I come from a long line of immigrants. I’m a third-, fourth-, fifth-, and sixth-generation American. But I also have strong roots in the soil of southern Italy, the farmlands of southeastern Ireland, the potteries of England, and the Welsh countryside.

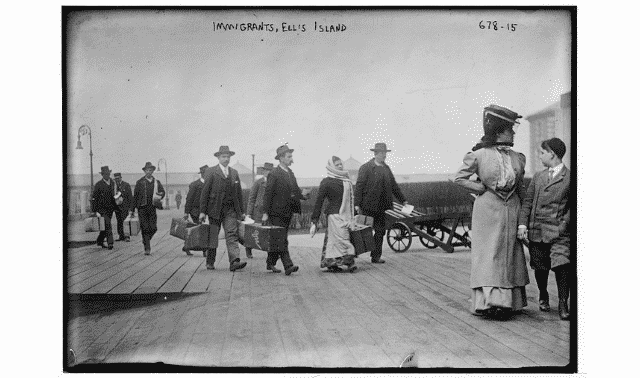

Most Americans can trace back their family history to immigrants—whether they arrived on the Mayflower, a Boeing-737, or sometime in the centuries between. Chain migration has been a main driver of population growth since the beginning of the United States, as individuals immigrated to reunite families or en masse to populate a new village. Forces in home countries also pushed people to immigrate: political upheavals, wars, oppression, famine and lack of economic opportunities.

As with most genealogy searches, you can begin looking for documentation of your immigrant ancestor at home. Passports or old photos may give clues to point of origin, as well as any family traditions. Family lore—even if fantastical or misremembered—might contain some fact, and stands to be proven or disproven using records.

Whether other records of your immigrant ancestors exist depends on when and how they arrived in the United States, and what (if any) interaction they had with the government after. In this article, we’ll discuss three key types of immigration records, plus a smattering of others. As we’ll learn, not all immigrants were even eligible to generate certain records, but documents—when you find them—will help you trace your ancestor back to the Old World.

Of course, not all individuals who arrived in the United States did so willingly. Around a half-million enslaved Africans were forced to come to this country from the early 1600s to the mid-1800s. And another large group never “arrived” during this time period at all—Native American tribes lived in the land that became the United States for thousands of years before European contact. Still others lived in Hawaii, Texas, or Mexican-, French- or Spanish- held land (including the Philippines and Puerto Rico) that was annexed or conquered by the United States.

This article discusses records of those who willfully came to the United States after European colonization; researching ancestors who were forced to come or found themselves on US land via other means requires different record sets and methodologies.

1. Passenger Manifests and Customs Lists

Perhaps the most consistent kind of immigration record is the passenger list—documentation that your ancestor arrived at a US port. But even this was not universally kept in early American history; the US government didn’t require this paperwork until January 1820, and even then, the lists were meant to regulate customs, not people.

As such, surviving pre-1820 passenger lists are few and far between. The best resource for them is P. William Filby’s Passenger and Immigration Lists Index, which indexes more than 500,000 early immigrant arrivals. A multi-volume series, the work is continuously updated to include later records and is available in its entirety on various online databases.

Records of arrivals after 1820 are much more widely available, including at major genealogy websites. Still, customs lists from this era (1820–1891) contain scarce information:

- name

- age

- sex

- occupation

- port of embarkation

With such little identifying information, you may have trouble distinguishing your immigrant from others, particularly if they had a common last name. After all, the lists were designed to track goods, not your immigrant ancestors.

The government federalized the process surrounding immigration late in the 19th-century. The new forms reflected a shift in focus to regulating immigration, ballooning in size from six columns to more than 20. In addition to questions asked by customs list, post-1891 records may include:

- place of last residence

- who the immigrant was going to join

- exact place of birth

- closest relative or friend in home country

- ability to read or write and in which language

With so much information, these records are rightly coveted by researchers with immigrant ancestors who arrived in this time period. Fortunately, many—though not all—are available and indexed on genealogy websites.

