Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Way back in 2005, Family Tree published its first two US state guides. “These guides are designed so you can easily whip them out in your genealogy workspace, or take them with you on research trips,” wrote then-editor Allison Stacy. “Eventually, you’ll have a collection of tips and tools to trace your roots anywhere in the United States.”

Indeed, most issues since then have featured two state guides—they’ve proven so popular with readers that we come back to them again and again. Our May/June 2025 issue commemorated the completion of our third set of US research guides—this time, with all-new text written by a host of genealogy experts.

That milestone invites us to take a step back and revisit how to research your US ancestors—no matter what state(s) they lived in. The following whirlwind, birds-eye view (perhaps eagles-eye view?) will help you whether your family is made up of multi-generational residents or you’re researching in a brand-new-to-you state.

US History for Genealogists

Pre-1600s: Indigenous roots

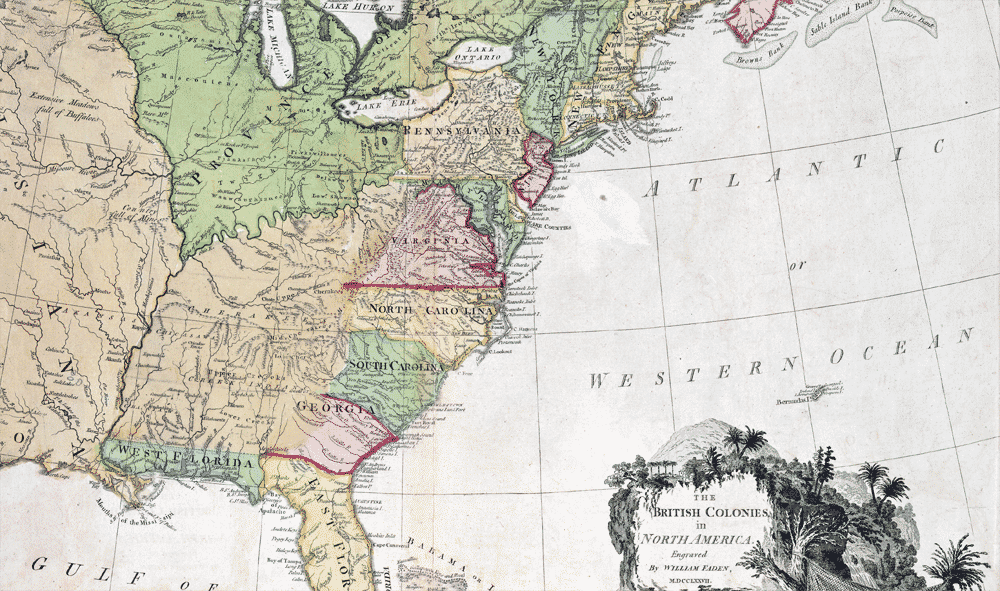

The United States as a sovereign nation traces its lineage to the Thirteen Colonies of Great Britain along the eastern seaboard. Although we recognize the country’s birthday as 1776 (and celebrate it turning 250 years old next summer), US history started long before that.

Indigenous groups have lived in what is now the United States for thousands of years. Relatively little is known about these civilizations, though archeology suggests some communities thrived in North America as early as 30,000 years ago. They developed large trade networks, diverse languages, and rich religious traditions.

Contact with Europeans (traditionally taught as beginning with Christopher Columbus’ arrival in the Caribbean in 1492) ushered in a long period of disease, displacement and relocation, assimilation, and violence. Estimates of Pre-Columbian peoples in the United States range from 2 to 12 million, and the population dwindled even by the time serious colonization efforts began.

1600s–1700s: Colonial America

It wasn’t until the 16th century that Europeans ventured into the North American mainland. Spaniards were active in Florida and the Southwest, founding St. Augustine and Santa Fe in 1565 and 1605, respectively. Meanwhile, the French set up fur-trade networks in the Mississippi and Ohio River Valleys.

The English arrived later, founding Jamestown, Va., in 1607 and disembarking from the Mayflower in Plymouth, Mass., in 1620. Puritans and other religious outcasts were drawn to New England (Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Rhode Island) in the early and mid-1600s. But it was fertile land that attracted farmers and private companies to venture into Virginia.

