Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

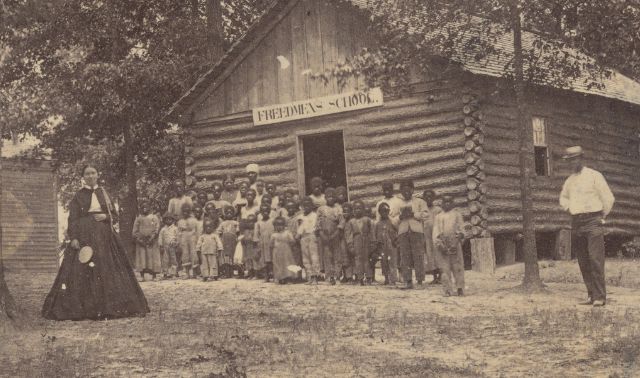

Researching enslaved ancestors presents unique challenges. To overcome them, you’ll need a blend of persistence, creativity and resourcefulness. After all, you’re tracing the lives of the obscured or erased—no small task.

With systematic research strategies and specialized resources, you can uncover the hidden stories of African American ancestors who lived through one of the darkest periods in US history.

This article includes eight case studies that show how renowned genealogists were able to trace their enslaved ancestors. Each highlights not just the enslaved’s status in bondage, but also the roles they played in their families and communities.

From general US records to special collections and from plantation histories to probate records, each resource brings us closer to reclaiming the lives of those who endured slavery.

Identifying the Plantation

The journey from freedom to enslavement begins in the 21st century, researching the descendants of the enslaved. As you cross into the 20th century, some records can provide direct clues about the family’s history, creating a paper trail to plantations and enslavers. Key records include pension records, death certificates and newspapers.

By being patient, thorough, and creative in your approach, you can uncover the stories of your ancestors and trace their paths back to the plantations they once lived on.

Case Study 1: Soldier, Fighting for the Union

- Researcher: Alvin Blakes

- Enslaved Ancestor: Phillip McWhorter

- Location: Louisiana, Mississippi

- Key Records: Pension records, estate inventories, wills, bills of sale, court records

- Advice: “Go beyond your direct line.”

