Written by Maureen Taylor, unless otherwise noted

Most genealogists, working backward through family lines, tense up when they reach the 1840 census. Brows crease. Heartbeats quicken. Palms feel clammy. Why? Because most names have disappeared.

On this and earlier federal enumerations, entire households are reduced to tick marks or numbers in columns labeled with age ranges, sex and race (free white, slave or free “colored”). Only the head of the household—usually a man—is referred to by name.

This, of course, severely hampers your ability to pick your family out of the hundreds or thousands of similarly named folks: There are no names and clearly indicated ages of a wife or children to confirm that this, indeed, is the John Henderson household you’ve been looking for. And if it’s the wife or a child you’re trying to locate—well, you’ve got a hill to climb.

What’s a genealogist to do? First, take a deep breath and let it out. Slowly. Sure, those pre-1850 censuses are more difficult to figure out than their later counterparts, but they’re far from impossible. With our 11 steps, you can milk those tick marks to find your ancestors in early censuses. Two case studies at the end of the article will show some of this guidance in action.

1. Profile Your Family

The cardinal rule of genealogy is to work backward in time, and this strategy is essential when making the leap from the 1850 to the 1840 census, then 1830, and so on. You’ll translate 1850 census data on your family into the tick-mark “language” of the 1840 census, creating a profile you can compare to households that show up in your census search results. Here’s how.

First, you’ll need the 1850 and 1840 census worksheets. Once you’ve found your ancestors in the 1850 census, copy the names, ages and other information into the 1850 worksheet. Write the head of the household on the 1840 form. Next, subtract 10 from each household member’s age in 1850, including the head of the household, and mark the appropriate category in 1840. Use the same process to leap from the 1840 to 1830 census. You’ll find an example of how I did this for my Samuel Stockwell family here:

Estimating how your family looked during early, head-of-household-only censuses is essential to finding their record. Here’s how I profiled my Samuel Stockwell family for my 1840 census search.

Identify my family in the 1850 census

Samuel Stockwell, age 50, and his wife, Content, 46, live in Monroe, Franklin County, Mass. Their children Emery, 17, and Sarah, 14, were born in Vermont. Their other children—Mary, 11, Lucy, 9, and Ellen, 7—were born in Massachusetts.

Fill out an 1840 census tracker

Subtract 10 years from each person’s age. So I estimated the household to look like this:

- Free white males 5 and under 10: one (Emery)

- Free white males 40 and under 50: one (Samuel)

- Free white females under 5: two (Mary and Sarah)

- Free white females 40 and under 50: one (Content)

Start the 1840 census search

Because Mary was born in Massachusetts about 1839, I looked for the family there in 1840. I found a Samuel Stockwell household in Monroe that looked promising, but it did have some discrepancies. Here’s what the return shows:

- Free white males 5 and under 10: two

- Free white males 10 and under 15: one

- Free white males 40 and under 50: one

- Free white females under 5: two

- Free white female 15 and under 20: one

- Free white females 30 and under 39: one

The total number of family members in this listing is eight—six children and two adults. There’s an extra 5-to-9 year-old-boy, 10-to-14 year-old boy and 15-to-20 year-old girl.

Despite the extra individuals, I won’t automatically throw the match out the window: The family could have taken in nieces and nephews, or a child alive in 1840 might have succumbed to illness before 1850. An older offspring could have married and left home. I need to do some further digging into town and vital records for this Stockwell family in search of the identities of the other members of this household.

The census also indicates one of the eight is “insane or idiot at private charge.” It wasn’t necessarily a family member: In New England at the time, towns would pay families to take care of individuals in need of help.

Questions asked in each pre-1850 census

The age and gender categories used in early censuses got more detailed as time went on. Average life expectancy was 35 in 1790, and the government was most interested in voters and men of military service age, so censuses didn’t need many categories. But by 1830, Uncle Sam was counting centenarians.

When profiling your families for pre-1850 census searches, sort them into these categories. (Note that the 1820 census double-counted some young men: It had categories for men ages 16 to 18 and ages 16 to 26.)

Note that many collections relevant to genealogy research have suffered significant record loss. Early censuses are no exception. The 1790 and 1810 censuses, in particular, have been lost for many states and territories, with more-consistent coverage by the 1830 and 1840 counts. For more details, see the National Archives landing page for each census, or the FamilySearch Research Wiki’s pages for each state’s census.

