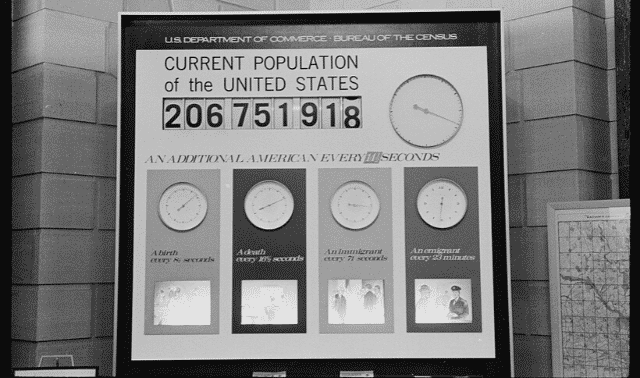

When it comes to counting American citizens, we’ve come a long way in the last 230 years. To help enumerate an estimated 310 million residents in the 2010 census, the Census Bureau expected nearly 3.8 million applicants—almost equal to the total US population in the first census in 1790—for 1.4 million temporary jobs.

Back in 1790, 650 federal marshals did the job over a span of 18 months, traveling house to house, unannounced, at a cost of $44,000. The marshals used sheets of paper or notebooks they designed themselves (the first centrally produced and printed forms wouldn’t be introduced until 1830). That inaugural count of 3.9 million Americans covered 13 states plus the districts of Maine, Vermont, Kentucky and the Southwest Territory (Tennessee).

Jump to: Which census years asked which genealogically important questions?

Enslaved African Americans were counted as three-fifths of a person, and American Indians (not subject to taxation( were skipped entirely.

Genealogists have Article 1, Section 2 of the US Constitution, adopted in 1787, to thank for one of the most valuable tools for tracing American ancestors:

“The actual Enumeration shall be made within three Years after the first Meeting of the Congress of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct.”

Given the tardiness with which many states got around to keeping vital statistics, the census is sometimes not only the best but the only official clue for birth dates and places of residence.

Better yet, access to US enumerations has never been easier. But the census is far from perfect. Besides the uncountable human errors made in providing and recording personal information:

- Indecipherable handwriting and flawed transcriptions plague all 15 available enumerations

- Not until 1850 did enumerators ask the names of others in each family besides the head of household.

- The 1890 census was largely lost to fire in 1921.

- Censuses after 1950 remain out of reach for privacy reasons.

- Sometimes your ancestors seem to have been skipped entirely, or to be hiding in places you haven’t thought to look.

But you can overcome many census hiccups with an understanding of the shifting decennial questionnaires and how to use the data they hold. The answers you’re after may take a little intuiting—or they may lurk in enumerations taken decades after your ancestor was dead.

Here’s a census-by-census look to get you started.

1790 Census Records

The nation’s first head count was as genealogically bare bones as could be: If you find an ancestral family in the 1790 census, the result will be nothing more than a name and a line of numbers. Enumerators recorded the name of the head of the family and the number of household members falling into each of these categories:

- free white males age 16 and older, including the head of household (to assess the fledgling country’s industrial and military potential)

- free white males under 16

- free white females of any age, all lumped together

- all other free persons (recorded by sex and color)

- slaves

Despite the minimal naming, the 1790 census (and other pre-1850 enumerations) still can be useful—especially if you transcribe the scanty returns onto a copy of the original form (download these census forms here). That’s because your printout of your ancestor’s original census record may not show headings for each column. And it’s helpful to have a version you can scribble on, trying to match those seemingly anonymous numbers with actual people.

Take Charles Seale’s simple 1790 census return from Camden District, SC, for example: 1-2-2-0-0. Although I can’t magically turn those numbers into names, I can match what I’ve learned from other sources about my fifth-great-grandfather’s family to confirm I’ve got the right census listing and figure out who each mark represents.

The 1 in the “males 16 and up” column must be Charles himself. The two boys under 16 match sons Joshua, about age 15, and Daniel, about 13. The next oldest sons, Elijah and James, would be at least 20—old enough to be off on their own. A little scrolling, in fact, finds Elijah and older brother Anthony in their own households on the same page.

The entry of two females must represent Charles’ wife, Lydia, and probably their daughter Charity, whose birth date I don’t know. Another daughter whose age I’m pretty sure would be about 25 in 1790, would likely be married and enumerated with her husband. I’ll hunt for Charity in the 1790 census under her husband’s name; if I can’t find such an entry, I’ll pencil in that she’s likely the youngest Seale daughter and living at home.

1800 and 1810 Census Records

The next two censuses, which used identical questionnaires, broke down the ages of household members in greater detail. For both free white males and free white females, these censuses counted those under age 10, 10 and under 16, 16 and under 26, 26 and under 45, and age 45 and up, as well as other free persons and slaves.