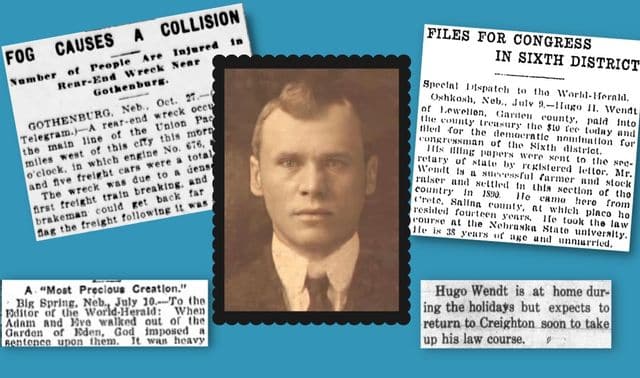

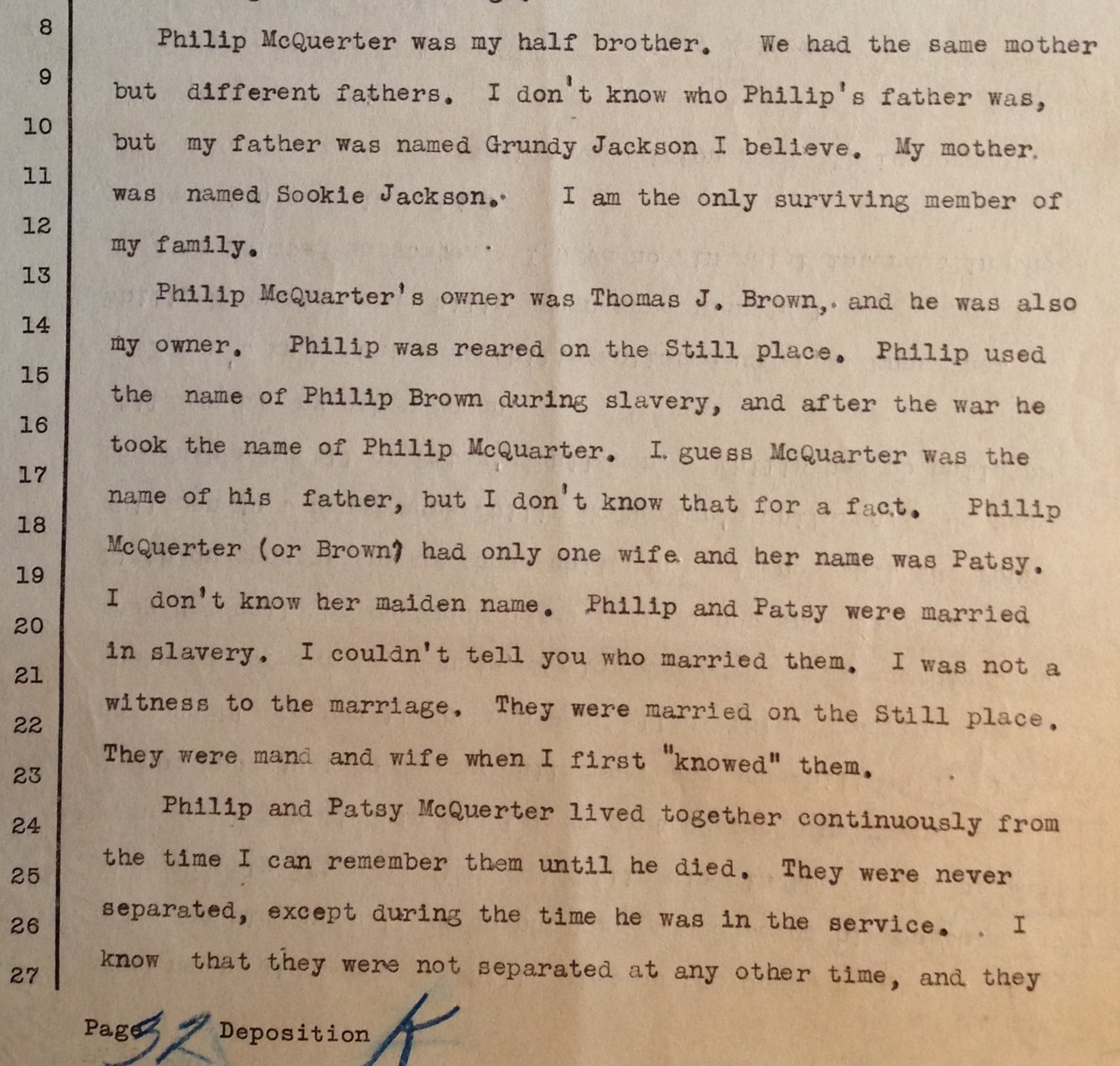

Phillip McWhorter rose to the rank of corporal during the Civil War, serving with the storied U.S. Colored Troops (company A, 81st regiment). His army pension application—filed by his minor children after his and his wife’s sudden deaths in 1899—included testimony from his roughly 80-year-old half-sister, Milly. She shared details of their family’s life in slavery, notably the name of Phillip’s owner and the name Phillip had during slavery.

Alvin Blakes, family historian and blogger at “Almost Disappeared: Unearthing My Family History,” used this testimony to trace McWhorter’s lineage all the way back to the Revolutionary War era.

Blakes was able to uncover valuable information by studying McWhorter’s reputed enslavers: the Brown family of Wilkinson County, Mississippi. From probate and court records, he learned that John Wilson Brown inherited the McWhorter family from his father in 1842. But he sold off his property (including most of his enslaved Africans) when he became ill in 1856.

Phillip was one of the few that Brown kept; Brown died the next year, and McWhorter was returned to his mother, Eliza Brown. Like men enslaved men in the county, Phillip left the plantation to join the Union army.

With systematic research strategies and specialized resources, you can uncover the hidden stories of African American ancestors who lived through one of the darkest periods in US history.

Case Study 2: Neighbor, Echoes Across Generations

- Researcher: Dr. Deborah Abbott

- Enslaved Ancestors: Jeremiah and Clarissa Dusenbury

- Location: North Carolina

- Key Records: Censuses, draft registrations, death certificates, wills

- Advice: “Don’t rush this process. Slow down and pay attention to everything that you pull.”