Read enumerator instructions to better understand what was asked and how enumerators were to report data. The US Census Bureau has collected instructions for each census.

Lindsey Harner

Here’s a summary of what was asked in each census. Click the census heading for our dedicated research guide.

1790

- free white males of 16 and upwards, including heads of families

- free white males under 16

- free white females including heads of families

- all other free persons

- slaves

1800 and 1810

These censuses had categories for both free white males and free white females in these age ranges: under 10, 10 through 15, 16 through 25, 26 through 44, and 45 and over. Separate columns count all other free persons and slaves, with no age or gender breakdowns.

1820

For free white males and females, the 1820 census kept the same categories as in 1810, except for an added column breaking out free whites ages 16 to 18 (who were double-counted under those age 16 to 26).

Male and female slaves and free persons were counted in categories for those under 14, of 14 and under 26, of 26 and under 45, and 45 and upwards. A final column tallied “all other persons except Indians not taxed.”

For the first time, enumerators ventured beyond simply counting people. Respondents were asked about their professional industries and the naturalization status of immigrants in the household:

- Number of foreigners not naturalized

- Number of persons (including slaves) engaged in agriculture (farmers, for example)

- Number of persons (including slaves) engaged in commerce (storekeepers, for example)

- Number of persons (including slaves) engaged in manufactures (mill workers, for example)

1830

By Lindsey Harner

Officials printed schedules for marshals and enumerators to use, making the documents easier to read. The forms were expansive and required two pages to accommodate all the new information—make sure you scroll to the second pages in each entry to see all relevant data.

More age categories were once again added, now covering 5- or 10-year increments for white males and females. And the census denoted individuals who were deaf, dumb (i.e., unable to speak), or blind, and breaks this data into the following categories:

- White persons who are deaf and dumb, under 14 years of age

- White persons who are deaf and dumb, of the age of 14 and under 25

- White persons who are deaf and dumb, of age 25 and upwards

- White persons who are blind

- Slaves and colored persons who are deaf and dumb, under 14 years of age

- Slaves and colored persons who are deaf and dumb, of the age of 14 and under 25

- Slaves and colored persons who are deaf and dumb, of the age of 25 and upwards

- Slaves and colored persons who are blind

In 1830, census-takers no longer counted the number of people employed in different industries, but continued asking about foreigners not naturalized.

1840

By Lindsey Harner

Of the early censuses, the 1840 census delivers the most information. In addition to the previous demographic categories counting individuals in each household, census-takers were required to count the number of individuals employed in any of the following categories:

- Mining

- Agriculture

- Commerce

- Manufactures and trades

- Navigation of the ocean

- Navigation of canals, lakes and rivers

- Learned professional engineers

The census also marked pensioners for veterans of the Revolutionary War or other military service. Data in that column hints at service and pension records for the veteran, which may be found online at Ancestry.com, Fold3 and FamilySearch.

The 1840 census continued asking about individuals who were deaf, dumb and blind, but also individuals who were “insane” and “idiots.” (These were terms used at the time to denote individuals suffering from a mental illness or disability.) They were categorized by race, and noted alongside information about whether they were a public charge (e.g., being treated at a local facility) or a private charge (cared for at home, likely by family members).

The 1840 census also counted the number of free white persons over 20 years of age who cannot read and write. It omitted, however, the question about foreigners not naturalized.

Information was also collected about educational institutions, with tallies of students and the universities/colleges, academies/grammar schools, and primary/common schools themselves. A separate column counted students at public charge—in other words, students who were supported by government funds.

2. Be Flexible with Ages

Your profile might not exactly match the census, even if it’s the right family. That’s especially true for ages. Our ancestors weren’t as age-conscious as we are. Sometimes an ancestor’s age category from census to census will have stayed the same—or advanced 20 years—because he wasn’t sure of his exact year of birth. Pick out households that closely fit your family’s demographics, then eliminate them one by one as your continued genealogical research in other records rules them out.

Keep the census day in mind when calculating ages for your profile. It took months for enumerators to visit households. To keep things consistent, an official census day was established for each enumeration. All ages were to be recorded as of that day. Of course, enumerators occasionally deviated from this directive, but in general, a child born after the census day won’t be recorded in that census, even if he was two months old by the time the census taker made it to his parents’ home.

In 1790, the census day was Aug. 2; in 1800, Aug. 4; 1810, Aug. 6; 1820, Aug. 7; and in 1830 and 1840, June 1. See our list of all the official census days.