This breakdown is far more useful than the one in 1790, because it can help to separate parents from children (or grandparents living with their adult children and grandchildren) and it lets you match up the offspring more accurately.

For example, in Robert Dickinson’s (spelled “Dickison”) 1800 Moore County, NC, return, (0-2-1-0-1 for free white males; 0-1-0-0-1 for free white females), the male 45-plus is Robert himself, and the 45-plus female is wife Nancy (daughter of Charles Seale). The latter also helps confirm my birth date of about 1753 for Nancy. If you find, on the other hand, that there’s no one in the household of the right age and gender to be your ancestor’s wife, you might have a clue she’s died.

1820 Census Records

The 1820 census kept the same age/gender categories as the previous two except for an added column breaking out males ages 16 to 18 (who were double-counted under males age 16 to 26). This can really narrow a birth year if you happen to have a male ancestor born about 1802 to 1804. Just keep in mind that all age questions were supposed to be answered as of the date the enumeration began: Aug. 7, 1820. This census also asked for the number of “Foreigners not naturalized” and those engaged in agriculture, commerce and manufacture. Important for those with African-American ancestors, 1820 was the first census to distinguish between slaves and “free colored,” who were enumerated by gender and age (to age 14, 14 to 26, 26 to 45, and 45 and up).

1830 and 1840 Census Records

The 1830 enumeration—the first to use a standardized form—and the similar 1840 questionnaire broke down ages even more finely: under 5, 5 to 10, 10 to 15, 15 to 20, and every 10 years to the novel “Over 100.” (Ages were reported as of June 1 for both censuses.) A second page of the form records both slaves and “free colored” by gender and age: under 10, 10 to 24, 24 to 36, 36 to 55, 55 to 100, and 100 and up. There’s again a count of non-naturalized white foreigners.

New questions ask about persons who are deaf and dumb, separated by white, slaves and free colored; and by age (under 14, 14 to 25, and 25 and up). Blind household members also were counted, but weren’t differentiated.

The fine breakdown of ages can help narrow an ancestor’s birth year or make sure you’ve got the right match. In 1830 Wilcox, Ala., for example, my third-great-grandfather William Chapman appears as age 30 to 40—a perfect fit for the 1796 birth date I have for him. The female age 20 to 30 must be his wife, Mary (born in 1802). The two boys under age 5 fit sons Alpheus (born in 1827) and George (born in 1829).

If I knew the children’s birth order but didn’t already have dates for them, I could at least pencil in “1825 to 1830” as probable birth years for each. The female age 5 to 10 would be my great-great-grandmother Cornelia (born 1823). But who’s the extra male, age 20 to 30? That’s a mystery to solve—one of Mary’s brothers, maybe?—and a potential future clue.

Don’t freak out, however, if these early date ranges don’t always match: William Chapman is listed next door to his mother-in-law, “Mrs. Mary Clough,” whose age is given as 50 to 60. Obviously this is the right woman. Is my 1766 birth date for her wrong? As we’ll see in the 1850 census, either she fibbed about her age or the enumerator slipped up. In any case, because Mary’s a widow, I can pencil in her husband’s death date as before 1830.

1850 and 1860 Census Records

Genealogists might think of this as the “hallelujah!” census. Not only was each free person in the household finally listed by name, but specific ages (as of June 1) replaced those frustrating ranges. Each person was asked for birthplace (state or territory).

Other questions covered sex, color, occupation, value of real estate, whether married within the year, attending school within the year, illiteracy, and whether “deaf & dumb, blind, insane, idiot, pauper or convict.” This was also the first census to have separate schedules for slaves and for people who’d died in the year prior to the census (called mortality schedules; they also exist for the 1860, 1870 and 1880 censuses).

Answers abound in the 1850 census, some of them reaching back to resolve mysteries from earlier enumerations. Here’s Mary Clough, living with her daughter in Ouachita County, Ark., of all places, age 84, born in North Carolina. So not only is my 1766 birth date vindicated, but I can now start looking for Mary’s elusive parents in North Carolina. The 1850 census has given me clues to an event more than 80 years earlier.

The 1860 census questions were essentially the same as a decade before. It’s notable especially for Southern ancestors, as the last census before the disruptions of the Civil War, and it of course included the last slave schedule.

Don’t overlook this mortality schedule, which can offer further backward glances: My third-great-grandfather Michael Dickinson had gone missing from the census since 1830 (and even that listing might be another Michael Dickinson), including the vital 1850 enumeration. And he died in May 1860, just before the second census that recorded ages and birthplaces. But I found him in the mortality schedule, finally giving me his birth year of about 1776 in North Carolina.

