Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

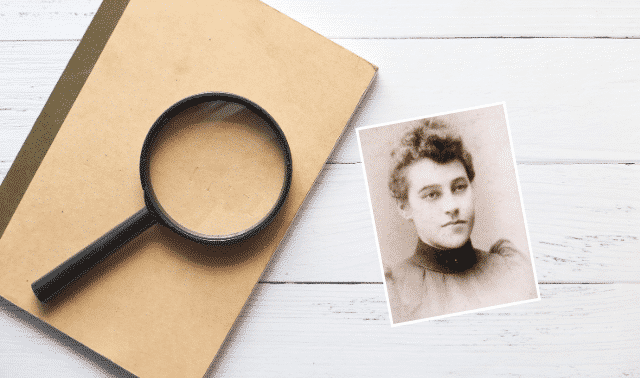

When she died in 1958, Alma Clark Chatham was laid to rest in Bellville, Texas, next to her husband, Walter. Her simple grave marker provides her birth and death dates, but just her married name: Mrs. Walter Chatham.

Fifty years after her death, Alma’s granddaughter visited the gravesite and asked, “Why is she not laid to rest with her name?” Only the person who bought the marker would know the answer to that question.

References to only “Mrs. [Husband’s Name]” are just one of many challenges that genealogists face when tracing women. Contemporary laws impacted women’s ability to own property, vote, and partake in the legal and political systems (including as citizens). That means many women were almost invisible in the eyes of the law—and invisible in genealogy records.

Recordkeeping is even more dire for women of color. Enslaved women, considered property, left few (if any) records. And despite the 19th Amendment in 1920, Black women couldn’t vote in practice in some parts of the country because of restrictive voting laws. Likewise, Puerto Rican women weren’t given the right to vote until 1929; in practice, most still couldn’t vote until a requirement on reading and writing was lifted six years later.

We need to meet challenges like these by considering location, history and the availability of the records that were created. Here are five common obstacles genealogists face when researching women—and how to overcome them.

1. I Don’t Know Where to Start

You may feel overwhelmed by how much you don’t know about a female ancestor. But as always in research, you should start with what you know, even if that’s not much.

Create a timeline for your ancestor that includes her name and every life event you know about her, even if you haven’t fully verified all the facts. Add details about her husband or children, if relevant. This should be a living document, meaning you add information to it as you work. Don’t worry that some of the details will need to be corrected later.

As you add information, consider what records you’d expect your ancestor to appear in. For example, say you know that a woman of interest married John Albert at some point after 1850, but you only know her as “Mrs. John Albert.” Look for John in the 1860 census and see what details it has about a wife. That, in turn, could lead you to the 1870 census or a child’s birth certificate.

2. What’s Her Name?!?

Maiden names are infamously difficult to learn, and present perhaps the greatest obstacle to genealogists. But a woman’s first name at birth can also be hard to find.

Fortunately, specific records tend to list a woman by her maiden name:

Marriage records

A marriage license or certificate includes information about the couple, including the bride’s maiden name. A resource such as the FamilySearch Research Wiki will help you determine what records are available. You’ll obviously need to search for the marriage record by the groom’s name.

Delayed birth records

In the 20th century, new benefits programs (such as Social Security) and forms of identification required applicants to have birth certificates. If the applicant didn’t already have one—for example, because they were born before vital recordkeeping was mandatory—they could receive a delayed birth record. This would include parents’ names and (if she was still alive) an affidavit from the applicant’s mother.

Death certificates

In addition to often including a maiden name, these may have named the deceased’s parents.

However, biographical details on death certificates are notoriously prone to error, as the informant may not have had firsthand knowledge of the relevant people and events. (And the informant’s grief in the moment could affect their accuracy even if they did.) Even surviving husbands might not be able to accurately name his late wife’s parents, especially if he never met them.

Obituaries

A woman’s obituary may mention her maiden name or specify the name of a parent, brother or unmarried sister. But women may also be included in obituaries for her parents or siblings, providing (if the deceased is her father, brother or unmarried sister) a solid lead for a maiden name.

Take care when viewing obituaries for a woman’s mother, though. The mother may have taken a different surname since giving birth to your woman of interest, perhaps because of a remarriage.

