Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

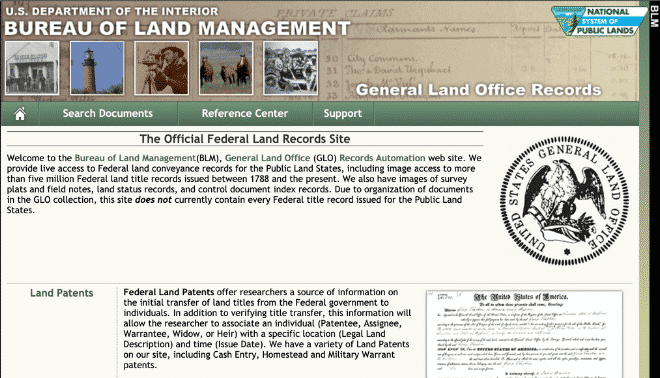

The Bureau of Land Management’s General Land Office website hosts over 5 million title records for US public-land sales. Through the 1862 Homestead Act, the federal government distributed 270 million acres of land across 30 states. About half of the recipient “homesteaders” successfully proved their claims, meaning they qualified to keep parcels of 160 acres each. Was your family part of this history? What records tell their stories?

Read on to learn how to search the BLM GLO website in four easy steps, or watch the video below for a tutorial.

1. Collect Your Information

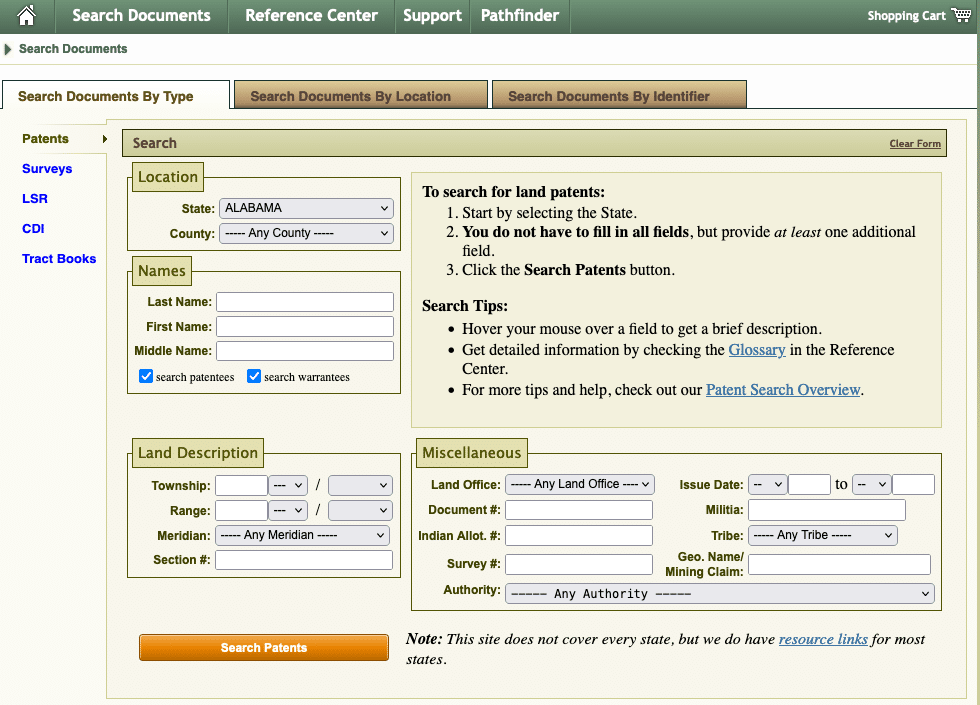

The website offers several kinds of records, each worth investigating. But you’ll likely want to start with a Land Patents search, especially if you have family who lived in one of the 30 public-land states during the distribution era.

Note: Land in the other 20 states—the original 13 colonies, plus four states that were later carved out from them and Texas, Vermont and Hawai’i—was distributed using different methods. Consult this download for a list of public-land versus state-land states.

From the Land Patents portal, you can enter a state and county name, plus the names of patent owners. If you already know about the land, you can also search by Land Description: township, range, section number, and so on.