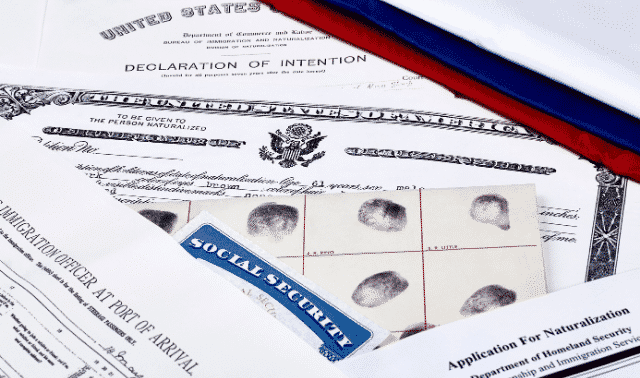

2. Naturalization Records

As it is today, naturalization was a goal for many immigrants and a source of pride for some families—though never, contrary to what some believe, required. With some exceptions, the standard road to citizenship has been a five-year process for immigrants.

From 1790 forward, free white immigrants could become naturalized US citizens after living in the United States for a number of years. But this privilege wasn’t extended to people of other races until much later: those of African descent in 1870 amidst Reconstruction and the Fourteenth Amendment, Chinese immigrants in 1943, Filipinos and Indians in 1946, and immigrants from other parts of Asia in 1952. The latter law, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, banned racial restrictions on most immigration and naturalization laws altogether.

An immigrant spouse or minor-aged child of a naturalized US citizen may or may not have automatically been considered a citizen, depending on time period and applicable laws. Beginning in 1855, a woman became a citizen automatically when her husband naturalized, or upon her marriage to a US citizen. But after 22 September 1922, a woman needed to complete her own paperwork to become a citizen, generating a separate set of records. Her process was expedited if she was married to a citizen.

Likewise, beginning in 1790, immigrant children under a certain age became citizens automatically when their fathers (or widowed/divorced mothers) naturalized. Later laws added residency requirements and changed the age at which children were no longer automatically granted citizenship.

Most naturalization records consist of two successive documents:

- Declaration of intention, or “first papers,” which could have been filed any time after arrival

- Petition for naturalization, or “second papers,” which was to be filed two or three years after the declaration (with a total of five years minimum since arrival)

However, some veterans were entitled to expedited naturalization starting during the Civil War. Starting in 1824, special consideration was also given to adults who’d spent at least three years of their childhood in the United States.

Note that there is no separate paperwork for spouses or children gaining derivative citizenship, nor are they explicitly mentioned on naturalization petitions until 1906. Their proof of citizenship was their marriage/birth certificate and the husband/father’s certificate of naturalization.

The government standardized naturalization in 1906, with administration shifting from local courts to a central agency (which would become Immigration and Naturalization Service or INS, today known as the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services or USCIS). Individuals generally naturalized in their county of residence, either at a local court (such as a common pleas court) or the federal district court with jurisdiction over their residence.

Prior to the change in 1906, naturalization records often don’t contain much information, with details varying by the court that kept them. At minimum, they contain:

- name

- residence (often just city)

- country of former allegiance

- date of the oath

As with early ship manifests, there may not be enough information in early naturalizations to confirm with certainty whether the record is of your immigrant. But naturalization records generally contain more information after the early 1900s.

One potential gold mine from this era, however, are records kept between 1816 and 1828. The US government required that aliens (i.e., noncitizens) register with the local district court, and that the information be included in naturalization paperwork. (More on alien registration records in the next section.)

Beginning in 1906, the standardized declaration of intention and petition for naturalization forms provide a lot more information to the genealogist:

- exact date and place of birth

- exact address

- port and date of arrival

- occupation

- names and birthdates of spouse and children

Helpfully, photos were added to the declaration of intention and certificate of naturalization (more on this shortly) beginning in 1929. Note that someone may have filed a declaration of intent but never a petition for naturalization, and that declarations of intention were no longer required after 1952.

Many naturalization records are online, especially at FamilySearch. But just as many are located offline, either in paper form or on microfilm at various libraries, archives and genealogical societies.

To search for naturalization records, start with the county clerk’s office or the county genealogical society. The county library or archives might also be able to assist in locating the records of interest. National Archives regional branches may hold federal naturalization records for states and/or territories in their jurisdiction.

There’s one other document from the naturalization process you should be aware of: the actual certificate of naturalization. Unfortunately, certificates of naturalization prior to 1906 generally haven’t survived outside of family collections. But starting in 1906, the government created two copies: one for the new citizen, and another for the government archive.

The latter is held by USCIS. That organization’s fee-for-service Genealogy Program holds C-Files (Certificate Files) for granted naturalizations from 1906 to 1956, including certificates of naturalization as well as supporting documents like declarations of intention and petitions for naturalization. C-Files are worth obtaining even if you’ve found all the constituent documents, as they might contain other records such as correspondence.

