County courthouses can be intimidating places for family historians. There’s a bustle of present-day business that’s unwelcoming to lost genealogists. A maze of departments, courts and offices that don’t necessarily perform the same functions as in the past, and may or may not house the records a historical researcher needs.

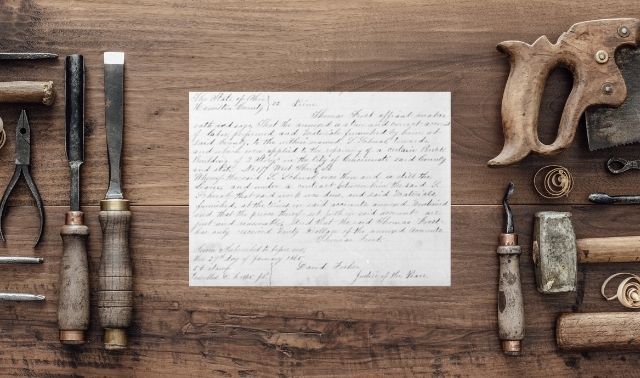

If you’ve researched at a courthouse, you might’ve encountered mysteriously organized indexes that reference daunting shelves of bound leather tomes. Your most-hoped-for records may not be anywhere in sight, and the documents that do mention your ancestors may be so packed with old handwriting and legalese as to resemble gibberish. Here is a complete guide to researching records both in and out of the courthouse.

1. Know the Records You’re After

A successful battle begins with a clear objective. In other words, you need to know what you’re after. These are five of the most important types of genealogical records likely to exist (at least for some time periods) at the courthouse, so make them your priority targets:

- County court records may name ancestors as jurors, witnesses, victims, even defendants or plaintiffs in civil and criminal cases. Naturalization applications, pension affidavits, divorce filings, separation or paternity claims, and other civil and criminal matters may all mention relatives as parties or witnesses. Look for the tactical advantage of indexes, usually one for plaintiffs (complaining parties) and one for defendants. Indexes and original civil, criminal and family court records are usually in the court clerk’s office.

- Property records document the sale or transfer of personal property and land, and may be scattered in different offices in the courthouse. For example, check the court clerk’s office for minute books with bills of sale for slaves, who were considered personal property, but check the recorder’s office to find deed books with deeds, mortgages and other land records, along with indexes to grantors (sellers) and grantees (buyers).

- Tax records for both personal property and land are among the least-utilized and most valuable genealogical records. Head (“poll”) taxes were usually assessed on males above a certain age. Personal property taxes help document what your ancestor owned. Land tax records may mention the amount, value and location of land owned, and even who the neighbors were. A tax collector, treasurer or commissioner of revenue often kept tax records separately from other court records. Ask at the county taxation or assessor’s office where old tax records are stored.

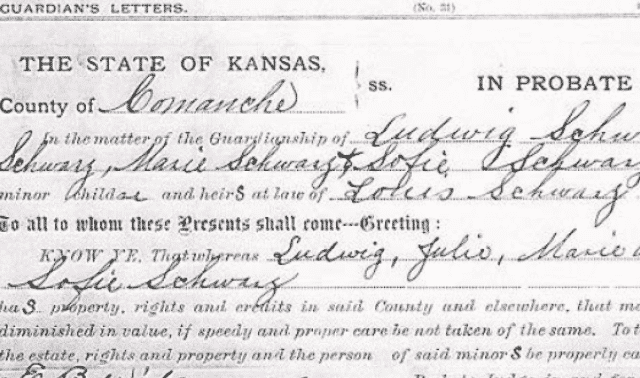

- Estate records are created when someone with property dies. The process of settling estates (often called probate) may include diverse records, depending on whether there was a will, whether anyone contested the division of property, whether guardians had to be appointed for orphaned children, etc. These records may appear in court minutes, probate files, estate packets, will books, inventory files and more. They may be kept in a special probate, surrogate’s or orphan’s court, or in a separate court of chancery, or with other court records in the court clerk’s office.

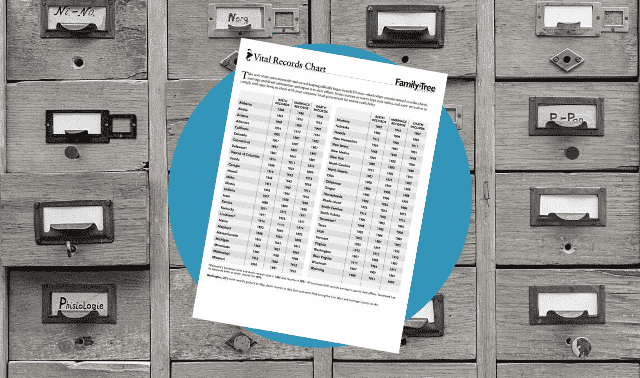

- Vital records (births, marriages and deaths) are on a genealogist’s most-wanted list, but not all are at the courthouse. Marriage records generally are, but birth and death records were often not required until the 20th century, and sometimes towns, not counties, kept vital records. (In those cases, start your search with the town clerk’s office.) Still, it’s always worth checking to see whether copies exist at the county level. Your first contact should be the County Clerk’s Office; check its website or call to ask about the availability of birth, marriage or death records during a specific time period.