After establishing those two footholds, the English connected their northern and southern colonies in 1664 by absorbing Dutch settlements in the Mid-Atlantic (modern New York, New Jersey and Delaware). Additional charters formed the basis of the Carolinas, Maryland, Pennsylvania and (later) Georgia.

Colonial America was largely rural, with notable settlements in coastal cities such as New York, Philadelphia, Boston, Baltimore and Charleston. Most immigrants to Colonial America were subjects of the British Isles, and the first enslaved Africans arrived in 1619.

After the French and Indian War in 1763, Britain annexed all of France’s land claims east of the Mississippi River—and forbid its colonists from settling west of the Appalachians. Discontent over this policy (along with issues of taxation and representation in government) led the Thirteen Colonies to rebel against Great Britain. The new United States secured its independence in 1783.

1700s–1800s: The early republic

Settlers began flowing west, first through the Appalachian Mountains, then to the Mississippi River. The Northwest Territory (chartered in 1787) spurred migration to and through the Great Lakes. New states—Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi and Alabama—were carved out from the original Thirteen Colonies, and Vermont joined the Union after a brief independence.

Expansion continued. The Louisiana Purchase (1803) nearly doubled the size of the United States. And the War of 1812 demonstrated the young republic’s ability to stave off threats from the United Kingdom in the north and Spain in the south. The U.S. annexed Florida from Spain in 1819 and successfully negotiated the US-Canada border with the U.K.

The advent of riverboats and canals made travel through river valleys faster and more accessible. Cities such as Chicago, Cincinnati, Louisville, St. Louis and New Orleans grew in size and importance as settlers moved west.

Americans clashed with indigenous groups along these new frontiers. Harsh “Indian removal” policies forced Native groups from their ancestral homes in the Ohio Valley and Southeast to the Indian Territory of Oklahoma, either through land cessions or forced marches like the Trail of Tears (beginning in 1830). As would become commonplace throughout the 19th century, the US government opened land to white settlement after tribes were removed or had surrendered their land claims through treaties.

1800s: Expansion and division

Pursuing a policy of “Manifest Destiny,” the United States turned its eye westward to the Pacific Ocean.

The US annexation of Texas (1845) resulted in the Mexican-American War. The subsequent Mexican Cession add 520,000 square miles—and thousands of Spanish-speakers living in the Southwest—to the United States. An 1846 treaty with the United Kingdom secured US ownership of the coveted “Oregon Country” in the Pacific Northwest, which (along with California) drew migrants from across the country.

The newly acquired territory’s arid climate and mountainous terrain made it hard to navigate. But gold and silver rushes throughout the Mountain West drew fortune-seekers, whose journeys were aided by railroads and the blazing of migration routes (such as the famed Oregon and Mormon Trails). The purchase of Alaska in 1867 proved prescient, as a gold rush in the late 19th century drew tens of thousands.

The question of whether the “peculiar institution” of slavery would follow American settlers west dogged the country for decades and exacerbated economic and cultural differences between North and South. Congress attempted to maintain a balance of free and slave states through a series of compromises. The ill-fated Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854), for example, let settlers decide for themselves whether slavery would be permitted in newly organized territories.

Despite these efforts, tensions boiled over in 1861 when 11 Southern states seceded to form the Confederate States of America. More than 3 million Americans served on either side of the Civil War that raged for four years, displaced thousands, and left widespread destruction in the South. Confederate defeat ended the practice of slavery, but not African Americans’ struggle for civil rights.

Political unrest and economic hardship in Europe urged emigrants to come to the United States. By the late 19th century, the locus of immigration shifted from England, Scotland and Scandinavia to Germany, Ireland, Italy and Poland.

Migrants poured into the United States through ports such as New York’s Castle Garden (1855–1890) and Ellis Island (1892–1924). Victory in the Spanish-American War (1898) added Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines to the United States—bolstering the country’s Spanish-speaking population—and the U.S. annexed Hawaii that same year.

