details when requesting pre-1908 records. The required fields depend on geography, as indexes have only been created for certain Western public-land states:

- Eastern states: Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Ohio and Wisconsin: type of file, name of the land office, and the land entry file number

- Western states: California, Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, New MExico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Dakota, Washington and Wyoming: legal description of the property or the type of file, name of the land office, and land entry file number

Copies of land entry case files from NARA cost a fee, but there’s no cost if staff can’t find the record you want. If you pay by check, NARA will invoice you before mailing the file.

For surrendered military bounty land warrant files, you’ll need the warrantee’s name, the year of the act, the warrant number and the number of acres. Search the BLM site to find this information if the warrant was used. If not, check the person’s military pension records. See NARA’s guide for more details on obtaining the warrant number from the military files.

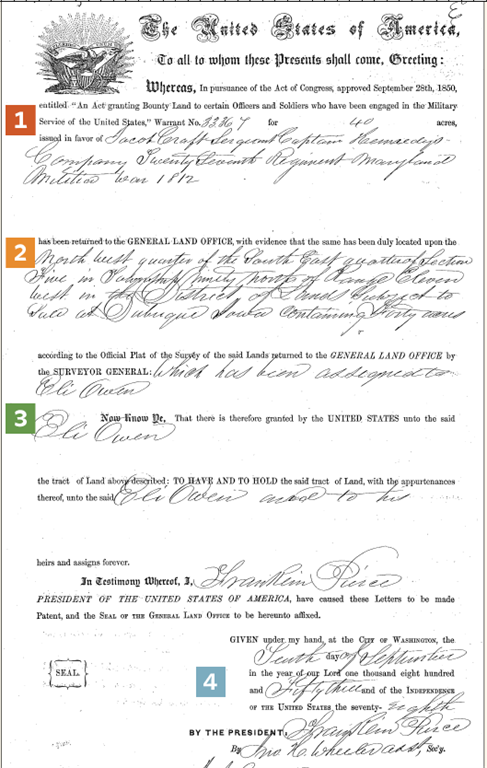

Sample Land Patent

1. The recipient of the bounty land is listed (Jacob Craft) on the warrant, along with the qualifying military service. Do not overlook researching this service.

2. The legal description of the property being transferred is called aliquot parts. Plat maps can help you pinpoint the location of the property.

3. The grantee may be another party (Eli Owen, in this case) to whom the land was transferred. Many warrantees sold or gave their grants to others, rather than occupy the land themselves.

4. The document was signed and registered 10 September 1853. A secretary signed the name of President Franklin Pierce.

Locating Deeds

Unlike federal land patents, deeds are not centrally located. Rather, they were recorded in the county that had jurisdiction over the property at the time, usually at the county recorder’s office (an office of the courthouse). Old deeds may still be there, or they may have been sent to a state archive or other repository.

If you are unsure of the right county to search in, consult references such as Land and Property Research in the United States by E. Wade Hone (Ancestry). Even if the county boundaries moved later, the deed would have stayed in the county that recorded it.

If you’re not sure where your family lived, check US census records and city directories for clues. Once you have an address, use a source such as Redbook: American State, County and Town Sources or the online Atlas of Historical County Boundaries to determine if the boundaries have changed. The more background information you have, the easier it’ll be to find family deeds. Follow these tips:

Online

Although not many deeds are online (yet), you may get lucky. More likely, you’ll find contact information for the repository that has your ancestor’s deed, and/or an index that’ll help you request it.

Search Google or another search engine using the county name and deeds. Browse Cyndi’s List for links to websites with useful information on land records, deeds and homesteads. Go to USGenWeb, a free, volunteer-run genealogy network, and navigate to your ancestors’ state and county—you might find digitized records, indexes and instructions for obtaining deeds.

Your best bet for finding deeds is to run a place search for the county in FamilySearch’s online catalog. Look for deed records listed under “Land and Property.” If FamilySearch has digitized the records, the listing will link to the collection. Note that some collections may only be viewed at FamilySearch Centers.

Indexes

Whether you are using microfilm, mailing a request to a court clerk, or visiting a courthouse, your search will be easier if you first can find an index to the county’s deed records.

Indexes may be in the beginning of each volume of a county’s deed books, or in a separate volume; they would be microfilmed along with the deeds. A local genealogical society also may have transcribed and published deed indexes online or in books you can borrow from libraries.

Deed indexes have columns for the grantee’s and grantor’s names, date of recording (which may or may not be the date of the transaction), type of transaction, volume and page number of the original deed, and the property location.

Some courthouses have separate indexes for grantees’ and grantors’ names. Others may combine grantees and grantors in the same index, with the transaction indexed twice (or possibly more if multiple parties were involved).