3. Search Smart

If you can, search pre-1850 census records on Ancestry.com, where the search forms for each census are customized to match the categories in that census.

For example, you can go to the 1820 census search form, enter the head-of-household’s name and where you think the family lived, then type in the numbers of “Free White Persons Under 16,” “Free White Persons of 16 and under 25,” “Free White Persons Over 25,” “Total Slaves,” and so forth in the household. Remember to include the head of the household in the numbers.

To find the search form for the census year you need, visit here, scroll down to the list of Included Data Collections and choose a census. If you don’t have an Ancestry.com subscription, see if your public library offers Ancestry Library Edition to patrons.

Early census records are on other websites, but without that helpful category search. Find them at FamilySearch and MyHeritage.

4. Check Name Variants

Just as you would for later censuses, search for variations of your ancestor’s name. A Joseph Henry might have gone by Henry or J. H., so check middle names and initials. The census taker or an indexer could have misinterpreted the name, leading to some strange spellings.

In Ancestry.com’s 1830 census collection, Agrippa Hull of Stockbridge, Mass., was indexed as Whippy Heel. If you find such a transcription error on Ancestry.com, you can click on “annotate this record” and add the correction. The correction will become searchable as an alternate transcription for the record, making the record easier for other researchers to find.

5. Understand Boundary Changes

You may find your ancestor living in an unexpected place, too. During the half-century from 1790 to 1849, territories became states and new counties were born. For instance, in 1820, Maine separated from Massachusetts to become its own state. As geographic boundaries changed, your ancestors’ state, county or city of residence could be different from census to census, even though they didn’t move.

You can trace these geographical changes using the Newberry Library’s Atlas of Historical County Boundaries. If you don’t find your ancestor by searching in his usual place of residence, try broadening your search to a neighboring county or state—or altogether eliminating a place from your search terms.

6. Put Families in Historical Context

By James M. Beidler

Likewise, constant pushing toward an ever-changing frontier characterized the time period covered by the head-of-household censuses. That means you’ll find families moving through multiple states, census by census.

You’ll also discover families listed in multiple counties in the same state—even if they never moved. That’s because state governments created new counties and subdivided old ones as population surged into new areas.

Finding an ancestor in a new county doesn’t necessarily mean he moved. Is the township name the same? Then your ancestor likely had the same residence he did 10 years before. Of course, townships splintered during this time period, too, so the township name could have changed. (See No. 5.) It’s common for different counties in a state to have townships bearing the same name—especially presidential ones such as Washington, Jefferson and Jackson. Every county seems to have one of those.

The Peter Daub family (see the case study below), enumerated in the 1820 census at their home in Jackson Township, Lebanon County, Pa., illustrates this concept. The family didn’t move between 1800 and 1820, but the 1800 census entry—found under the variant spelling Peter Toup—lists their residence as Heidelberg Township, Dauphin County, Pa. Both the county and the township changed in those 20 years between censuses (I haven’t found Peter in the 1810 census).

Almost all heads of household listed in the census were men. The few women listed as heads of household tended to be widows with property. In many cases, they’re listed simply as Widow Peters or Widow Smith. Younger widows, especially those with young children, typically remarried and remained anonymous tick marks on the census.

7. Take Extra Steps With Female Ancestors

If you’re searching for a woman, you might have a hard time: Unless she was the head of a household—say, she was widowed and lived on her own—she won’t be enumerated by name. Make a list of all the men in her life at the time and run searches for them: father, husband, sons, sons-in-law, brother, brothers-in-law, neighbors.

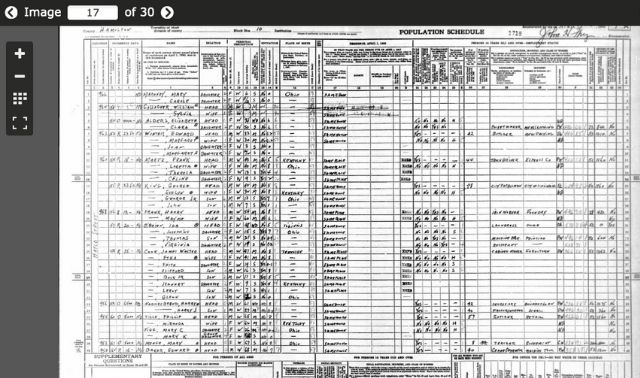

8. Make Copies of Early Censuses Easier to Read

In these early censuses, it’s easy to misread the tick marks in the columns. Until 1830, enumerators had no standardized forms. Instead, they would create their own. These handwritten sheets might lack lines dividing the rows of families, so the enumerator’s markings could appear to belong with a family above or below yours.