The 20th century and beyond

Differences in religion (many newly arrived immigrants were Catholic) and language triggered a backlash. These—and US involvement in the bloody World War I—stoked a culture of isolationism. In the early 1920s, Congress adopted restrictive immigration quotas and changed who was eligible for citizenship. Immigrants from China were barred from entry altogether from 1882 to 1943, and those from nearly all of Asia from 1917.

The Wall Street stock market crash of 1929 set in motion the worldwide Great Depression. Prospects were made worse by the “Dust Bowl” drought conditions in the Midwest.

But the US economy rebounded upon the country’s entry into World War II, which put millions to work through manufacturing, military service, and public-works projects. Victory over the Axis Powers cemented the United States’ status as a military, financial and industrial world power.

Economic prosperity and technological advancements raised Americans’ standard of living throughout the mid- and late 20th century. All the while, women and racial minorities secured larger, more-equitable roles in society. Women gained the right to vote in 1919, and the civil rights movement of the 1960s ended institutionalized segregation (epitomized by “Jim Crow” laws) against African Americans.

Congressional acts in 1952 and 1965 abolished the ‘20s-era immigrant quotas, allowing entry to the U.S. from a wider variety of countries. Arrivals from Asia soared, as did immigrants from Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean.

Through it all, Americans have been fascinated by their family history. With the rise of the internet, it’s never been easier to feel connected to the generations that have come before them.

US Birth, Marriage and Death Records

Unlike in some other countries, civil records of birth, marriage and death in the United States are kept by individual states, not the central government. As a result, there’s a patchwork of vital-registration start dates and access laws that affect what records were created and whether you’ll be able to view them.

Vital record coverage

In general, most states didn’t require vital records until the early 20th century. In 1919, Georgia and New Mexico became the last two states to adopt civil registration. Even then, some locales failed to comply for several years. And many larger cities kept records sooner, as did towns in New England and religious organizations.

Birth and death certificates from the past century or so tend to be restricted by privacy laws and held by state departments of health. Genealogists may be able to request limited informational copies, but some states restrict access to direct descendants of the person mentioned in the record. Older records are considered public and usually held by the state archive. Read our guides to birth and death records.

Marriage records were kept earlier by religious or civil authorities—often, from a county’s founding. The church or county courthouse created the original record, then (once required) sent a copy to state authorities. Access laws for marriage records are generally looser than for birth and death records, and many states offer indexes.

You’ll also often find a variety of marriage records besides the license or certificate: bonds, banns, and so on. These were dictated by laws, religious or cultural customs, or the norms of the time.

Accessing vital records

Vital records from around the country have been microfilmed and digitized thanks to partnerships between state and county archives, the FamilySearch Library, and large genealogy websites including Ancestry.com and MyHeritage. Some states maintain their own publicly-accessible collection of vital records; coverage varies greatly.

For help requesting records from an archive or state vital records office (usually for a small fee), see the National Center for Health Statistics’ “Where to Write for Vital Records” or the paid service VitalChek. You may also find vital records or indexes of them (especially of early communities) published in book form.

US Census Records

The U.S. Constitution tasks the federal government with taking a nationwide census every 10 years. That regularity makes census records (specifically, census population schedules) crucial for family history. Learn more from our guide.

Details in census records

That said, the first census, taken in 1790, was hardly a genealogical goldmine. It named only the head-of-household (usually a white man), relegating other family members to inventories of age, race and gender. Census forms lacked uniformity until 1830 and were handwritten, making them somewhat difficult to parse.

Questions greatly expanded beginning in 1850, eventually covering a broad range of topics: age, birthplace, occupation, level of education, and more. You can expect to find women named for the first time in the 1850 census and African Americans who were once enslaved in the 1870 census. (Most Native Americans were excluded from federal counts until 1890. Some tribes were counted in an 1880 “Special Census of Indians.”)

From 1850 to 1900, census officials collected additional statistical information. These “nonpopulation” schedules can be useful in certain circumstances. Learn more here.