Under Search Tips, you can access a glossary of some of the website’s terminology, plus (through Patent Search Overview) tips for using wildcard characters when you don’t know an exact spelling. You can also change your search to find different kinds of documents using the options at left.

2. Start Your Search by Surname

My ancestor Washington McClelland lived in “Nowhere,” Idaho, during this time period, so I’m going to look for him. He has an unusual surname, so a simple search with his surname and the state will hopefully do.

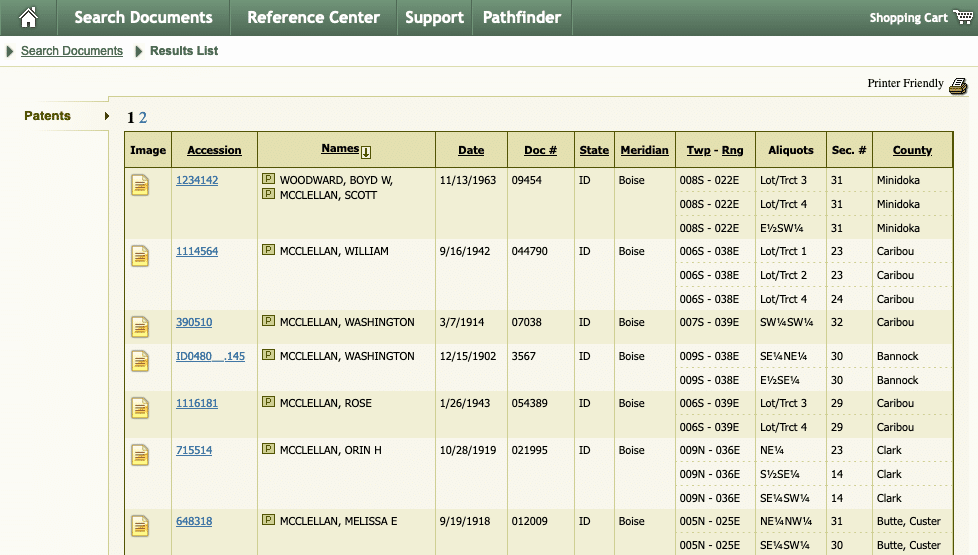

Unfortunately, the search system isn’t flexible, and a Washington McClelland didn’t show up in my results. I tried a spelling variant that I know he used later in life—McClellan—and was able to find claims from both him and his daughter. (Searching by surname is also helpful to find multiple members of the same family.)

I see two different claims from two different counties, one from 1902 and from 1914. I could go directly to the patent image (the yellow paper icon), but I want to see the full information first. Click the link in the second column to do so.