The Genealogy Program also holds some naturalizations for later years in A-Files (Alien Files). However, whether you can obtain an A-File through the USCIS Genealogy Program or a FOIA request, or via another federal agency (e.g., the National Archives) depends on several factors. Search the index to the Genealogy Program to learn if and where such records exist.

3. Alien Registrations

Aliens (nationals of foreign countries who were US residents but not yet citizens) were required at various times throughout US history to register with the federal or state government. The earliest instance of this was in 1798 as part of the Alien and Sedition Acts.

It wasn’t until the Civil War that aliens again registered with the government. In this case, alien men who wished to claim exemption from the Union Army draft could do so. Those who did appear in records now held across various regional National Archives branches, notably Kansas City.

World War I saw many alien registrations within the United States. German and Austro-Hungarian men and German women over age 14 had to register as enemy aliens between 1917 and 1918. While many of these records don’t survive, the ones that do are true genealogical gems.

Fast-forwarding a few decades to 1940: The government required the registration of all aliens over age 14 living in or arriving into the United States. Between August 1940 and March 1944, more than 5.5 million aliens filled out an Alien Registration Form (Form AR-2). These records, which cover people who immigrated as early as the 1850s, are held by the USCIS Genealogy Program. They contain invaluable information that may be found on no other US record. “Enemy” Aliens—aliens of German, Italian or Japanese origin as well as Americans of Japanese heritage—also registered separately during World War II.

The INS began filing all of an immigrant’s records together in an A-File (Alien File) in April 1944. Individuals who arrived on or after that date had an A-File created upon arrival, and individuals who had registered between 1940 and March 1944 should have had their files consolidated into an A-File upon any further contact with the INS. They are now held by the USCIS or the National Archives.

A-Files can get very confusing, as not all aliens had one. And A-Files don’t survive for all individuals who once had an A-File, as some were consolidated into other documents (such as C-files) if the individual naturalized prior to 1 April 1956. The best thing to do to determine whether an A-File exists (and, if it does, where it’s located) is to conduct a USCIS Genealogy Program index search. A simple search of the National Archives catalog would also reveal whether an A-File has made its way to one of their facilities.

Amidst World War II, alien men of fighting age also needed to fill out an Alien’s Personal History and Statement, a four-page form chock-full of genealogical details. Records survive for most states, and nearly all states’ records are with the National Archives of St. Louis. A few states’ records are available online.

Other Records

So far, we’ve just scraped the surface of the many documents available to those researching immigrant ancestors. I wrote a series of articles for FamilyTreeMagazine.com that serve as case studies for using records—especially less conventional ones, such as county histories—in your research; you can find them on this page.

Here are some other types of immigration documents worth special mention.

Detention and Special Inquiry Records

Beginning in 1893, arriving passengers could be detained if immigration officials believed they may have been ineligible for admission under various laws. Some examples include being a contract worker, a criminal, infected (or suspected of being infected) of a contagious disease, or otherwise a high risk of becoming a public charge.

Detention records also sometimes exist, showing individuals who were waiting to be collected by a relative or a representative of an immigrant aid society. Others may have needed funds to be telegrammed prior to continuing their journey.

Board of Special Inquiry and Detention lists exist for some ports.

Visas

Prior to the early 1900s, visas were not required for entry into the United States. If an individual could afford a ticket and the head tax (which began in 1882 at 50 cents per immigrant), they could immigrate.

But by the time an immigration quota system was introduced in 1921, visas were required. Beginning in July 1924, as part of the restrictive Immigration Act of 1924, visas and associated paperwork (like a birth or marriage record and a police clearance) were collected from each arriving immigrant after having been approved at a consulate abroad. These make up the 3.1 million Visa Files currently held by the USCIS Genealogy Program. (This series closed in April 1944. Visas were still required; they were filed in A-Files after that point.)

The National Archives at College Park, Md., has its own set of Department of State Visa Case Files (1914–1940). These records are different than the Visa Files, but an immigrant may be found in both record sets.

Bureau of Naturalization Files

Beginning in 1906, the agencies that became the INS kept correspondence files on specific cases. People may have written to the Bureau to check on their derivative citizenship status, or neighbors may have written to snitch on someone they thought had obtained citizenship fraudulently.

These records have been compiled by the National Archives, indexed in microfilm A3388. At time of writing, the collection is only available in the National Archives’ microfilm reading room. But researchers are hopeful at least the index will be made available online soon.

Our immigrant ancestors wrote our story; it’s time we write theirs.

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the January/February 2022 issue of Family Tree Magazine.