2. Research Online and at the Courthouse

What if the court records you want aren’t in the places you’d expect them to be? You may need to conduct additional reconnaissance. These days, a two-front attack best conquers the courthouse: online and in person. Online research can lead you to a county website, contact information for courthouse offices, information (admittedly, of varying quality) regarding the location of specific records, and even online indexes. But follow up your online reconnaissance with an in-person advance for the most complete victory. Even the best web research and phone interviews won’t capture everything the courthouse has to offer. These strategies include elements of both approaches:

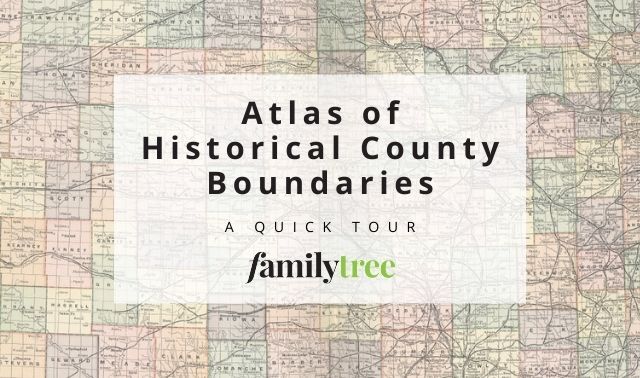

A. Research how county boundaries shifted

Figure out what you’re looking for before you go to the courthouse so you don’t go to the wrong one. It’s easy to look on a map and see that your ancestors’ hometown is now part of a different county than when he or she lived there. But that doesn’t mean you’ll definitely find their records in the new county’s courthouse. Arm yourself with knowledge of two important principles: parent counties and independent city governments.

In Colonial times and younger days of statehood, counties were often large. These “parent counties” divided as the population grew. When Texas was admitted as a state in 1845, it had 35 counties. Today, the same area has 254. Records for parent counties generally stayed put at the courthouses where they were created. So you’ll often find ancestors who lived in one place, but whose records appear in different counties as boundaries shifted. Use the interactive Atlas of Historical County Boundaries to identify which counties may hold your ancestors’ records for which time periods.

It’s important to know which county your ancestors lived in when they were selling land or suing their neighbors, and which county is now the administrator for that area. This type of history is important to check before you leave home, even if the ancestors in question never moved an inch after homesteading — the boundaries for the county they lived in may have.

Also consider geography. If your ancestors lived closer to the county seat of a neighboring county than the one in their own county, or if there were mountains or rivers in their way, they may have gone to the neighboring county to get married or transact business.

Some large cities have created their own county-like governments, or at least may have maintained records of their own. Depending on the dates and cities in question, you may need to contact a courthouse and/or a city hall to find records for people who lived there. Contact county offices to find out for sure.

B. Learn the various county departments

The different county departments and clerks in a courthouse can quickly become confusing. In some places in the past, such as early North Carolina, county courts and their clerks would’ve handled administrative as well as court matters (an example of administrative matters would be setting the yearly tax rate). But in other states, there were separate governing boards with a county clerk handling administrative duties and a court clerk for court duties. Hence the distinction: “clerk of the county court” vs. “the county clerk.”

Specialized county courts (such as probate and orphans courts), departments (such as health and transportation) and positions (such as tax assessor) have evolved over time, as have their responsibilities. Check the county government website for the area your ancestor lived to find explanations of their functions, how they changed over the years, and what records they created and kept. Look for information about exactly where the office is today and how to access the documents.

Other resources can help you determine ahead of time what records exist and where. The Family Tree Sourcebook: Your Essential Directory of American County and Town Records gives a rundown of records availability, which office has them, and the main county website and phone number. State or county genealogical societies or independent publishers may offer location-specific guides like Helen F.M. Leary’s North Carolina Research: Genealogy and Local History (North Carolina Genealogical Society) or Kip Sperry’s Genealogical Research in Ohio (Genealogical Publishing Co.).

Finally, before you go to the courthouse, call ahead to confirm the hours and any visitor rules. Ask if there’s a slow time of the year or week when visitors may have a better chance of getting help if needed. When you arrive, scout out the building. There’s almost always a first-floor directory where you can review all the departments, agencies and boards. Consider all the ways your ancestors may have interacted with the authorities to match that up with the offices that exist today.

C. Arm yourself with indexes

Indexes will list the name of the person in a record, where the record is (such as a volume and page number), and possibly other details, such as a case number or date. Some record types will almost always have indexes (property records, for example). Others will be much more hit and miss. Or indexes may exist only in the specific volume you’re looking at and not in a set of general indexes. Start your search—but don’t finish it—online.

Some county government websites host or link to online indexes. But mostly, look for indexes at county and state genealogical society websites, FamilySearch.org (browse by location down to the county level), and USGenWeb county sites. Follow any search tips provided on the site.