1870 Census Records

This was the first census to count all individuals as “whole persons,” the Fourteenth Amendment having abolished the three-fifths counting rule in 1868. Similar to the 1850 and 1860 questionnaires, the 1870 census again included age (as of June 1) and birthplace. For the first time, it asked yes-or-no questions about whether each person’s parents were foreign-born. Don’t overlook this column if you’re trying to identify the offspring of early 1800s US immigrants.

Another two easily missed columns ask for the month of birth for babies born within the year, and for the month of marriage for couples wed within the year. If you have an ancestor born or married in the latter half of 1869 or the first half of 1870, here’s a little genealogical bonus.

1880 Census Records

Happily for genealogists, the 1880 census continued this interest in “nativity.” Besides asking the individual’s birthplace, questions also asked the birthplaces of the person’s father and mother.

Here again, the 1880 enumeration lets you reach back in time, providing answers that were missing from earlier forms. For instance, I can’t find my third-great-grandmother Amy Uptegrove on any census because she died young—before that breakthrough 1850 census. But from her son John Ashley Stowe’s 1880 census return, I learn she was born in North Carolina.

The 1880 questionnaire also added the genealogically important question of each person’s relationship to the head of household. You might assume that everybody in the family is a spouse, son or daughter of the head of household, but often nieces, nephews, grandparents and other kin moved in with relatives. Thanks to the 1880 questionnaire, you can figure out who’s who.

Similarly and perhaps surprisingly, 1880 was the first census to specifically ask marital status, with columns for single, married, widowed and divorced. It also asked whether married within the census year, but not for the month.

If you have American Indian ancestors, note that the 1880 census included a supplementary schedule with details on Indians living on reservations (although they didn’t count toward congressional apportionment until 1940). This was also the first census to employ professional enumerators rather than US marshals and their assistants.

1890 Census Records

Lost to fire except for fragments, the 1890 forms adopted a dramatically different, vertical look and added questions about how long a person had lived in the United States and his or her naturalization status. (As in subsequent years, Na is short for naturalized.) This enumeration also included the column “mother of how many children” and how many of those children were living. The 1890 census included a veterans schedule for enumerating Union veterans of the Civil War (although some Confederates were also counted) and their widows; about half of these schedules survived and can substitute for the lost census if you’re lucky enough to have a Union soldier in the family.

1900 Census Records

The census returned to its familiar horizontal orientation, and for the first and only time among available censuses, asked adults for their month and year of birth. If an ancestor was recorded in 1900, you can finally resolve those nagging questions from other censuses about approximated ages. The 1900 forms added a question about number of years married and was the first census to ask about home ownership—owned or rented, and owned free or mortgaged.

Another 1900 first: Enumerators asked for the year a person immigrated to the United States. Given the loss of the 1890 returns, with their question about how long a person had been in the country, 1900 represents your earliest opportunity to let the census nail down that elusive “crossing the pond” year. Armed with this fact, you can narrow your passenger records search.

My great-grandfather Gustaf Fryxell’s 1900 listing, for instance, shows that he and his parents were all born in Sweden, and that he arrived in America in 1876. His wife Hannah (“Anna”) was likewise born in Sweden, but I can figure out from the census that they tied the knot in the United States: They’d been married for 18 years, yet Hannah immigrated in 1881, 19 years ago. Those dates also tell me I need to look beyond Ellis Island, which opened in 1892, for passenger records.

1910 Census Records

The census took a step backward, genealogically speaking, in 1910, losing the question about a person’s month and year of birth because most states kept vital records by this time. It again asked for the year of immigration, a useful double-check on the previous census. (Sometimes it’s a lesson not to believe everything you see on a census return: By 1910, Gustaf Fryxell had either forgotten when he immigrated or someone answered erroneously for him, as this time, that column says 1880.) The redundant “years in US” question was dropped. For the first time, enumerators were supposed to ask about the mother tongue of foreign-born people, squeezing in an abbreviation for the answer next to the person’s native country.

Don’t overlook column 30 at the far right side of the form. All males over age 50 who were born in the United States or who immigrated before 1865 were asked whether they were “a survivor of the Union or Confederate Army or Navy.” UA means Union Army, UN is for Union Navy, CA for Confederate Army and CN for Confederate Navy. If your ancestor answered that he served in the Union forces, look for him in the 1890 veterans schedules.

1920 Census Records

The 1920 form closely followed 1910’s (and now Great-grandpa Gustaf was back to his original 1876 immigration date), with an additional question about a year of naturalization. (Don’t get too excited about this new question, however: Gustaf’s naturalization date, for one, is listed simply as Un—unknown.) “Mother tongue” got its own column for each person, and for each person’s mother and father—no more squeezed-in squiggles. But “number of years married” was dropped from the form.