Even modern census, vital and military records can reveal connections to an enslaved past.

That’s why Dr. Deborah Abbott emphasizes the importance of thoroughly reviewing all records you find. She recalls one instance where two families—one white, one Black—who lived next to each other in the 1950 census and had the same surname were actually descendants of an enslaved-enslaver pair. Draft cards revealed an even more startling coincidence: a member of the Black family worked for a member of the white family.

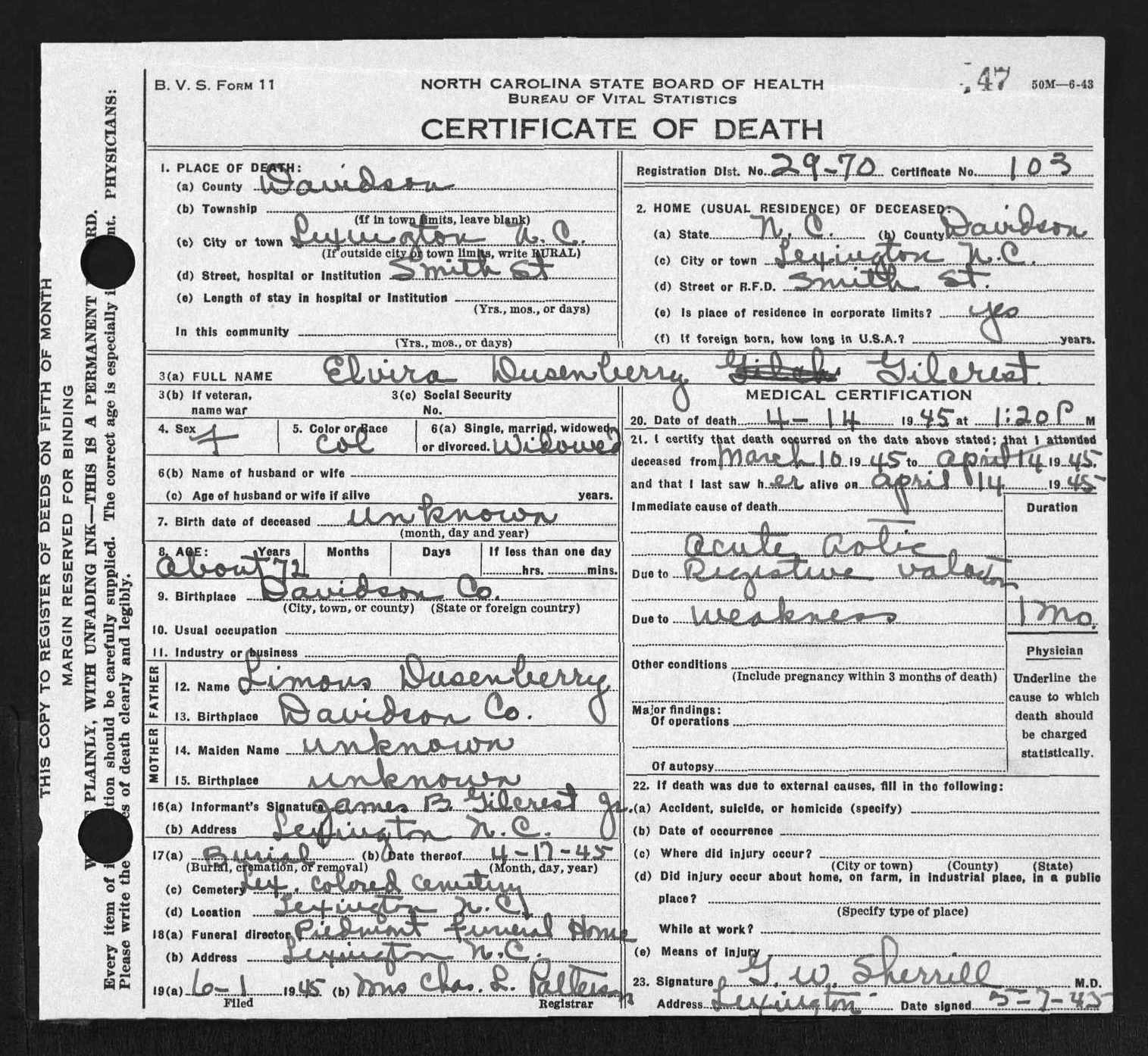

Another connection to the antebellum past emerged when Abbott’s friend Sandra Milton asked for help. Their search for a family in Davidson County, North Carolina, revealed a 1945 death certificate for an Elvira Dusenberry Gilcrest. That, in turn, led to researching the history of the funeral home.