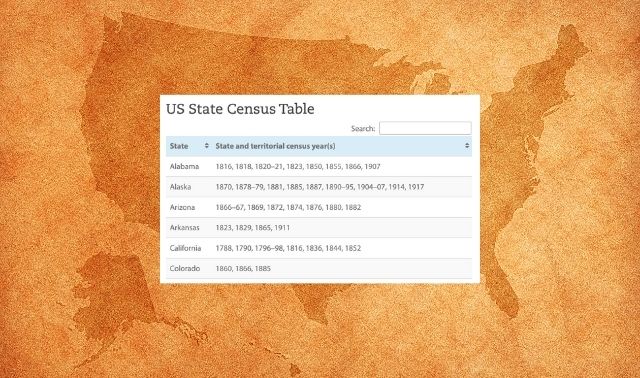

Many states took their own enumerations, too, including on the “fives” (1855, 1865, etc.) between federal counts. Some even took censuses in colonial times—you can learn more about state, territorial and colonial censuses here.

Accessing censuses

A 72-year privacy law restricts more-recent census records. As of this writing, the 1950 census is the latest that’s accessible to genealogists.

You can find census records widely on websites such as Ancestry.com, FamilySearch and MyHeritage. Originals are held by the National Archives, though they’re no longer available for in-person searching.

Note that records of early censuses have been lost for some places, and that pioneer residents may appear in censuses of their “mother states” of differently named territories. In addition: 1890 census records have been lost for most of the country. (Learn about workarounds here.)

US Immigration Records

Called a “nation of immigrants” and a “melting pot,” the United States has citizens whose ancestors came from all over the world. The years 1820 to 1924, in particular, are sometimes called a century of immigration, in which some 33 million people arrived on US shores.

1600s–Late 1800s

Early immigrants may or may not have been documented upon their arrival. Some are mentioned in published sources such as Passenger and Immigration Lists Index, 1500s–1900s by P. William Filby and Mary K. Meyer (Gale Research), available at Ancestry.com.

Passenger arrival lists were first required by Congress in 1820. Initially called “customs lists,” these were meant to inventory cargo and goods—not necessarily people. Still, they name each passenger and signify age, sex, occupation, date of arrival, and port of departure. Some ports (notably Boston, New Orleans and Philadelphia) kept passenger lists earlier than this.

Late 1800s to present

Standardized, more-detailed passenger manifests debuted in 1893, when the United States federalized immigration. By law, lists from that year forward had to include:

- Full name, age, sex, marital status and occupation of each passenger

- Each passenger’s nationality and place of last residence

- The passenger’s final destination in the U.S. and whether they were joining a relative, plus (if so) the relative’s name and address

- Name of the vessel

- Ports of arrival and departure

- Date of arrival

Accessing immigration records

The National Archives hold most surviving immigration papers. As with census records, NARA has made many of these valuable records available through partner websites.

Find passenger lists from New York City’s Ellis Island and its predecessor, Castle Garden, for free through the website of the Statue of Liberty—Ellis Island Foundation. NARA also has custody of records from other ports, notably Baltimore, Boston, New Orleans and Philadelphia.

Note that, when studying immigrant ancestors, you’ll need to dig deeper than their country of origin. Try to determine a specific county, parish or town name. That detail will help you not only find records in the old country, but also allow you to trace whole communities. (Many towns immigrated together.)

Immigrants may have arrived to the United States multiple times. Some “birds of passage” arrived in the United States, worked for a time, then returned to their home country at least temporarily.

US Land Records

Many immigrants were attracted to the United States for its vast, affordable land. Records of land transactions—though harder to find and understand than other documents—can thus provide important details about their lives.

Your ancestor’s purchase or sale of land may have generated a variety of records depending on the circumstances. But in general, land records come in two varieties: patents (in which the government sells land to an individual) and deeds (in which an individual sells land to another).

Public-land patents

In 30 of the 50 states, the federal government claimed initial ownership of land, then sold it to qualifying individuals. These include all states west of the Mississippi (except Hawaii and Texas), plus Alabama, Florida, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Mississippi and parts of Ohio.