3. View Patent Details

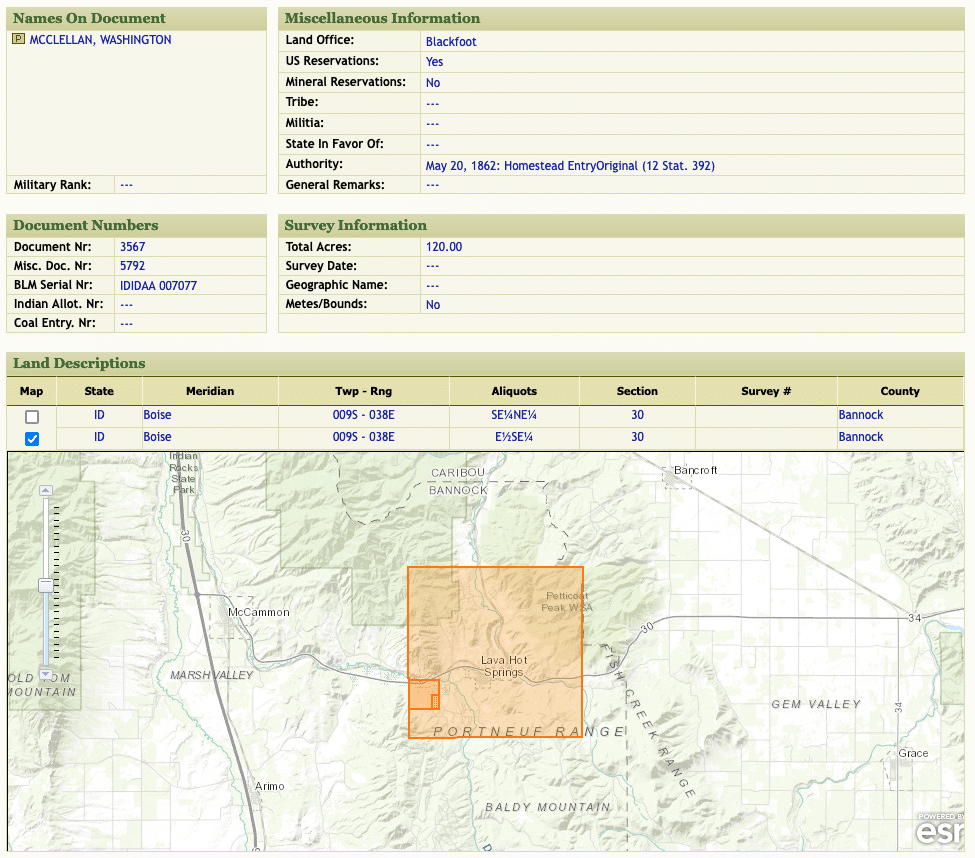

The Patent Details page has lots of information extracted from the patent, plus (critically) a map. Select the checkbox under Land Descriptions > Map to auto-zoom to the land parcel in question. Washington has two parcels listed; I’ve only mapped one here.

According to the map and the Township-Range, Aliquots, and Section values in the table, Washington owned the east half of the southeast quarter of section 30 in this township. (Again: Consult the GLO website’s glossary to learn what these terms mean.) This is indicated by the innermost highlighted area on the map.

You can also use mapping software to visualize the land. I’ve taken simple screenshots from the GLO website and placed them next to each other on a third-party map to see where family members’ claims were in relation to each other.

4. View Original Patents

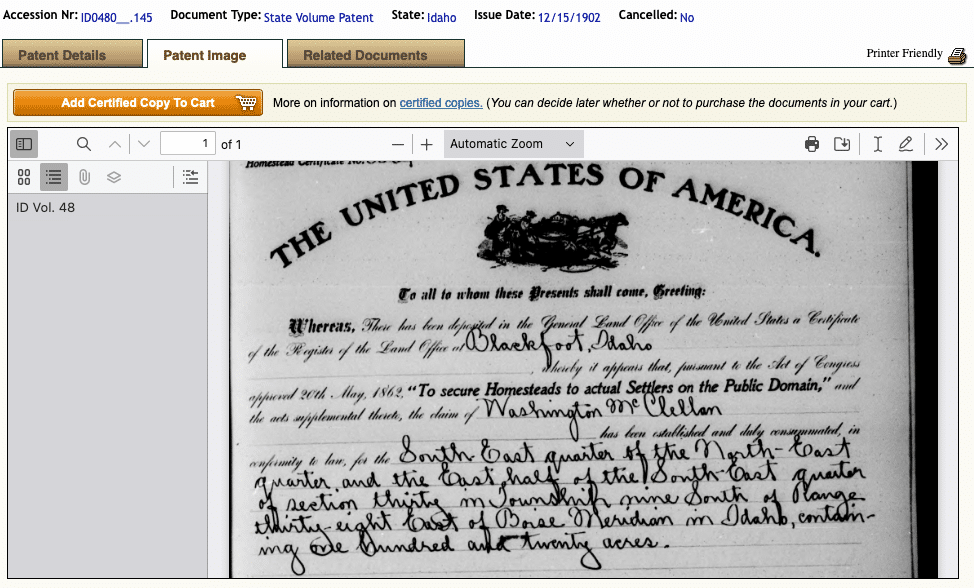

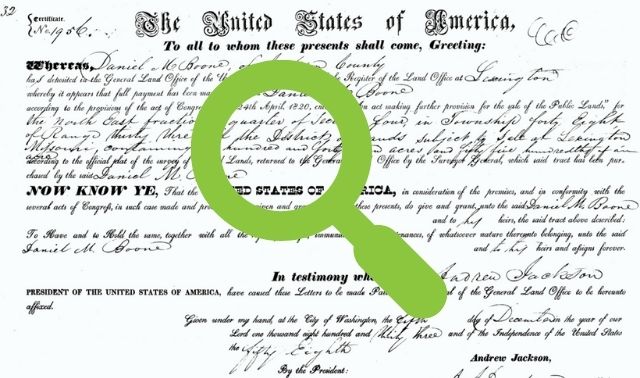

As previously stated, you can also view a digitized image of the original patent directly on the site.