Through that history, Abbott and Milton located Milton’s third-great-grandparents, Jeremiah and Clarissa Dusenbury. (Note the different spelling.) The Dusenburys were listed as “Jerry” and “Clarissy” in an 1829 will of enslaver Samuel Dusenbury.

Samuel, as it turns out, is the father of Henry Dusenberry, whose house became the funeral home where Elvira was laid to rest. Elvira was laid to rest in the home owned by the family who enslaved her ancestors.

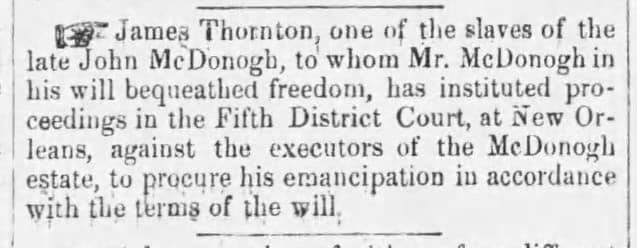

Case Study 3: Advocate, Petitioning for Freedom

- Researcher: Ari Wilkins

- Enslaved Ancestors: James and Fanny Thornton

- Location: Louisiana

- Key Records: Newspapers, petitions, plantation records

- Advice: “Be patient. Go over records again and again.”

Genealogist Ari Wilkins found her enslaved ancestor, James Thornton, in an 1852 newspaper article in which he petitioned for his freedom. His enslaver, John McDonogh (one of the richest men in New Orleans) promised that he’d emancipate the enslaved via his will. But a year after his death, they still weren’t free.

This article led Wilkins to a treasure trove: manuscripts of the McDonogh’s plantation, providing seemingly endless resources for viewing and re-viewing. These painted a vivid picture of life on the plantation and allowed her to uncover more about her ancestors’ experiences.

The manuscripts were further described in another collection, then indexed. FamilySearch has the records (including a detailed inventory of McDonogh’s property and drawings of his buildings) online.

Researching Plantation Life

The search for understanding continues even after you’ve reached the significant milestone of identifying an enslaver. What was everyday life like for the enslaved on the plantation? How were they affected by the debts or death of their enslaver?

These stories underscore the ways in which enslaved Africans were treated as property: bought, sold and divided among families. By gathering all of the probate records together (like wills, inventories, and court records) you can make discoveries that have emotional and historical weight. They provide invaluable insight into the resilience of those who endured such hardship and dehumanization.

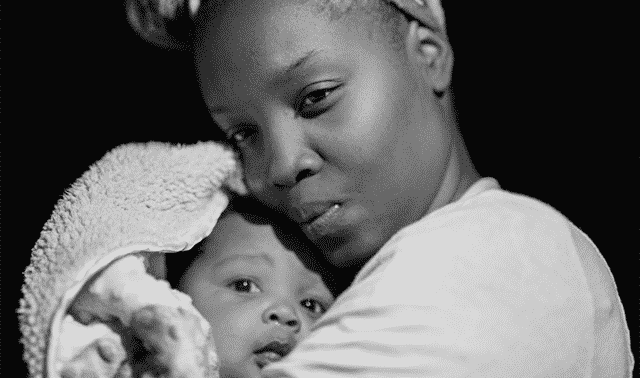

Case Study 4: Mother, Navigating an Uncertain Future

- Researcher: Sharon B. Gillins

- Enslaved Ancestor: Cordelia

- Location: North Carolina

- Key Records: Wills, estate inventories, court records

- Advice: “Study (and use) genealogy best practices.”