Try printing the return and penciling in your own dividing lines between rows of tick marks. Once you figure out which row is your family’s, mark it with a highlighter. Not all of the pre-1850 censuses include column titles, either—another reason our downloadable census forms are handy.

9. Look at Pages Forward and Back

It’s always a good idea to check at least one page previous and one page ahead of the census return listing your family so you can survey the people in the neighborhood. Households weren’t necessarily located in the order they’re listed—the enumerator might have gone back and forth across a street or up one side and down the other, or later gone back to houses where no one answered the first time. In some locations during the 1790 census, local residents came to the enumerator in a central location.

All this means your ancestors’ next-door neighbors—who may be family, too—could be listed on a different census page. Even if they’re not related, the names of neighbors can provide you with research clues during a time when social activity was usually limited to those who lived nearby. Because neighbors often served together in the military and vouched for each other in court documents, those names will help you identify your folks in probate, military and court records. And your kin might be named in records the neighbors left behind.

10. Find Census Substitutes

Early technologies and hard-to-cover terrain have led to gaps in early census records. For example, the 1790 census schedules for Delaware, Georgia, Kentucky and New Jersey are missing. Virginia’s 1800 census is lost and 1810 records are missing for 18 counties. The 1800 census for Tennessee is lost, too.

In some cases, genealogists have “re-created” missing census records using state enumerations and tax records. Also look for books such as The Reconstructed 1790 Census of Georgia: Substitutes for Georgia’s Lost 1790 by Marie De Lamar and Eisabeth Rothstein (Clearfield). Run a web search on the place and census substitute to find websites and books with these records. (See more information in No. 11.)

11. Use Other Records to Confirm Theories

By James M. Beidler

By now, you know that head-of-household censuses say frustratingly little about our ancestors. Still, they can be powerful tools when you use them in tandem with other records. How? Turn to these four common record types to start replacing those tick marks with names. Just remember: In genealogy, redundancy is a good thing. Try to find at least two records to confirm any hunches.

Tax lists

Our ancestors paid taxes every year, and many of the resulting records have survived. Tax lists typically note the amount of property a person owned along with a description of that property—animals, carriages and so on. Because these lists were prepared annually, they can tell you when individuals moved in between censuses. In some cases, tax lists even show where an individual went after leaving a particular township or county.

Vital records

Your best bets for getting information about late-1700s and early-1800s births, marriages and deaths (which predate statewide registration) are often church congregational registers. That is, unless you’re blessed with New England ancestors, in which case town registers of births, marriages and deaths will be a big help.

In any event, vital records should give birth dates, letting you attach names to those tick marks. In the case of Peter Daub’s family, I found that the birth dates listed in the baptism records of Peter’s children, as well as some of their burial records, matched the age-range groups in the census. This was important, since three different Peter Daubs lived in Lebanon County at the time.

Estate records

Many (but not all) people name their children in their wills, often in birth order. Compare that information with a census schedule for the corresponding family. Are all the children accounted for? Of course, sometimes it’s better if an ancestor died without a will: In that case—assuming there was an estate worth splitting—one of his children would have filed a petition naming all of the deceased person’s offspring. Wills and other estate records can help you learn the elusive first name of “Widow Smith,” as well.

Land documents

As we’ll discuss, the people listed above and below your ancestors aren’t necessarily neighbors. Well, records of land sales can reveal the real people next door. Registers of deeds contain descriptions of property being sold, including the names of people who owned land on all sides of a property.

12. Look for Other Clues

As discussed earlier, pre-1850 censuses are short on the details we appreciate in later enumerations. But they do contain clues, including:

- Occupations: In the 1820 census, enumerators noted how many in a household were engaged in occupations involving agriculture, manufacturing and commerce. More employment data came with the 1840 census, when enumerators counted those in mining; agriculture; commerce; manufacturing and trade; ocean navigation; canal, lake and river navigation; or the “learned professions.”

- Naturalization status: In 1820 and 1830, a column tells you how many in the household were “foreigners not naturalized.”