1930 Census Records

The 1930 census had the largest form yet, measuring 23¾x16½ inches, with several new questions of genealogical interest. “Age at first marriage” now followed “Marital condition.” Two questions asked about a person’s veteran status: whether a veteran and, if so, “what war or expedition.” The year of naturalization was dropped—perhaps there were too many Uns 10 years before.

This was also the first census to inquire whether the household had a “radio set.” In another sign of the times, the standard population schedule was supplemented by a special “Census of Unemployment” (unfortunately, officials destroyed these schedules after collecting the data). There was also a short supplemental Indian schedule in 1930.

1940 Census Records

Written by Andrew Koch

Genealogy clues abound in the 1940 census. In the aftermath of the Great Depression (and in anticipation of the looming World War II), a whopping 14 questions were related to employment status, income and recent involvement in “public emergency work” (e.g., the Works Progress Administration).

In a first for the US census, some questions were asked only of a subset of respondents: parents’ birthplaces, native language, military service, occupation/industry, marriage information, and details related to Social Security.

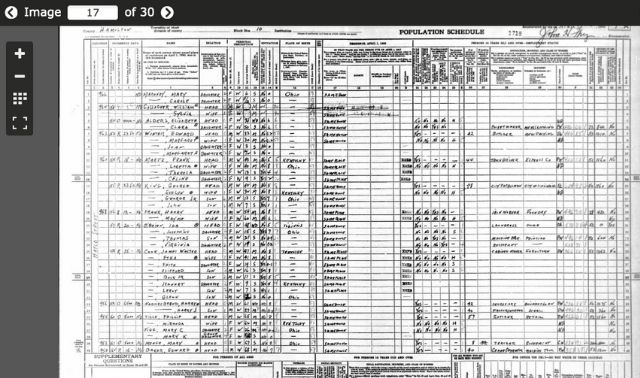

1950 Census Records

Written by Andrew Koch

Enumerators scaled back the number of questions asked in the 1950 census (released to the public in 2022). Many questions of genealogical value were moved to an expanded survey section and posed to just a random 20 percent of the population: previous residence, education, employment, income, and military service. An even smaller sample was asked about number of times married, number of children borne, and kind of work/business and industry.

Which censuses asked which genealogically important questions?

Name

- Head of household only: 1790–1840

- Everyone in the household: from 1850 on (except for slaves, 1850 & 1860)

Birth date and place

- Age range of free white males (ranges differ): 1790–1840

- Age range of free white females (ranges differ): 1800–1840

- Age of everyone in the household: 1850 on

- Birthplace: 1850 on

- Born within the census year (including month): 1870–1880

- Month and year of birth: 1900

Parents

- Foreign-born parents: 1870

- Parents’ place of birth: 1880–1930, 1940 & 1950 (sample only)

- Mother tongue: 1910, 1940 & 1950 (sample only)

- Self and parents’ mother tongue: 1920, 1930

Marriage

- Married within the census year: 1850–1890 (1870 includes the month)

- Marital status: 1880 on

- Number of years married: 1900–1910, 1950 (as “Years since [marital status change] occurred”)

- Age at first marriage: 1930, 1940 (sample only)

Immigration and citizenship

- Number of aliens/persons not naturalized: 1820–1840

- Year of immigration to US: 1900–1930

- Number of years in the United States: 1890–1900

- Naturalization status: 1890–1950

Education/Occupation

- Occupation: 1840 on

- Attended school in past year: 1840–1940, 1950 (sample only)

- Can read or write: 1850–1930

- Income: 1940, 1950 (sample only)

Other

- Number of free colored: 1820–1840

- Relationship to head of household: 1880 on

- Veteran status: 1890, 1910 (Civil War only), 1930, 1940 & 1950 (sample only)

- Mother of how many children/number living: 1890, 1900, 1910, 1940 & 1950 (sample only)

- Able to speak English: 1900–1930

Census Search Dos and Don’ts

Mind these tips for more-effective searching of online census databases:

Do:

- experiment with the site’s search tools, entering different search parameters and spellings.

- look for search tips to see whether you can use tools such as wildcard symbols or Boolean searching to catch mistranscriptions and unexpected spellings.

- try searching without a name—enter other information such as the person’s place of residence, birth date and immigration date.

- search for friends and neighbors your ancestor may have been living with.

Don’t:

- expect to find an ancestor on the first try. Assume the site’s data match everything you understand to be true about your family. Names may be spelled differently, for example, or people may have reported different ages or immigration dates from what you’ve found in other sources.

- assume it’s your ancestor because the name is right. Multiple people could’ve had the same name.

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the March 2010 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated in September 2022 to reflect the 1940 and 1950 censuses.