When Norman Branch died, his will (written seven years before his death) instructed that his 14 enslaved “negroes” be left to his wife. But upon his death, Branch had 22 enslaved individuals on his estate inventory.

Cordelia and her children were among those not mentioned in the original will. Cordelia had been traded for one of the 14. As a result, her and (especially) her children’s fates were uncertain.

Professional genealogist Sharon B. Gillins, found the Northampton County, N.C., will and estate records on FamilySearch. According to the latter, Branch’s son-in-law, William Lundy, filed a court petition demanding his wife (Branch’s daughter) receive her share of the estate. The judge complied, dividing Branch’s “intestate” property (that which wasn’t mentioned in the will) to inheritance laws.

This determined the fate of those not mentioned in the will. Cordelia and her family became the property of the Lundys, rather than staying with Branch’s wife. And the legal system treated them no differently than it would have a piece of land or some farm equipment—and they certainly had no say in what became of them.

Case Study 5: Pioneer, Reframing Longevity

- Researcher: Franklin Carter Smith

- Enslaved Ancestor: Moll

- Locations: North Carolina, Mississippi

- Key Records: Wills, estate inventories, court records

- Advice: “Immerse yourself in the community. Families are connected by community.”

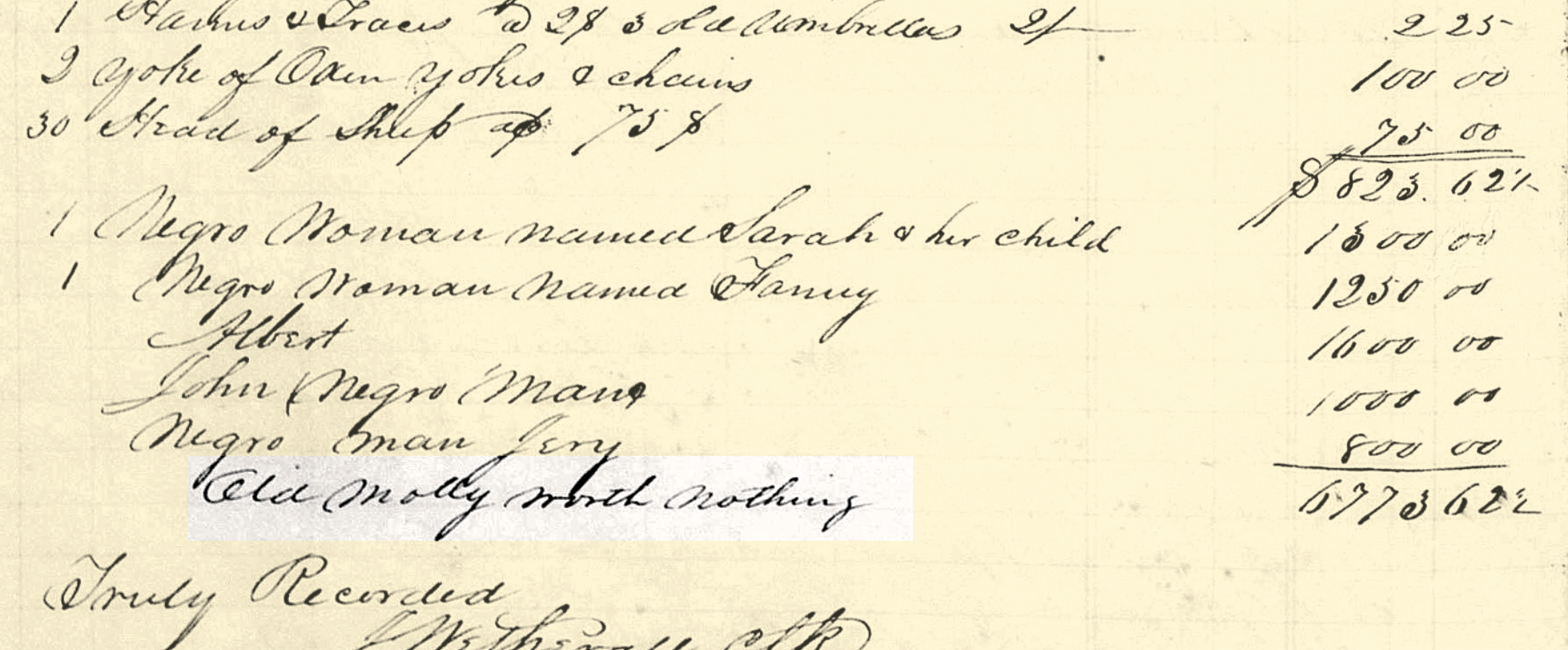

Seeing an ancestor listed in an estate inventory with a price next to their name is difficult. But seeing them valued at zero dollars can be even more disheartening.