Public land was surveyed using the rectangular survey system, which defined a series of standardized meridians (north-south lines) and baselines (east-west lines) and described land parcels in relation to them as part of a grid. When properly understood, the method made it easy to determine specific land boundaries.

Since 1788, the government has distributed more than 1 billion acres through 5 million patents and a handful of programs, notably:

- Homesteads: The Homestead Acts of 1862 granted up to 160 acres to adult citizens willing to live on and improve a piece of land for at least five years. From 1862 to 1976, homesteaders claimed 270 million acres, roughly equivalent to 10% of the United States’ total area.

- Bounty land: Veterans who served under certain circumstances were eligible to receive land for free as compensation. (Military bounties were also awarded in some state-land states; see the next section.)

- Railroad grants: Rail companies may have been eligible to receive a certain amount of land per mile of track laid. They generally either developed the land themselves or resold it to speculators.

Find federal land patents through the Bureau of Land Management’s General Land Office site. There, you’ll also find survey plats, tract books and more.

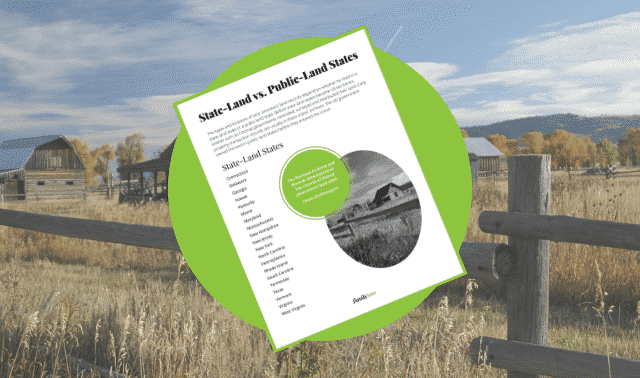

State-land patents

In the 20 state-land states, the state or colonial governments (not the federal government) sold land to eligible residents. These are the Thirteen Colonies, four of the states that were created from them (Kentucky, Maine, Tennessee and West Virginia), and the three states that were once independent republics (Hawaii, Texas and Vermont).

Unlike in public-land states, land in state-land states was traditionally surveyed using “metes and bounds.” That is, land was described in relation to nearby landmarks. Though imprecise and error-prone, this method defined boundaries in a manner that could be easily understood “on the ground.”

To find land-grant records, you’ll need to know which government was in power when your ancestor purchased their land. This may have been the British Crown; a colonial, territorial, or state government; or even the Spanish or French.

Deeds

Any subsequent land transactions occurred between private individuals and were documented by local authorities, usually a county recorder’s office. These sales generated deeds, which (though containing heady jargon) were often templated.

Deeds were not maintained in one central place like vital records or census records. Rather, the individual county recorder’s office might have destroyed them or handed them off to a state archive. The FamilySearch Library holds many local deeds, some have been indexed or made available through the site’s full-text search.

5 Questions when Studying a New State

In this article, we’ve focused on how to find US ancestors regardless of what state they lived in. But given the complexities of US history, researching in different states can sometimes feel like researching in entirely different countries.

Here are five questions to ask yourself as you look for ancestors in a new-to-you state. These are adapted from a presentation I gave for RootsTech 2025, which you can view for free.

1. When did this state become a state?

Was it one of the original Thirteen Colonies, or was it a much later addition? Was it previously part of any other territories? These answers affect not just the state’s history, but also what records were created.

2. When did vital records begin?

As we’ve discussed in this article, states adopted vital record-keeping at different times.

3. What privacy restrictions are in place?

Most states restrict more-recent vital records: birth records less than 100 years old, marriage records less than 50 years old, and death records less than 25 or 50 years old (for example).

4. Did the state take its own censuses?

If they exist, state census records are typically held by the respective state archive.

5. Was it public-land or state-land?

See the US Land Records section of this article for more on why this distinction is important.

This guide has only scratched the surface of what you can learn about your US ancestors. Through studying history and record-keeping practices, you can successfully trace your star-spangled family members—from the mountains, to the prairies, to the oceans white with foam.

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the July/August 2025 issue of Family Tree Magazine.