- Disabilities: The government began collecting social statistics with the 1830 census. You’ll see whether any white members of a household were blind or deaf and “dumb.” The 1840 census adds “insane” and “idiotic” to those categories.

- Education: Students in a household were counted in 1840, as were white males over age 21 who couldn’t read and write.

- Military service: The 1840 census lists names and ages of people collecting military pensions, even if they weren’t head of a household.

13. Guess at Relationships, Without Making Assumptions

By James M. Beidler

The names appearing close to your ancestors’ on pre-1850 censuses might signify neighbors—or they might not. Some schedules alphabetized the residents within a township or county. The names on unalphabetized lists might be worth looking into, but don’t assume they’re neighbors. Many census takers formed loops through their designated areas, which means they might not have gone to adjacent houses in the order you think they would have.

Although you can hypothesize relationships based on the census age ranges, remember your hypotheses could be false. Some households contained orphaned nephews, nieces and cousins; parents and fathers-and mothers-in-law; aunts and uncles; siblings and siblings-in-law; live-in servants; and hired day laborers who happened to be working on census day.

Take, for example, William Dill, enumerated in 1810 at his residence in Dover, Kent County, Del. His household comprised a male age 26 to 45, a male under 10, two females 26 to 45, one female 16 to 26 and two females under 10. The family could consist of William, his wife, a sister-in-law, an older daughter and three young children. Or William could be a father with two widowed daughters and four grandchildren. The possibilities are endless—but you can narrow them by consulting other records in conjunction with the census.

Don’t be intimidated by those pre-1850 censuses. Just take a deep breath, roll up your sleeves and start employing these 10 strategies. You may need a little more elbow grease, but finding your family will be worth the extra effort.

Case Study 1: Constructing a “Shadow Census” for the Daub Family

By James M. Beidler

If you need help translating those tick marks into real relatives, try constructing a “shadow census.” Here’s how.

Once you find a pre-1850 census enumeration for your family, create a chart with three columns. In the first column, write down the gender and age group of every person in the household, from oldest to youngest. Then calculate the likely birth year for each person; put those dates in the second column. Finally, use the third column to fill in any names and dates you’ve gleaned from other records that seem to fit the census entries.

Below, I’ve charted the household of Peter Daub, enumerated in the 1820 census.

| Census Entries | Estimated Birth Years | Possible People |

|---|---|---|

| male age 45+ | born by 1775 | Peter Daub, born about 1770 |

| female 26-45 | 1775-1794 | Magdalena (wife) |

| female 26-45 | 1775-1794 (sister-in-law) 1771 | ? Anna Maria Noll |

| male 16-26 | 1794-1804 | John (son), born 1797 |

| male 16-26 | 1794-1804 | Peter (son), born 1800 |

| female 16-26 | 1794-1804 | ? Magdalena (daughter-in-law) |

| male 16-18 | 1802-1804 | Johann Jacob (son), born 1805 |

| male 10-16 | 1804-1810 | Nicholas (son), born 1807 |

| female 10-16 | 1804-1810 (daughter) 1809 | Maria Magadalena |

| male under 10 | after 1810 | Johann Henrich (son), born 1813 |

Just as likely as not, you’ll find some “extra” people in the household. Use the genders and birth-year ranges of these individuals as clues to expand your search to extended family. From other records, I learned that head of household Peter Daub eventually became the administrator of his sister-in-law Anna Maria Noll’s estate. Anna Maria may have been widowed and moved in with her extended family. Son Peter Daub and his wife, Magdalena, were married in 1819; the newlyweds could have been living with his parents in 1820.

Case Study 2: Re-Creating the Higgins Household

By Lindsey Harner

My ancestor James R. Higgins was born in 1832 or 1833 and lived in Chester, Delaware County, Pa. He served in the Civil War and was killed at the Second Battle of Bull Run in 1862. The few records he left behind (including the 1860 census and his Civil War enlistment record) didn’t identify his parents.

Later censuses helped me find two women who were likely James’ sisters: Sarah Higgins and Hannah Dutton. But researching their parents resulted in a dead-end.

I’ll walk you through the five general steps I took to identify James and his possible family in the 1840 census.

Find the Right Household

I tried to find a workaround, starting with the 1840 census (the first taken after James’ birth). I found just one household named Higgins in Delaware County, headed by a man named Isaac. A 5- to 9-year-old boy lived there, and his age is consistent with James’ at the time.