In a Mississippi estate inventory from 1837, Franklin Carter Smith, co-author of A Genealogist’s Guide to Discovering Your African-American Ancestors (Betterway Books), found his fifth-great-grandmother, Moll. She was listed as “Old Moll”—worth nothing due to her age.

Yet to Smith, she was invaluable. “To me, she was worth her weight in gold,” says Smith. “She likely had to walk part of the way from Edgecombe County, North Carolina, to Mississippi. But she survived for her family and children.”

Smith traced Moll through seven enslavers, beginning in Edgecombe County in 1770, when she was 10 years old. Moll’s value in those early years was listed in pounds and shillings.

His research involved collecting probate, property, and court records to track the movement of Moll and her community from one inventory to the next. This meticulous work took years, but it allowed him to trace Moll and those around her.

Court records were particularly useful, as Moll’s last enslaver was underage at the time, making legal documents more detailed. Additionally, through genetic genealogy, Smith connected with other descendants of Moll, further enriching the story of her legacy.

For Smith, those deep roots provide deep meaning—and a sense of belonging. “No one can ever tell me to go back to where I belong,” Smith says. “I was here. I can document my existence before many got here.”

Beyond the Plantation

Freedom for the African was granted and taken away. Some took bold steps, while others were granted

it legally.

The following profiles explore the stories of individuals who fought for their own freedom, were legally manumitted, or even kidnapped. Through it all is connection—to family, to survival and (even) to African origins.

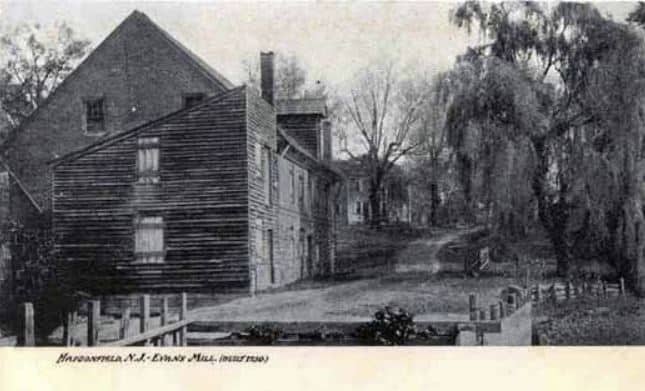

Case Study 6: Freedom Fighter, Starting a New Life

- Researcher: Paul W. Schopp

- Enslaved Ancestor: Alexander Hemsley

- Location: New Jersey

- Key Records: Slave narratives, court records, censuses, journals

- Advice: “There is a cornucopia of source material out there. You are only limited by your imagination.”

In the early 1820s, 23-year-old Nathan Mead fled enslavement in Queen Anne County, Maryland, to New Jersey. There, he took on a new name: Alexander Hemsley.

He settled in Evesham, Burlington County, then married and had three children with a woman named Nancy. But in 1835, an agent for the estate of Isaac Baggs sought to reclaim Hemsley as estate property.

Despite living in a free state, the family was detained. Nancy was released after establishing her mother had been free before Nancy’s birth. But Hemsley spent four months in jail before winning a case before the New Jersey Supreme Court. Fearful of being kidnapped again, Hemsley moved to Canada, where he became a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Hemsley’s story was included as part of the book A North-Side View of Slavery, The Refugee: Or the Narratives of Fugitive Slaves in Canada by Benjamin Drew, published in 1856. In it, Hemsley recalls his escape and life in New Jersey and Canada.

Fast forward to today: Paul Schopp, an assistant director of Stockton University’s South Jersey Culture & History Center, used that narrative to build upon Hemsley’s story. He found even more records documenting Hemsley’s life, including census data, court case files and a photo of the mill where Hemsley worked.