When there are multiple sellers or buyers, the index may include only the first name followed by et. al. (“and others”). If you don’t find the listing you expect, look for others who may have been party to the deed or check all the deeds indexed with et. al. Online deed indexes also may include every name listed.

Most indexes are not strictly alphabetical, but are grouped more or less chronologically by the surname’s first one or two letters. This makes sense given how the indexes were created: Names were entered on the appropriate page over time as transactions occurred, or periodically in groups. Look through all the entries for the letter of the alphabet you’re seeking to find names that may be out of place or misfiled.

Record the index information for the deed(s) you need on the free downloadable grantee and grantor index forms.

Tip: Deed indexes are usually arranged by the first letter or two of the grantee’s or grantor’s surname, but aren’t strictly alphabetical beyond that.

Courthouses

If you are using microfilm, look at the roll with the deed volume you need. At the courthouse, pull the deed book. If you are mailing a request for the deed to a county courthouse, check online or call for any fees and instructions. Include the information you found in the index, or if you could not find an index, provide the name of the grantor and/or grantee, the transaction date and the location of the land.

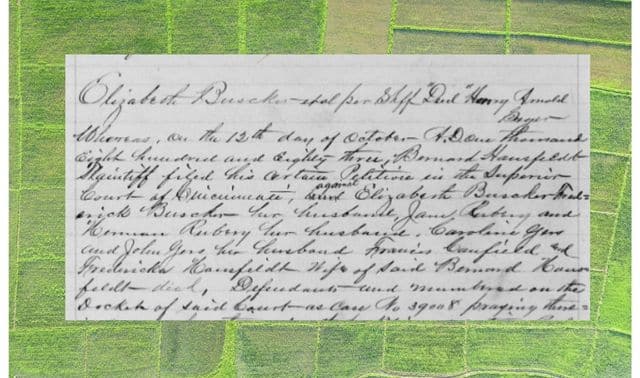

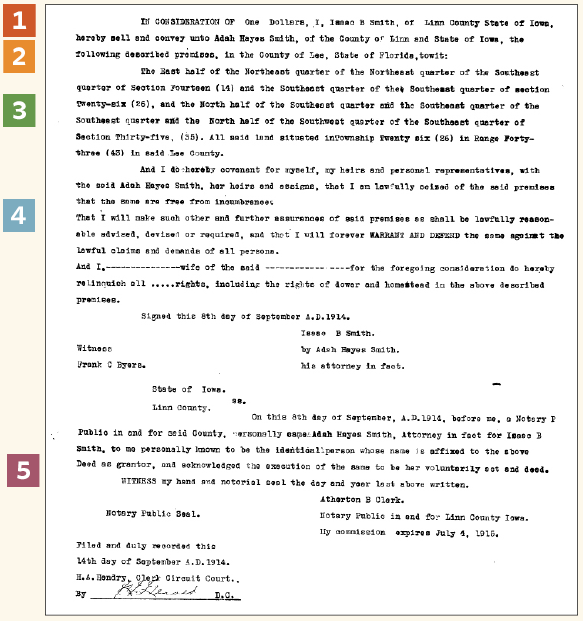

Sample deed record

1. The consideration of $1 may or may not be significant. Other deeds for this area commonly show consideration of $1, even though the actual transaction was for more.

2. The parties resided in Linn County, Iowa, but the land is in Lee County, Fla. The deed was created and signed in Iowa (where a copy may exist), and entered into the records in Florida.

3. This deed contains several parcels of land. They aren’t all contiguous, but are in the same vertical tier of the township.

4. The assurance that the seller owns the property and it is free from “incumbrance” and the “warrant and defend” clause indicate this is a warranty deed.

5. A lack of a widow’s examination might mean an unmarried seller, but other records show Adah Hayes Smith was the wife of Isaac B. Smith. The notary states that Adah signed voluntarily.

Finding Clues in Land Records

Transcribe deeds

To get the most from a deed, fully transcribe it (even though you may have a photocopy). This will force you to look at every word. Do not make any corrections; transcribe exactly what’s in the document, including misspellings, punctuation and new paragraphs. Even include words that were written in or marked out, with appropriate notations in square brackets [ ] to indicate what was added or struck.

What appears to be “wrong” may have been intentional. For example, if a list of grantees lacks commas, it might not be clear whether there are one, two or more people. For example, “John Jacob James and William Jones” could actually mean John Jacob James and William Jones (two people) or it could mean John Jones, Jacob Jones, James Jones and William Jones (four people).

Never assume anything until you’ve done additional research in other documents. For ease of use in the future, abstract the important information from the deed as a summary.