Compare Across Censuses

That household seems to be the only Higgins family in the county for the 1820 and 1830 censuses as well.

The adults enumerated in those three censuses are as follows. (We’ll cover the children listed in the 1840 census later.)

1820 census:

- 1 white male, 18–25

- 1 white female, 16–25

- 1 white female, 26–44

1830 census:

- 1 white male, 30–39

- 1 white female, 30–39

1840 census:

- 1 white male, 40–49

- 1 white female 40–49

- 1 white female 50–59

Estimate Birth Years

Who are these people? The white male age 18–25 in 1820 and 40–49 in 1840 is almost certainly Isaac. The similarly-aged female is presumably his wife, Elizabeth; I found an 1817 marriage record between Isaac Higgins and an Elizabeth Evans. The older woman in the house could be Isaac’s mother, mother-in-law, sister or aunt.

In any census, you can estimate a person’s birth year by subtracting their age from the census year. For pre-1850 censuses (in which ages are presented as a range), you should do this for both the minimum and maximum age to generate possibilities.

Age categories differ between the 1820 and 1830/1840 censuses. With that in mind, I can home in on birth years for both Isaac and Elizabeth. I subtracted their minimum and maximum ages from the 1820 census year. That gave me a range: 1795 to 1804. I did the same for the 1830 and 1840 censuses, which generates a range of 1791 to 1800.

Assuming their age ranges were correctly recorded in all three censuses, the overlap (1795 to 1800) is our target for their birth years. That means they were the appropriate age to have children between 1829 and 1836, which is when James and his sisters were born.

Research Family Networks

At the Delaware County Archives, I found an estate administration record for Isaac, who died in 1841. Though he perished, I was able to research Elizabeth forward in time.

In the 1850 census, Elizabeth lived with a teenager named Phoebe Higgins, likely her daughter. Elizabeth applied for a War of 1812 widow’s pension, since Isaac was a veteran. In the application, an Ann Crump—perhaps another daughter—testified as Elizabeth’s caretaker. Crump’s household in the 1850 census revealed two sisters: Catherine and Sarah Higgins.

Based on all that work, I’d found two family networks of interest that I believed were related to Isaac Higgins:

- James and his sisters: James R. Higgins (b. 1832–1833), Hannah Dutton (b. 1829–1830), Sarah Higgins (b. 1835–1836)

- Elizabeth and her daughters: Elizabeth (b. 1795–1800), Ann Crump (b. 1820–1821), Sarah Higgins (b. 1833–1840), Phoebe Higgins (b. 1834–1837), Catherine Higgins (b. 1839)

Compare Households With Other Records

Put together, the two networks line up nicely with Isaac and Elizabeth’s household in the 1840 census.

1840 census of Isaac Higgins household | Expected 1850 census of Isaac Higgins household, based on age and sex | Possible family identities, with names and ages from 1850 census |

| 1 male age 40–49 | 1 male age 50–59 | Isaac Higgins (d. 1841) |

| 1 female age 40–49 | 1 female age 50–59 | Elizabeth Higgins (née Evans), age 50 |

| 1 female age 15–19 | 1 female age 25–29 | Ann Crump (neé Higgins), age 29 |

| 1 female age 10–14 | 1 female age 20–24 | Hannah Dutton (née Higgins), age 20 |

| 1 male age 5–9 | 1 male age 15–19 | James R. Higgins, age 19 (estimate) |

| 3 females under age 5 | 3 females under age 15 | – Sarah Higgins, age 16 (living with Ann Crump) – Phoebe Higgins, age 15 (living with Elizabeth Higgins) – Catherine Higgins, age 12 (living with Ann Crump) |

These early census records alone don’t prove a relationship between James, Isaac and Elizabeth. However, in combination with other documentary evidence, they provide an important piece of the puzzle to support the hypothesis that Isaac Higgins and Elizabeth Evans were James Higgins’s parents.

As possible next steps, I’d want to research the daughters. Can I find marriage records that establish Hannah Dutton and Ann Crump were both Higginses? That Sarah and Catherine lived with Ann Crump in the 1850 census certainly suggests a relationship.

Related Reads

Versions of this information appeared in the May/June 2012 (Taylor) and July/August 2024 (Harner) issues of Family Tree Magazine, as well as the 2006 Genealogy Guidebook (Beidler).

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program. It provides a means for this site to earn advertising fees, by advertising and linking to Amazon and affiliated websites.