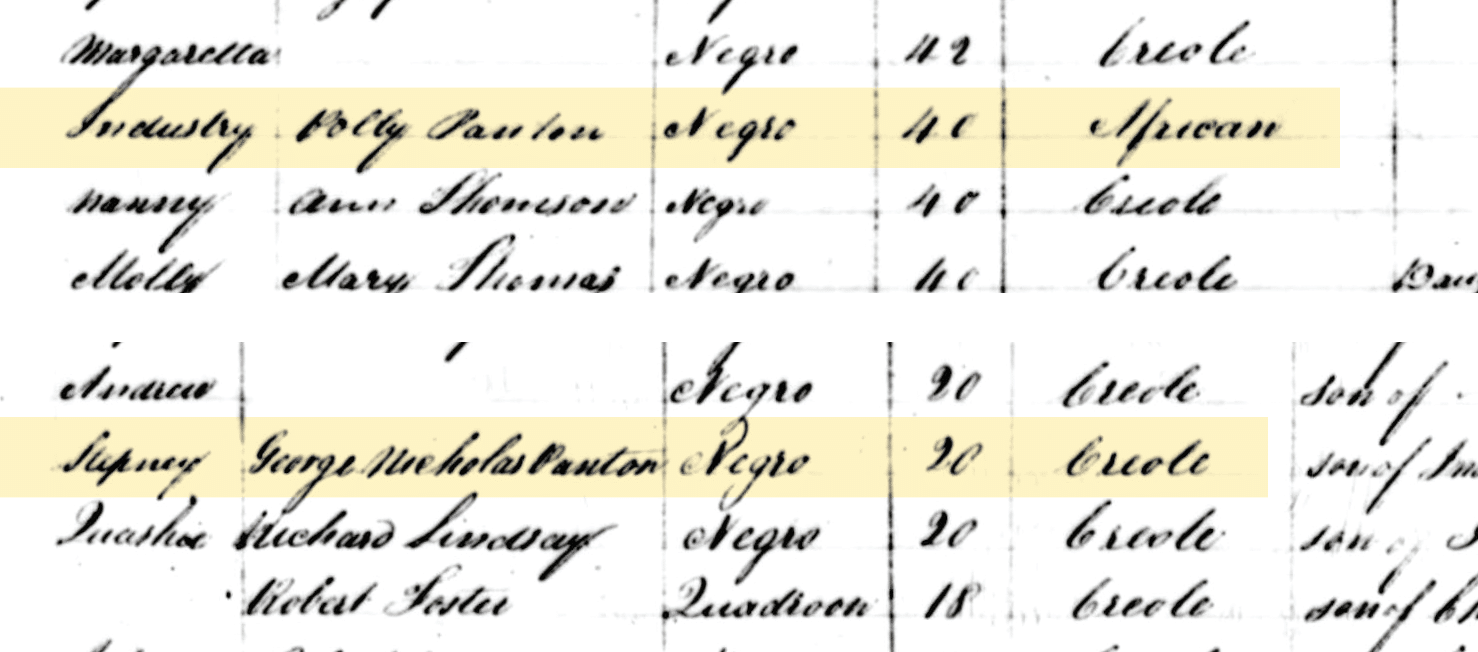

Case Study 7: Survivor, Reclaiming African Roots

- Researcher: Phillip Nicholas

- Enslaved Ancestor: George Nicholas Panton

- Location: Jamaica

- Key Records: Plantation records, slave registers, marriage records

- Advice: “Patience, patience, patience. TV makes it look easy, but it takes years to piece your family story together.”

Phillip Nicholas, founder of Genealogy Detective Caribbean, began tracing his Jamaican ancestry despite having limited information.

Starting with civil registrations, he gradually worked his way back to his fifth-great-grandparents. George Nicholas and Christina Hazell were married at Elmwood Plantation in St. Thomas, Jamaica, in 1822.

Nicholas used various records, including the British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme’s slave manumissions to trace his ancestors back to the end of the apprenticeship period in 1838.