Do cluster research

Deeds often mention neighbors in the property description. Witnesses for all types of deeds were usually neighbors, friends or relatives. Plat maps show neighboring landowners.

Look carefully at these witnesses and neighbors: They may be in-laws, cousins or siblings. If your ancestral family was new to the area, see if those witnesses were, too—perhaps they arrived together from a previous home. Tracking a cluster of travelers may be easier than tracking one person or family.

Neighbors often can lead to the families of spouses. In the days before cars, the families of a young couple who married usually lived within about three miles of each other. Why? Courting was done after chores, which meant a young man had to walk (or ride horseback) to a young lady’s home and back before bedtime.

If a male relative married an Elizabeth, look at neighboring households for a missing Elizabeth. Then look for connections between that neighboring household and your ancestor’s family: Did Elizabeth inherit property from the neighbors? Did they witness your family’s deeds? Did they exchange land for surprisingly small sums of money? These circumstances are added support that you’ve found the right Elizabeth.

Tip: Skim other deeds surrounding your ancestor’s to become familiar with the handwriting. This will make it easier when you analyze your ancestor’s deed.

Study relationships

When heirs sold the inherited land, the source of the land was often part of the deed’s land description. For example, John Smith might sell “the land John Smith’s wife obtained from her father Michael Brown, on his death.”

When a parent gave land to a child (usually a son who’d reached adulthood; sometimes to a daughter through her husband at marriage), the deed may bear a statement of the “consideration” (payment) such as “for love and affection” or some very low price (such as a dollar). Other records or a later deed for sale of the property may confirm a relationship.

Learn the history of the land itself

“Following the dirt” may lead through an undocumented change of hands. Person A sold to person B, but person C later sold the land. How did it get from B to C? These cases nearly always indicate transfers by inheritance, not by sale, so look for person B’s will listing person C as an heir.

The other possibility is that the land “moved” in and out of the jurisdiction when boundaries changed, leaving a transaction for the transfer from B to C in another courthouse. For example, land in and near the current-day town of Tiverton, RI, has been alternately claimed by Rhode Island and Massachusetts over the past 350 years.

Understand local politics

The dates in a Colonial deed may give a clue to the politics of the grantor by indicating dates as being “in the 3rd year of the reign of King George III.” This wording (referred to as “regnal dates”) was most often encountered before or during the Revolutionary War, and might indicate a Loyalist.

Land records research is not just for rural ancestors. City residents owned land, too. Even renters could create land records, although they’re usually in the name of the landlord. If you have an address, look for property ownership records. You may be surprised at how much you learn when you dig through the records.

Fast Facts

- Records begin: with earliest settlement and continue through the organization of each jurisdiction

- Key dates: 1785, when the Land Ordinance Act authorized the US Treasury Department to survey and sell public domain land; and 1862, when the Homestead Act allowed settlement of public lands in exchange for improvement and cultivation of the land (the act was repealed in 1976)

- Key details in land records: names of grantee (recipient of the land) and grantor (seller), date of transfer, location of property, terms of transfer

- Search terms: county name, deeds, land grant, land entry case file, land patent, bounty land grant

- How to find in the FamilySearch catalog: Run a Place search for the county and state. Scroll to Land and Property, then browse for the record type and time period.

- How to find at a courthouse: Call or check online to find out if old deeds have been moved to another repository. Search deed index volumes covering the years of interest. Use the volume and page number listed to find the deed.

Land Records Resources

Websites

- Cyndi’s List: Land Records, Deeds and Homesteads

- Illinois Public Domain Land Tract Sales

- Indiana State Archives: Land Records

- Kentucky Land Office

- Massachusetts Registry of Deeds

- Platting the Land of Your Ancestors

- Missouri Digital Heritage Land Patents Database

- New Mexico Land Grant Records

- Oregon State Archives: Land Records

- Pennsylvania State Archives: Land Records

- Spanish Land Grants

- Texas General Land Office Land Grant Search

- Virginia Land Office Patents and Grants/Northern Neck Grant and Surveys

Publications and Resources

- Bureau of Land Management

- National Archives and Records Administration

- Courthouse Research for Family Historians by Christine Rose (CR Publications)

- Land and Property Research in the United States by E. Wade Hone (Ancestry)

- Locating Your Roots: Discover Your Ancestors Using Land Records by Patricia Law Hatcher (Betterway Books)

- Researching American Land Records by Kyle Betit (Heritage Productions)

- Revolutionary War Bounty Land Grants Awarded by State Governments by Lloyd DeWitt Bockstruck (Genealogical Publishing Co.)

Versions of this article appeared in the January/February 2014 and January/February 2025 issues of Family Tree Magazine.