Children’s birth and death records

These sometimes specifically ask for mother’s maiden name. Recordkeeping laws vary by US state, however, so they may not be consistently kept. And different states may have asked for different details.

Military pension records

If a woman’s husband served in the military, she may have been eligible to receive a pension. The application required a bevy of supporting documentation, some of which might provide maiden name.

3. How Do I Research That Location?

Place is so important to genealogy research. You may have found ancestors in Western states but scratch your head when looking for other lines in a New England town. Those two areas of the country had vastly different histories, settlement patterns, and available records.

Approach your research as if you were a historian, considering the location and time period your ancestor lived in. Check out the FamilySearch Research Wiki for the state she resided in to learn what’s available. The wiki also has pages for specialized research topics, such as African American genealogy.

Then, determine where the records are located today. I recommend searching website card catalogs to find records for the time and location of interest. Drill down to country, then state, county and town to see what’s available:

- Ancestry.com: Separate fields for Title and Keyword (plus filters by place and record type) give you multiple options for identifying relevant collections. Alternatively, you can filter search results from anywhere in the site by location.

- FamilySearch: This includes materials digitized at FamilySearch, as well as those held by the FamilySearch Library in Salt Lake City and its affiliate branches around the world. You can also find collections from a specific place.

- MyHeritage: Click Refine by Location at left to see options for individual countries or US states, or the search field at top to filter using keywords.

But remember some records—notably, birth, marriage and death certificates—are not online yet. You’ll need to do your due diligence to identify and contact archives that hold physical or microfilm copies.

Family Tree also has research guides for all 50 US states, plus Puerto Rico and Washington, DC.

4. She Disappears Between Census Years

You found her in 1900, but not in 1910. Where did she go?

A lot can happen in 10 years. Families move, couples marry, and people die. For women in North America who typically change their surname upon marriage, she may seemingly vanish without a trace.

Searching by family member

How do you find her? Use what you know to your advantage. Consider details about her from the previous census: What was her name? Who was she living with? And what other biographical details do you have about the household?

Next, think about alternative terms to search for. We usually default to searching by a person’s full name, birth year, and location. But instead, you could search by the name of a relative (Was the woman living with a child?) or just by first name and birth year (Did she marry/remarry and have a different surname?). You can also toy with “exact” matches in databases, allowing you to account for misspellings or name variations.

Browsing images

In other cases, you’ll need to browse records, rather than relying on keyword searches. Use a site’s record-viewer to drill-down to the enumeration district where you think your ancestor lived, then page through records image by image. This may take quite some time in a large city. (Find tips here.)

Considering deaths

As previously indicated, it’s also possible your woman of interest died between the census years. Look for her in death indexes and collections of death certificates for that place and time, or peruse burials at sites like Find a Grave. Run a name search in historical newspapers for obituaries or death announcements.

You have an extra resource if you’re researching the 1850 through 1880 censuses: mortality schedules. These log deaths that occurred within the year preceding the census, and are available at Ancestry.com.

Before you “kill her off,” though, look for other records that might mention a woman in those in-between years: city directories, other newspaper announcements, or state censuses.

5. Why Isn’t She in That Record?

Great! You’ve found a record of your ancestral family. But that elusive woman isn’t listed. What gives? As we’ve already discussed, perhaps the woman died before a census was taken. But another possibility is that she was staying with a family member when the enumerator arrived.

Learning about how and why a record was created can also be enlightening. Perhaps a woman isn’t in a record because she’s not supposed to be.

For example, she wouldn’t appear in voting lists before women in that state had the right to vote. Women living in California could vote beginning in 1911 (pre-dating nationwide women’s suffrage in 1920), but my female ancestors in Texas could not. Other local issues—such as poll taxes and a woman’s own feelings about suffrage—might have hindered her voting.

City directories, too, often only mentioned women by their husbands’ names. Read the introductory pages of a directory to understand how residents were mentioned. Perhaps the directory was only to include heads of household by name.

Finding female ancestors can be tough, but not impossible! As these tips have demonstrated, there are several steps you can take before giving up on a mystery woman.

What about “Mrs. Walter Chatham”? I learned her long-lost name by first researching her husband. I had his birth and death dates, which I used to find his entry in the 1950 census. There was his wife, Alma.

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the March/April 2025 issue of Family Tree Magazine.