Another document, the 1817 Slave Register, revealed that George was originally named Stephey and (at the time) was 20 years old, listed as Creole. George’s mother, Polly Panton, was 40 years old. She and her husband were both born in Africa under the name Industry.

For Nicholas, discovering Polly’s African origins was a powerful moment. He’d found the name of his ancestor who survived the transatlantic slave trade. “When I told my dad, it was emotional for him … to learn that I could actually find that in the paper trail,” Nicholas says. “To know exactly who in our family was West African—it was just powerful.”

Through years of research, Nicholas pieced together a paper trail connecting him to his African roots. He uses genetic genealogy to enhance his findings.

Case Study 8: Preacher, Overcoming Stigmas

By Kenyatta D. Berry

George Dwelle, the third-great-grandfather of my law school friend, sparked my interest in genealogy. My classmate was named after his ancestor, a prominent pastor of Springfield Baptist Church in Augusta, Ga. In Notable Black American Women, 3 volumes, edited by Jessie Carney Smith (Gale, out of print), I stumbled across a biographical sketch of Dwelle’s daughter Georgia Rooks Dwelle. I was hooked: I yearned to learn more about this family.

George was born Jan. 26, 1833, in Columbia County, Ga., the son of a slave and a white man. In the 1917 book The History of the American Negro and His Institutions, 6 volumes, by A.B. Caldwell (reprinted by Kessinger Publications), George identified his mother as Mary Thomas and his father as C.J. Cook, a white man from Connecticut. Mary was born about 1818 in Georgia and died between 1900 and 1910 in Augusta. Little is known about her, but it’s rumored she was living with a Dwelle family when George was born.

In the 1840 census, I found a Clark Cook living with a white male 20 to 30 years of age—presumably his brother Aaron H. Cook—and no slaves. (Remember, in pre-1850 censuses, only heads of household are listed by name.)

According to 1850 mortality schedules, Clark J. Cook was born in Massachusetts, and died in May 1850 at age 47 in Richmond County, Ga. Slave schedules list in his estate: a black female, age 30, and a male, age 17, presumably Mary and George. Census informants may have guessed at the slaves’ ages, and slaves often didn’t know their own birth dates, so age discrepancies are common.

With this information, I contacted the Richmond County courthouse for copies of estate records for C.J. Cook, aka Clark J. Cook. The papers show he migrated to Georgia sometime before participating in the state’s 1832 land lottery. When he died, his estate totaled more than $27,000. Its proceeds were divided among Aaron and his other three siblings.

Mary and George were sold at auction to Milo Hatch, Sept. 2, 1851, for $2,300. George brought in $1,500; Mary fetched $800. Hatch is listed in 1860 with four slaves: two black females, ages 50 and 45; a mulatto male, 25; and a black male, age 12. None match for George and Mary. But the same year, Aaron Cook has two slaves, a black female, age 40, and a mulatto male, age 26. Mary and George might’ve been hired out to Aaron Cook in June 1860 (that year’s census date).

George Henry Dwelle didn’t let the stigma of his skin color or former-slave status stop him from becoming a preacher. Two Englishmen in Augusta ran a clandestine school for slaves, where he learned to read and write by age 13. He joined Springfield Baptist Church in 1855 and was baptized the following January.

Dwelle was ordained and licensed to preach in 1874, and three years later, joined Eureka Baptist Church in Albany, Ga. The 85 members lacked a place to worship. In less than four years, Dwelle had purchased land and built a church. In 1885, he became a pastor at the church where he was baptized. He served Springfield Baptist Church until his retirement in 1912.

His daughter Georgia, whose biography spurred my search, followed her father’s example to become one of Atlanta’s first black woman physicians.

Researching enslaved ancestors requires determination and a willingness to delve into various historical sources that connect families to the past. The methods outlined in this article serve as a foundation for genealogists to navigate the complexities of tracing enslaved ancestors, helping to bridge the gap between freedom and enslavement.

By carefully analyzing historical records, leveraging special Black collections, and investigating local histories of slavery, genealogists can uncover the lives, connections, and stories of those once considered property. The discoveries not only shed light on family histories, but also honor the resilience and survival of enslaved individuals whose legacies live on in their descendants.

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the January/February 2025 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for site to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to affiliated websites.