Printed indexes at the courthouse may be organized by date, alphabetically or semi-alphabetically by surname (for example, all the Bs on the same page, but first names are unalphabetized). Page through the index so you don’t miss anything, such as a separate page of surnames beginning Mc. Ask for help if you need it. Read more about indexing systems in Courthouse Indexes Illustrated by Christine Rose (CR Publications).

When working with any index, try to find out how and when it was created and how comprehensive it is. What years are covered? Is everyone indexed or just some parties? For example, are parents indexed in birth records, or just the child? Do witnesses appear in court indexes, in addition to the plaintiff and defendant? Are African-Americans in a segregated record set (common before the mid-1900s)?

Finally, look up ancestors in indexes under various spellings and name combinations. Blake Henry may be indexed as Henry Blake. Hannah Abigail DeMonte might appear as Hannah, Anna, Abby, H.A., or just Mrs. Charles DeMonte. And DeMonte might be under M instead of D. Misprinted or misread originals, spelling and typing errors, and other problems may also cause your ancestor to be indexed in unexpected ways. Look up different combinations—and log the ones you’ve tried on a form such as our Note-Taking Form.

D. Ask lots of questions

Sometimes an important source that names your ancestor is behind a desk, on a basement shelf or not even kept at the courthouse anymore. The staff there may not know about it or may not think to mention it to you. How will you find it?

First, read the spine or title page of every record book or register you can access. Look for your relative in it if there’s even a remote possibility he’s there. Then look over the types of records we’ve mentioned: Which ones haven’t you found? Identify the courthouse staff member who knows most about their old records. Ask questions (and take notes): Where are the licenses? Is there a business tax book? What office holds the voter registration records?

Some courthouse records may no longer be housed there. The court may forward old, bulky, fragile or valuable records to county archives, historical or genealogical societies, regional or state archives, or public libraries. Ask genealogical society volunteers and local librarians whether records exist and where they are. Locate genealogical societies on Cyndi’s List or search the web with the term genealogical society and the county name.

Widen your search by seeing what microfilmed or digitized records exist. The older and more basic the record type, the more likely the documents have been posted online or filmed (and the older and more fragile the record, the more likely you’ll be allowed to access only copies). Do a place-names search in the FamilySearch catalog with the format “state, county,” then select the right place from the menu that drops down. Follow directions in the catalog to rent microfilm through a FamilySearch Center near you. You can also see whether a state archives or library has microfilm holdings available via interlibrary loan, which you can borrow through a local library.

You may have to retreat and regroup if the records you want don’t exist today. You may be able to get around these limitations by finding alternative types of records from different sources, such as church records, military service and pension records, and local newspapers.

3. Understand Your Research Results

Triumph upon discovering a record can be short-lived if you don’t understand what the record means. Legal documents contain standard phrases and sentences laced between short bursts of unique information about ancestors. What you find may also contain clues for new research directions. Follow these steps to claim victory over your findings:

- Get examples. Read several examples of similar documents or registry entries to learn the boilerplate language. This will help you recognize anything unusual about your documents. When you come across an unfamiliar term, consult Law.com’s Legal Dictionary or Henry Campbell Black’s 1910 classic, A Law Dictionary Containing Definitions of the Terms and Phrases of American and English Jurisprudence at Google Books.

- Record all research results. Note your unsuccessful searches in addition to your successful ones. Not finding a document can be as valuable as finding one. A missing marriage record during an era when marriage records were kept may indicate an elopement or a marriage in the in-laws’ town. An ancestor’s first appearance in a tax list may mean he moved into town or came of age. If you have a reliable death record but there’s no will or probate, he may have had no significant property; perhaps he gave it away before his death.

- Extract your data. Summarize the important details from every document. Put these summaries where they’ll be easy to reference, such as on a large Post-It note on the photocopied record or in the comments field of your electronic bibliography. Or try using record transcription forms.

- Analyze the extracted information. What information have you won, and what new research frontiers can you pursue? For example, when you see family land deeded to someone for very little money, you may have discovered another relative is the grantee. If a man disappears from the tax lists and no evidence suggests he died, look for the sale of his property, purchase of land elsewhere (like a federal land grant), or even a criminal court sentence that would’ve sent him to prison.

If you’re not experienced in analyzing records, consult experts who are. You’ll find an excellent chapter on advanced courthouse research in The Family Tree Problem Solver by Martha Hoffman Rising. Find a chapter on gleaning clues from estate records in Courthouse Research for Family Historians: Your Guide to Genealogical Treasures by Christine Rose (Rose Family Assn). The Source: A Guidebook of American Genealogy by Loretto D. Szucs and Sandra Hargreaves Luebking (Ancestry) explains court, land and vital records in exquisite detail.

As you can see, a courthouse conquest can spell major victory for your genealogical research. You may need to muster up some courage before your first visit, but you’ll quickly gain battlefield experience. Before long, you’ll be a veteran enjoying the spoils of war—those battlefield trophy documents you can collect only when you conquer the courthouse.

Tip: Record all research results, including negative ones. Not finding a document can be as valuable as finding one.

Tip: You’ll often find ancestors who didn’t move, but whose records appear in different counties as boundaries shifted.

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the May/June 2013 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: July 2025