In addition to Washington’s name, the patent spells out what two parcels of land he acquired: the southeast quarter of the northeast quarter, and the east half of the southeast quarter (which we mapped in step 3). Both parcels are in section 30 in township 9, south of range 38. The meridian was Boise.

You can download or print a copy of the patent. (Unless you have a specific legal need, you do not have to buy a certified copy.) There’s also a section for Related Documents, where you can see nearby land claims—some of whom could be owned by relatives.

Understanding Land Patents: The Rectangular Survey System, and What You Can Do With Them

Written by Nancy Hendrickson

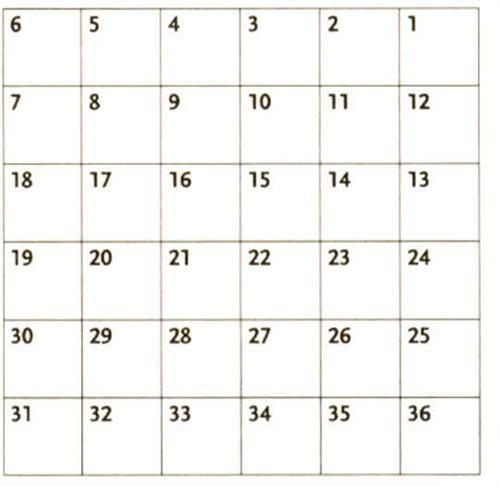

Public lands were surveyed using a rectangular system. Unlike the original 13 states, where property lines were often described in “metes and bounds” terms such as “10 paces from the black oak tree,” the rectangular system divided each township into 36 sections of one square mile each.

Sections were then divided into quarters or halves and named by their location within the section (a plot’s exact location is denoted by its “aliquot parts”). For example: the east half of the southwest quarter (“E ½ SW ¼”) of section 35.

How Townships Were Numbered

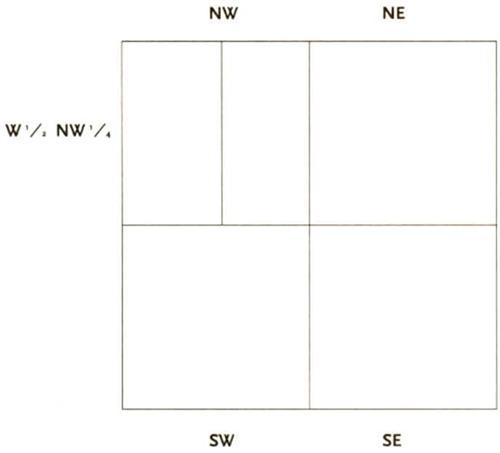

Division of a Section into Quarters

Exploring the Neighborhood

Once you’ve found your ancestor’s land patent, the search is over, right? Wrong. Now the real fun begins.

Remember how you’re always told in census research to write down the names of your ancestors’ neighbors? Those folks next door will likely show up later as in-laws, witnesses on wills or spouses.

The same principle holds true in land research. If you know who owned land around your ancestor, you’ll have more clues about your family. And you can use the search form to discover just who those owners were and where their land was.

Tip: Do a reverse search. Once you have the land’s aliquot parts, return to the search form and search by section, township, range and meridian. The results will include all people who purchased land in that section—your ancestor’s neighbors.

Becoming a map maker

It gets even better. Get a blank piece of paper and draw a square, then divide the square into quarters. Label the top right “NE,” the top left “NW,” the bottom right “SE” and the bottom left “SW.” Click on the land description for each person who owned land in that particular section, then divide each of the quarters you drew accordingly. You now have an accurate section map.

When you fill in your section map, be sure to write down the names of all the landowners. It’s like those census records — you never know what name is going to turn up in the family tree.

A version of this article by Sunny Jane Morton appeared in the March/April 2023 issue of Family Tree Magazine. The portions of this article by Nancy Hendrickson appeared in the October 2000 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Related Reads

ADVERTISEMENT